The National Curriculum Review was released this week, with the reviewers calling for a greater focus on “Western” literature in the English classroom.

As former high school and primary English teachers, we were left wondering what reviewers Kevin Donnelly and Ken Wiltshire think our students are reading in classrooms across the country, if not Western literature.

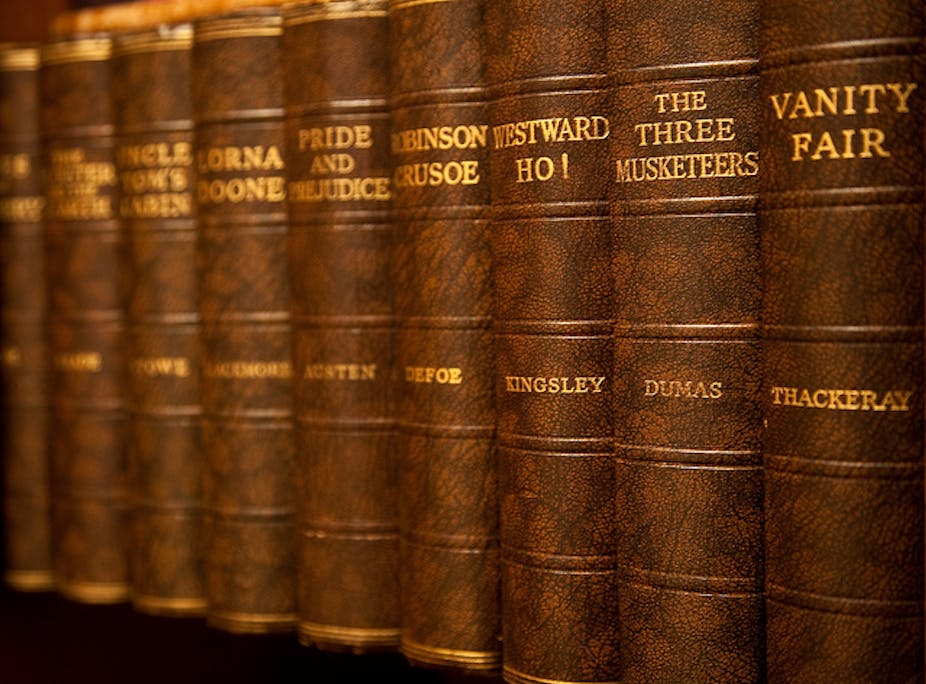

What exactly is “Western” literature?

The call for an emphasis on Western literature is unsurprising, given in the past Donnelly has argued that

no amount of politically correct clap-trap about the importance of indigenous and Asian texts can erase the fact that central to English as a subject are those enduring literary works that are part of the Western tradition.

So what is the literary canon according to Donnelly? Alongside Shakespeare and Dickens, the Bible takes centre stage.

Students already engage with a broad range of Western canonical and contemporary texts, both from Australia and abroad.

For example, the NSW Curriculum suggests using texts from authors such as Dickens, Eliot, Hemingway, Kipling and Orwell in Years 7 to 10.

When Victorian Year 12 students study for the VCE, they are expected to engage with Western canon greats such as Shakespeare and Bronte.

Barry Spurr, a Poetry and Poetics Professor at The University of Sydney, was chosen to review literature in the English curriculum. Some of his recommendations have made it through to the final report, including a

greater emphasis on dealing with and introducing literature from the Western literary canon, especially poetry.

Spurr believes that an

over-emphasis on 20th- and 21st-century texts produces an unbalanced curriculum, and certainly not a rigorous one, with regard to the discipline at large.

He goes on to declare that:

the range of study must extend from Middle English lyrics and the works of Chaucer to the present, with acknowledgement and experience also of ancient texts from the classical world and of the Bible – sources that, through the centuries, have had an inestimable influence on the development of literature in English.

The reviewers endorse this position on page 159 of their report, claiming that:

knowledge of the Bible is vitally important for an appreciation of Western literature.

Donnelly has previously argued that we need the Bible in our schools, prompting the question whether the review is free of ideology.

Choosing quality literature in the English Classroom

Currently, there is no prescribed literature in the Australian Curriculum. In its advice on selecting literary texts, the curriculum authority (ACARA) explains:

Teachers and schools are best placed to make decisions about the selection of texts in their teaching and learning programs that address the content in the Australian Curriculum while also meeting the needs of the students in their classes.

The Australian Association for the Teaching of English submission to the review commended the current situation, where

schools have the professional freedom to implement the curriculum with texts that they assess as being suitable for their own student cohorts.

The submission made by the Primary English Teaching Association Australia also endorses the curriculum’s flexibility for teachers to have control over context-appropriate literature selection.

Calling for an emphasis on the Western literary canon makes the curriculum more, not less, prescriptive. This runs counter to the government’s rhetoric on school autonomy.

This kind of prescriptive approach to text selection is the focus of the so-called “culture wars” and has previously been focused on secondary schooling.

What is different in this review, and perhaps most troubling, is the suggestion that this “historical study of literature” should begin from the Foundation year, where memorising and reciting the texts will assist students in ingesting

the flavoursome vocabulary of the simplest Medieval lyrics and the inventive conceptions of traditional fairy stories, myths and legends.

It’s questionable whether reciting and memorising Medieval poetry is appropriate for six year olds.

A call for more literature and less imagination

While the current English curriculum is not perfect, there are some groundbreaking and innovative features that seem to have become lost in the tired fights about phonics, skills and ideological warfare. One of these is the intertwining of three strands of content - Language, Literature and Literacy.

The Australian Literacy Educators’ Association submission to the review commended the curriculum, saying:

The central place of literature in the English curriculum ensures learners are immersed in rich language and that excellent models of written language are used to inspire student writing.

However, the reviewers claim that:

during the early years to middle years of primary school, there should be less emphasis on children creating their own literature and more on becoming familiar with literary texts – both fiction and non-fiction – as exemplars of high-quality writing.

This begs the question whether the NAPLAN Writing Task will continue to be sat by Year 3 and 5 students. After all, the composition of narrative and persuasive texts is a clear example of children creating their own literature.

In his analysis, Spurr declares that:

the idea of pupils as ‘creators’ of literature in English needs to be kept firmly in check.

This position has been labelled by the South Australian English Teachers Association president, Alison Robertson, as “crazy”, with text comprehension and composition going hand-in-hand.

Teachers should be given the professional respect to understand the learning needs of their students and to select appropriate literature for inclusion in their English program. The curriculum already supports this.

Editor’s note: Both authors will be on hand for Author Q&A sessions today (October 16) – Eileen from 12:30 to 1:30pm and Stewart from 3 and 4pm AEDT. Post any questions about literature in the Australian curriculum in the comments below.