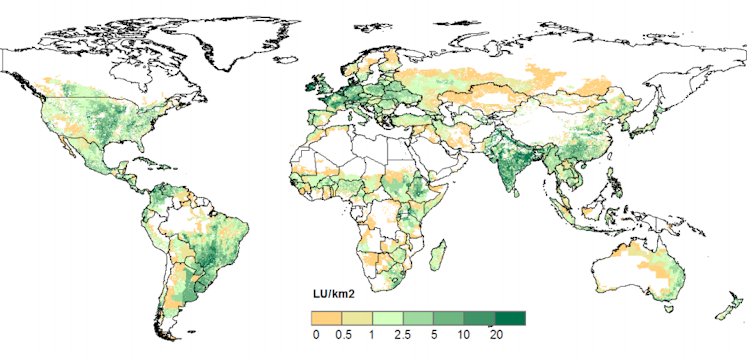

Raising livestock accounts for the largest single land-use on Earth. Cattle, sheep and goats, pigs and poultry occupy around 30% of the planet’s land area not covered in ice, generate 40% of the world’s agricultural GDP, provide livelihoods for 1.3 billion people, and nourishment for 800m people who would otherwise go without.

Despite this massive environmental, economic and social impact on the world, it is not a thoroughly studied industry. The results of a four-year livestock study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences compiles worldwide data that reveal the important role of livestock. While the study lays out the industry’s considerable greenhouse gas emissions, it also shows that demands to reduce numbers and meat consumption will come with unwanted consequences.

The study, a joint effort by researchers from the International Livestock Research Institute in Nairobi, Kenya, and the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria, examined 28 regions, eight livestock production systems, four animal species, and three products (milk, meat and eggs). The result is the most systematic analysis to date. Lead author Mario Herrero said: “Livestock are not well represented by accurate data, so we set out to do this with the idea to provide the standardised, coherent information necessary to allow others to do more sophisticated studies.”

Livestock by numbers

Based on data from 2000, the world produced 59m tonnes of beef, 11m tonnes of lamb, mutton and goat, 91m tonnes of pork, and 124m tonnes of poultry, together with 586m tonnes of milk.

Many studies have examined the environmental cost of livestock, for example the amount of grain or feed eaten by cattle, and the impact of that on direct food supply for humans. But of the 4.7 billion tonnes of feed eaten by livestock, almost half that, 2.3 billion tonnes, was grasses not fit for human consumption. This was followed by 1.3 billion tonnes of grain, and agricultural crop residues, silage, forage, and legumes make up the rest. There was substantial variation between different areas – in North America feed is largely grains, for example, while in the developing world agricultural leftovers and grasses are much more common.

Industrial scale production accounts for almost all pork and poultry produced in Europe, North America and China, while in South and Southeastern Asia up to three quarters is from small scale farmers. But nutrition varied widely between different production methods, for example feedlot operations, mixed crop and livestock, or grazing systems. Depending on the region, feed and production system used, the amount of meat produced could be less than the amount of feed fed to livestock to produce it. Feeding livestock for meat was up to five times less efficient than feeding them for milk.

The global picture is complex, and that’s why finding a solution is not easy, Herrero said. “There is no one size fits all policy. It is very hard to talk about the sector as a whole. It’s great that people want to solve the ‘big problems’, but the solutions that will work are at the community level, entirely dependent on the local circumstances.”

Cattle-based climate change

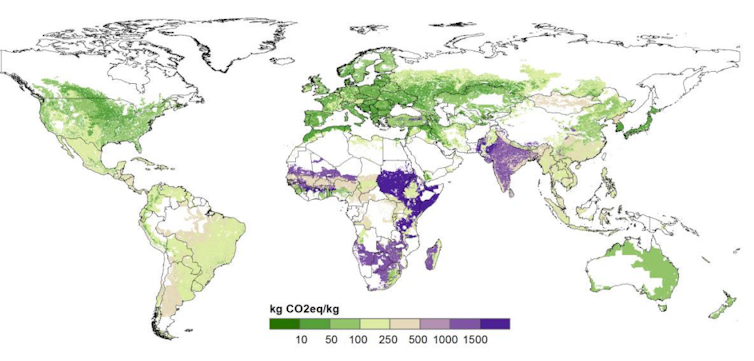

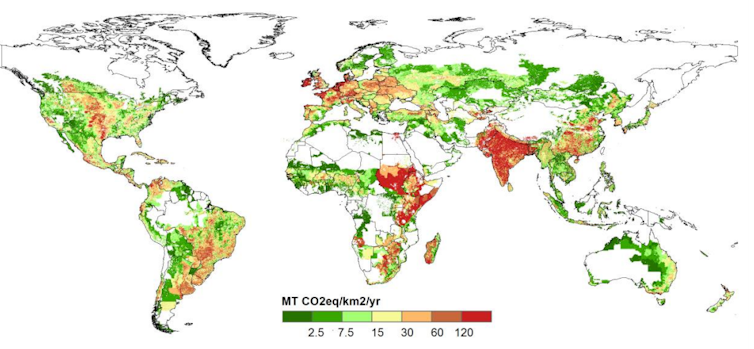

Greenhouse gas emissions of livestock is one area that has been researched. The study found non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions from livestock in 2000 were around 2.45 gigatonnes of CO2-equivalent, mainly methane from cattle, which accounted for 77%. The developing world accounts for two thirds of the world’s cattle emissions, and more than half of emissions from pigs and poultry. The highest regional emissions were from South Asia, Latin America, Europe and sub-Saharan Africa.

Besides emissions from the animals themselves and their manure, the enormous logistics behind industrialised cattle production also adds to carbon emissions. For example, where does the feed come from? “Provenance of feed matters a lot,” Herrero said. “If the Amazon has been cut down to grow soy beans fed to cattle, that carbon dioxide emissions of the changing land use will be tremendous compared to say, grain from the plains of Canada.”

Many have called for a reduction in the demand for meat and the numbers of livestock due to their associated greenhouse gas emissions. For example Tony Weis, Associate Professor at the University of Western Ontario and author of The Ecological Hoofprint said that industrial cattle farming “has no place in a sustainable society”, and that demand for meat, and the allure of meat as a marker of wealth, must be ended.

But Herrero said such claims don’t take into account the role livestock played in communities around the world. “Livestock are too important socially. They contribute 40% of global agricultural GDP and provide a livelihood for more than a billion people,” he said. “If you limit and decrease the number of livestock, the immediate question is: what are those people going to do? The economic repercussions are huge. The easy bit is to focus on the environmental impact, but the obvious solutions have tremendous social implications.”

He added: “That’s why analyses so far are unconvincing. We need to know what would be more sustainable levels of consumption, and how we are going to design systems that target change towards the groups we’re interested, mainly in the developed world, and not just hammer the world’s poor – whose meat consumption should probably actually increase to ensure they have proper nutrition.”

We need to ranch smarter

The implications of the study is that for millions of people, the cattle that underpin their livelihoods could be better fed, reader and managed much more efficiently. This would provide better use of resources, and a better rate of produce against carbon emissions. And, undoubtedly, it’s clear that we have to answer tough questions over how much meat and animal produce is sustainable, culturally appropriate, and ethical in a growing and resource-hungry world.

But interestingly, it also highlights the vital importance of grasslands. Despite feeding more than half the world’s cattle, grasslands are seen as expendable when land needs to be developed, or fenced-off entirely when seen as ecosystems to be protected. In some parts of the world grasslands face serious overgrazing, while in others they are the foundation of agriculture. “Grasslands are seen as a cheap option, a ‘free lunch’ with no opportunity cost”, said Herrero. “But there is no free lunch, and destroying grasslands risks losing pasture, soil quality, biodiversity of birds and insects, or affecting water supply and drainage, or carbon sequestration.”

There is no one-size-fits-all policy to fall back on. While we must intensify agriculture in order to feed more mouths, Herrero says, “there are social and developmental aspects to consider; we have to ask ourselves if efficiency is the only measure we wish to use.”