In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

Every so often a woman takes up arms to lead a spirited struggle against invaders and occupiers of her homeland. Such women usually wind up dead at an early age, but they capture the imagination. The most famous example in British history is Boudica, aka Boedicea; in French history, it is Joan of Arc.

The Taiwanese revolutionary Hsieh Hsüeh-hung (1901-1970)is such a figure, although like most aspects of Taiwan’s history her significance is contested. Born in Taiwan, buried in Beijing, Hsieh was a communist and also an advocate of Taiwanese self-determination. In the history of world communism she is noted for being one of the founders of the Taiwanese Communist Party, established in 1928.

In the annals of the Taiwan independence movement, Hsieh has emerged as a heroine of the 1947 uprising, now the subject of an annual commemoration held in Taiwan in 28 February. In 1948 she founded the Taiwan Democratic Self-Government Alliance.

Hsieh Hsüeh-hung’s fate – in life and in death – was determined by the shifts in attitude towards Taiwanese independence on the part of ruling powers, and by the status of its local left-wing movements. To some degree, she is not so much a woman hidden in history as one rendered visible by it.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Théroigne de Méricourt, feminist revolutionary

Blood on the snow

Hsieh was a child of the Japanese empire. In 1894, seven years before her birth, Japan defeated China in a short war at sea, afterwards demanding Taiwan as part of the post-war settlement. It was to be the sovereign power in the island for the next half-century.

Hsieh’s parents were immigrants from Fujian province, the most common source of settlers in Taiwan. The family was poor. Hsieh was sent into service in a Japanese family at the age of eight. At 12, she was sold into a shopkeeper’s family to be raised as their daughter-in-law.

In an early show of feistiness, she ran away when in her teens, finding work initially in a Japanese sugar factory in Tainan and later, in her home-town of Chang-hua, as a representative for Singer sewing machines. As an extremely young person, she was exposed to the impact of international capitalism on her home turf, and to extremes of social inequality.

To these experiences, she added a growing political awareness. In Chang-hua she formed a relationship with a merchant named Chang Shu-min, to whom she was married for some years. The couple lived for around three years in Japan, where she began to acquire an education, learning to read and write in both Japanese and Chinese. Both there and back in Taiwan she came in contact with politically progressive organisations.

In April 1919, she paid her first visit to the Chinese mainland, staying in Qingdao, which at that time was about to be transferred from German to Japanese control under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, sparking the radicalising May Fourth Movement in China.

When she returned in 1925 it was to Shanghai, where she enrolled in Shanghai University – more like a cadre training school than an academy and dominated by Communist Party members. Together with fellow-Taiwanese Lin Mushu she was there recommended for acceptance at the Far Eastern Toilers’ University in Moscow, where they were groomed to set up the Taiwanese Communist Party.

Read more: Small but mighty: why Taiwan matters to Australia

The Taiwanese Communist Party was formally established on 5 April 1928. Its charter was the Taiwanese as a people or nation (minzu), and its slogan was “long live Taiwan independence.” The Chinese Communist Party early on took a similar view. In Mao’s stated opinion (circa 1936), Taiwan’s relationship to China was comparable to Korea’s. For Hsieh, there was no contradiction between the fight for socialism and the fight for Taiwan’s independence.

If being Taiwanese was one driving force in her political life, being a woman was another. At birth she was registered with the name A-nü, or “girlie,” not really a name at all.

From this assigned anonymity she became a vivid presence in history under the name “Hsüeh-hung”, meaning “the snow turns red”. She took the name, it is said, after seeing a worker’s blood spattered on the snow in Qingdao.

As a communist cadre, she was active in peasant and worker associations, but she took a rather independent view of the position of women in Taiwan. In 1930, she pointed to women’s emancipation movements in the Western bourgeoisie as worthy of emulation by Taiwanese women, with equal participation in political life among the goals. It is easy to see how in later years such views would land her in trouble with the Chinese Communist Party.

A born oppositionist

The 1920s were the decade of Hsieh’s political formation. Thereafter till her death in 1970 she was in conflict with three different regimes. To her cost, she was a born oppositionist.

The first of these regimes was the Japanese colonial government in Taiwan, the target of all political opposition movements in the island. In the context of a rising fascism in the Japanese home islands, the authorities conducted a sweep of Taiwan’s communist activists in 1931. This destroyed the Taiwanese party. Arrested, imprisoned, and subsequently sentenced on charges of threats to public security, Hsieh spent the next nine years in jail.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Hop Lin Jong, a Chinese immigrant in the early days of White Australia

The Japanese were replaced in 1945 by China’s Nationalist Party, which established a heavy-handed administration on the island, thoroughly alienating the locals. On 27 February 1947 a conflict between tax agents and a cigarette dealer met with protests. A brutal crackdown on 28 February led to an island-wide uprising that was eventually suppressed with great violence.

The insurgency unfolded in various ways across the island. In Taichung, near to her hometown on the central west coat, Hsieh, a known activist and political organiser, chaired a protest rally calling for self-government and played a key role in dismantling Nationalist Party authority in the city.

Taichung’s few days of independence are associated with three principles set down by her: protect mainlanders; protect public property; place weapons “in the hands of the people”.

Her name is also connected with the formation of the Twenty-Seventh Militia Corps, an armed force of 4,000 men meant to provide organised defence against the Nationalist forces. Between the things she actually did and the things she was blamed for doing, a legend grew up around her. With the collapse of the resistance on 9 May, a price was put on her head, and she fled the island.

The last part of Hsieh’s life, a period of more than 20 years, was passed entirely on the mainland, where unaccountably she found herself in conflict with yet a third regime, the Chinese Communist Party. Present with other communist leaders at the declaration of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, she was appointed to a number of official positions in the early 1950s, including chair of the Taiwan Democratic Self-Government Alliance.

The honeymoon was short-lived. She modified her position on Taiwanese independence to accommodate new political realities in the region, but never quite to the Party’s satisfaction. In 1952 she was attacked for lack of humility before the Party and for murky political thinking in relation to Taiwan.

In 1957 she was attacked again, and declared a “rightist”, losing her positions and her party membership. In the Cultural Revolution, she was attacked once more, this time physically. A photo provided to her biographer, now widely published on the internet, shows her in the hands of Red Guards in 1968. She died in Beijing in 1970, of lung cancer.

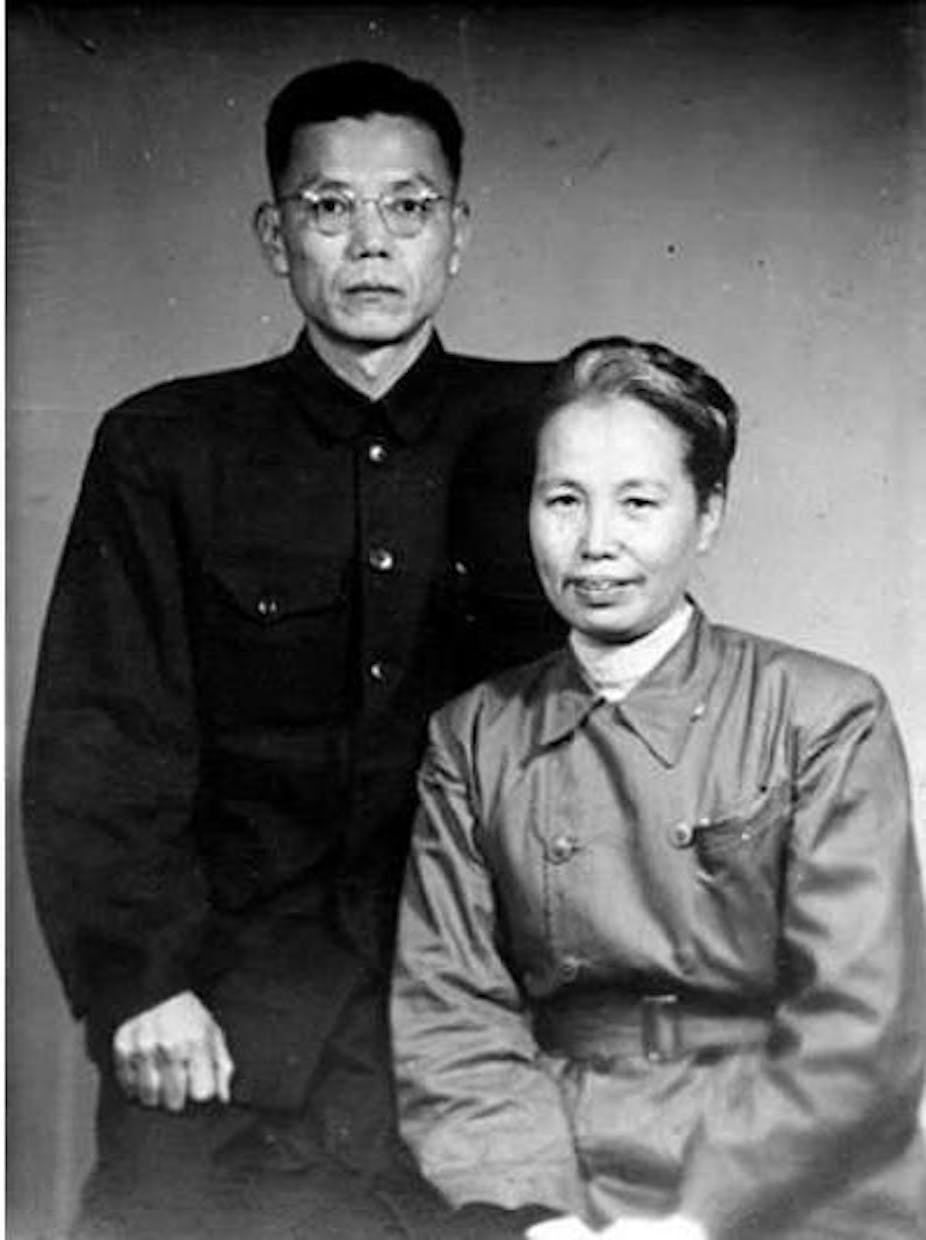

Emotionally, Hsieh shared most of her life and her mission with fellow-Taiwanese Yang K’o-huang, who was imprisoned with her in 1931, worked with her in a small business during the war years, and accompanied her to the mainland. The couple were never legally married: Yang had another family. But in the People’s Republic of China they lived together through the few good years and the many bad until her death. Her final words to him were that he should maintain the struggle: “the final victory will go to the people of Taiwan.”

In 1986, the Party decided to rehabilitate Hsieh. A short biographical statement written for the rehabilitation formalities included mention of her “deviations and errors” but conceded that she had “opposed invasion by outsiders” and had shown a spirit of struggle for “the realisation of the unification of the ancestral land.”

Left unchallenged, the rehabilitation statement might have defined her legacy. In 1991, however, a biography of her appeared in Taiwan. The author, long-time political dissident Chen Fang-ming, offered readers a portrait of Hsieh as a life-long champion of Taiwanese self-determination, whose tenacity and courage in face of political persecution put male political actors of her generation to shame. Widely read and influential, this biography effectively reclaimed Hsieh for Taiwan.