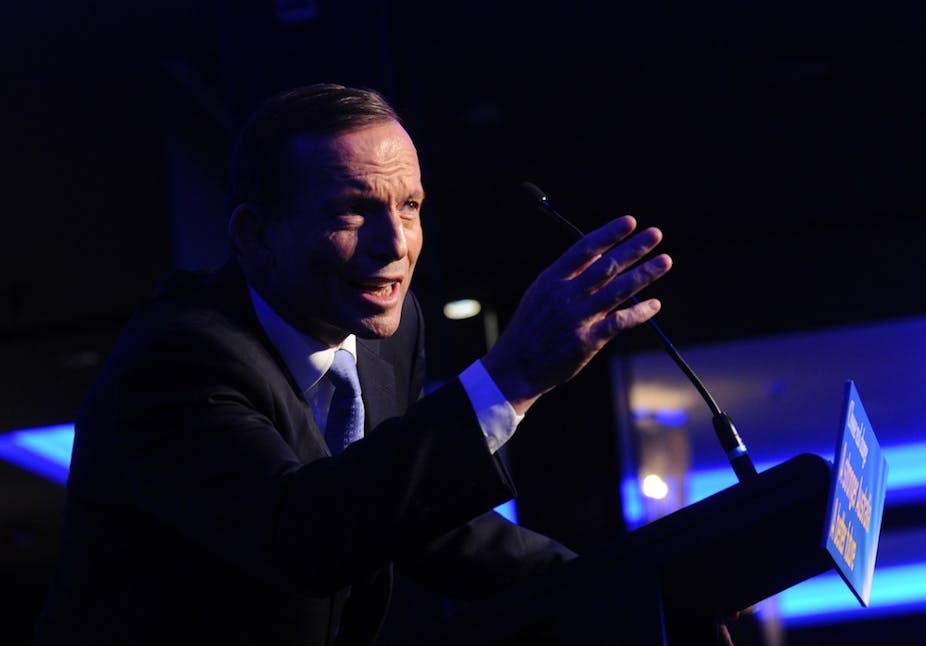

There has been much, and justified, criticism, of Tony Abbott’s decision to conceal the costings of his policies until two days before the election, when the electronic media blackout will be in place.

There’s an obvious risk that politically unappealing cuts are being saved until the last minute. But the most frightening possibility for an Abbott government is already in plain view: the promise to appoint a Commission of Audit. This has become standard operating procedure for an incoming Liberal National Party government, and the outcome is entirely predictable.

Over at least a dozen such Commissions, the script has never varied. The Commission will announce a discovery that the public finances are far worse than the outgoing Labor government admitted, and will advise the government to ditch many of its election promises.

Promises, promises

The abandoned promises won’t include handouts to business or favoured political groups - the necessary cuts will focus on health, education and payments to the poor and disadvantaged.

Of course, Abbott has promised not to cut these areas. But the political tradition of the LNP is that a Commission of Audit report trumps all such promises.

In the lead-up to the 1996 election, John Howard was asked directly whether he would stick to his promises regardless of the Budget’s state. But, with the aid of the Commission of Audit set up by Peter Costello, Howard invented the category of ‘core’ promises, which would be kept. The public was left to infer that everything else was ‘non-core’.

More recently, campaigning in Queensland, Campbell Newman promised public servants they had nothing to fear from an LNP government. When he took office, he turned to Costello to perform the inevitable Commission of Audit, which varied only marginally from the 1996 version Costello himself had commissioned.

Newman invented his own variation on the core/non-core distinction, claiming that he had meant his promise to apply only to ‘frontline’ workers. When the sackings extended to nurses and teachers, he clarified further, saying that he meant ‘frontline services’, not the workers who were supposed to deliver them.

It’s possible that the politics will prove too difficult for Abbott, as happened to Ted Baillieu. By the time his Commission of Audit report was ready, with its recommendations of radical privatisations, Baillieu was already on the way out and the report was too politically toxic to be released.

But that’s only likely in the event of a razor-thin majority, the outcome most voters would like least.

A question of scale

What effect would arise from the scale of cuts that the Commission of Audit typically proposes? The cuts introduced after the 1996 election were on the scale of 1-2% of GDP, equivalent to $15-30 billion today.

In the context of a weakening economy, as may well be the case, public sector cuts have a ‘multiplier’ effect, reducing activity by more than the amount of the original cut. The International Monetary Fund has recently estimated the multiplier at around 1.5, so that a 1-2% cut in public spending would generate a cut of 1.5-3% in economic activity, enough to turn a slowdown into a recession.

In terms of employment, the standard estimate, called Okun’s Law by economists, is that each percentage point reduction in GDP increases the unemployment rate by 0.5%, and reduces employment by about the same amount. In the worst case of a 3% decline, it might imply a 1.5 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate.

This is consistent with the experience in Queensland, where employment has declined, relative to trend, by more than the amount of Newman’s cuts.

Under normal circumstances, monetary policy could be relaxed to offset the effects of such fiscal austerity. But with the cash rate down to 2.5%, the Reserve Bank doesn’t have much room to move. The RBA would be very reluctant to cut rates to zero, at which point the only option would be the kind of quantitative easing that the US Federal Reserve implemented with only limited success.

Of course, it is possible that the Commission of Audit’s inevitable recommendations for massive cuts will be ignored and that an Abbott government will make no cuts beyond those to be announced on election eve.

As Winnie the Pooh’s gloomy companion, Eeyore, said in a similar situation: “That’s what would be so interesting. Not being quite sure till afterwards.”