Australians are sending fewer letters, but what we do write packs a punch, both in our own time and for future generations.

In a sombre corner of the Melbourne Museum, a glass cabinet tells the story of first world war digger Frank Roberts and his wife Ruby. Part of the museum’s WWI: Love and Sorrow exhibition, it contains a parcel’s cloth wrapping, a bootie, and a brief letter penned by Ruby in the imagined baby-talk of the daughter born after Frank’s departure for Europe:

Daddy dear this is my shoe. Can you put it on dear daddy I wonder? … Mummy and I want you home so badly.

Frank Roberts never received the letter. He had died at the battle of Mont Saint-Quentin just days before its writing. The parcel was returned to Ruby, who held onto it for the rest of her life, a memento of the final days when she could still believe in her husband’s survival.

The force of this letter, and of other missives exhibited around the country to mark a century since the first world war, stands in stark relief against our diminishing reliance on snail mail in Australia today.

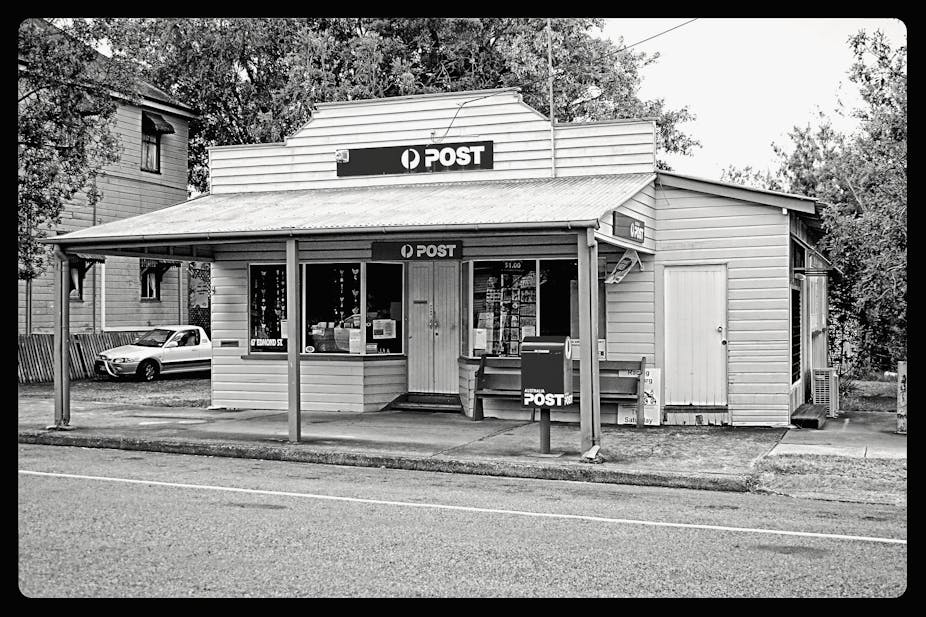

Last month, Australia Post announced that the volume of letters sent in Australia had declined by 8.2% during the second half of 2014, a nosedive contributing to the company’s forecast loss for this financial year, its first in more than three decades. Earlier this month, the federal government approved damage-control measures for our postal service, including raising stamp prices to A$1 and introducing a two-tier delivery model.

In an interview with the ABC on the day Australia Post’s figures were announced, Professor Stephen King, a Monash University economist and former commissioner with the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, made a blunt analysis of this data:

“The letter’s dead,” he said, estimating that in 10 or 20 years the standard letter as we know it will be gone. “It’s just that it refuses to lie down in its grave and be covered with soil.”

The interview focused on mail from business and government, which comprises the bulk of letters posted in Australia, with King advocating a smooth, equitable transition to a new era when the digital sphere takes care of our correspondence needs.

But while Australians may be sending fewer private letters than emails, any discussion limited to the utilitarian factors of service delivery and financial loss overlooks the letter’s unique, tactile role, particularly in its most intimate expressions.

This singularity hinges partly on the financial and temporal investment that letters demand, compared to cheaper and swifter SMS or email, an investment that elevates the recipient through either deference or love.

As the note sent by Ruby Roberts demonstrates, many letters do not die, and in fact survive beyond the human lifespan, embodying the moment when pen collided with paper. They are marked with tears, kisses and corrections, softened through reading and re-reading, spritzed with perfume and colonised by mould.

One of the most feted pieces of correspondence in Australian national mythology, Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie Letter, is framed by a narrative of its delivery, transcription and final donation to the State Library of Victoria in 2000.

Because of their physicality, letters are bread-and-butter for historians, communicating not only in their present but also to future generations.

Writer and activist Katharine Susannah Prichard recognised – and feared – the potential for endurance in her own correspondence when she consigned to flames many of her unfinished manuscripts prior to her death in 1969. Her son, Ric Throssell, described this methodical burning in his biography Wild Weeds and Windflowers:

She destroyed my father’s letters, her own father’s love letters to her mother, my letters from New Guinea, Moscow and Rio de Janeiro.

Whispers of more sinister conflagrations circulated during the 1970s and 1980s, when panic and misunderstanding about native title claims dominated public discussion. Australian National University historian Professor Tom Griffiths was a collector of manuscripts at the State Library of Victoria during the 1980s.

In a 2002 book chapter titled The Language of Conflict (published in Bain Attwood and SG Foster’s Frontier Conflict: The Australian Experience), he describes hearing stories of the destruction of the letters and diaries of early pastoralists who had documented massacres and dispossessions of local Aboriginal people.

The intention was not always to protect private land ownership. “One descendant of both settlers and Aborigines (and a supporter of Native Title) told me that he had once destroyed a station’s records ‘to protect people from an explosive political situation’ and ‘in the hope that it might clear the air for a fairer future’,” Professor Griffiths wrote.

For a historian, such erasure can seem dangerously close to the cultural vandalism of book burning. But paper as a historical source, for all its vulnerability to flood and fire, is also resilient in a way that technology is not.

The physical letter retains currency for as long as our language stays more or less the same. A digital file, by comparison, survives only for as long as we possess the software and hardware to decode it, and the accelerating speed of obsolescence is one of the archivist’s great challenges.

In the world of audio, the National Film and Sound Archive already stores a collection of obsolete audio equipment to enable historians and conservators to play historical files. Without the appropriate technology, future scholars may be as confounded by our digital data as early Egyptologists were by hieroglyphs.

The discipline of history adapts, of course. With at least partial management of technological obsolescence, the scholar of the 22nd century will be able to search our text messages, scan our tweets, fiddle our Facebook profiles, and trace our journeys via metadata. But she or he will lack the material clues to the writer’s mood or intent to help decipher ambiguous language, or might bemoan the absence of a postmark to locate the author in a particular place.

History is partially about framing enquiry into the past through the lens of the present. And the letter’s demise today will impose new and different limits on the questions those historians of the future might ask to better understand their own time.

The dominance of digital communication already shapes what we leave behind. But letters, far from being dead, will retain a place in our culture because they embody an intimacy and gravitas that digital communication cannot.

The best examples, as Katherine Susannah Prichard understood, will not acquiesce to being covered with soil.