Speculation China may be seeking to lower the temperature in its fractious dealings with Australia appears to be premature.

This follows confirmation that Chinese customers have been advised to defer orders of Australian thermal and metallurgical coal.

On top of this, Australian cotton exporters have been advised exports will be cut next year, a blow to a business worth about $2 billion annually.

Australian mining giant BHP has received “deferment requests” for its coal shipments, according to the company’s chairman, Ken MacKenzie.

On the face of it, this is the most damaging trade reprisal by Beijing against what it perceives to be Australia’s hostile attitudes to it in tandem with its security partner, the United States.

It seems more than coincidental that just days after Australia took part in a meeting in Tokyo of the Quad (previously known as the Quadrilateral Strategic Dialogue and involving Japan, Australia, India and the US), China took such action.

To put this in perspective, China has targeted Australia’s third-largest export commodity to the Chinese market behind natural gas and iron ore.

Read more: It's hard to tell why China is targeting Australian wine. There are two possibilities

In 2018-19, Australia’s exports to China of thermal coal for power stations and metallurgical coal for steel-making reached A$14.1 billion.

The Quad session left no doubt about its purpose. It was squarely aimed at furthering a China containment strategy, and perhaps outlining an Asian NATO.

“Asian NATO” is the description Chinese propagandists apply to the Quad.

Australia finds itself in a grouping that includes a hawkish US Trump administration, a Japan that is understandably anxious about tensions in its own region, and an India that recently found itself in armed conflict with China on its Himalayan border.

In all of this big-power manoeuvring, Australia is the minnow. So it is more vulnerable to Chinese reprisals, trade and otherwise.

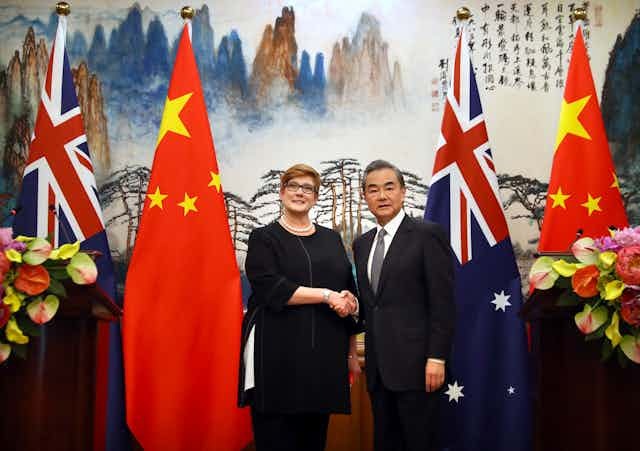

In a statement following the Quad, Foreign Minister Marise Payne avoided specific mention of China, but her message was clear. Australia was not hesitating to align itself with its Quad partners in confronting China. The statement said:

Ministers reiterated that states cannot assert maritime claims that are inconsistent with international law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

This was aimed at China’s refusal to accept a mediation ruling under UNCLOS that contradicts its territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Read more: China-Australia relations hit new low in spat over handling of coronavirus

However, even if Australia wanted to detach itself from a hard-edged American position on China, it would be difficult given the sort of rhetoric emanating from Washington.

For example, in a statement issued by US Secretary Mike Pompeo after his meeting with Payne, he said they had discussed “China’s malign activity in the region”.

Australia’s circumspect foreign minister would not have said this publicly.

The Pompeo remarks play into a Chinese narrative that Canberra is Washington’s appendage. In the conduct of its regional diplomacy in close co-ordination with the US, Australia tends not to challenge this narrative.

In an interview with Nikkei Asia, Pompeo said the Quad would enable participants to “build out a true security framework”. This will not have gone unnoticed in Beijing.

Nor would his description of the Quad as a “fabric” that could “counter the challenge that the Chinese Communist Party presents to all of us”.

Payne would not have gone this far.

In the wake of the Quad meeting, China’s strident mouthpiece, the Global Times, accused Canberra of using the gathering to “promote its own global status”. It asked:

[…] how much strength does Australia own with its limited economy and population? Moreover, if Canberra is bent on infuriating China, Australia will only face dire consequences.

This sort of bombast can be dismissed as simply another case of Beijing letting off steam at the expense of a country that is more vulnerable to Chinese pressures than other Quad members.

On the other hand, Australia’s vulnerability to trade penalties invites the question. What will come next? Will it be Australian wine exports to China worth more than A$1 billion a year, or will gas be the next target?

China has been picking off Australian exports over the past year as relations have soured.

It has slapped tariffs on barley, making the Australian commodity uncompetitive in the Chinese market. It has used non-tariff measures to stifle beef imports from five abattoirs. It has told Chinese students to look elsewhere for education opportunities. It has also discouraged Chinese tourists from visiting Australia.

The latter is moot, since the COVID-19 pandemic means inbound tourism has been stopped.

However, a series of trade reprisals should be deeply concerning for the Australian government as it wrestles with an economy hit hard by recession.

The last thing Australia needs in this environment is for its trading relationship with China to fall off a cliff.

The trade numbers underscore Australia’s unhealthy dependence on China.

In 2018-19, more than one-third, or A$134.7 billion worth, of Australia’s total merchandise exports went to China. On top of that Australia’s services business with China, mainly education, totalled A$18.5 billion.

In the first six months of this year, Australia’s exports to China neared 50% of total exports, mainly due to increased iron ore prices.

This level of business may be advantageous to Australia from a short-term perspective, but in the longer term such heavy reliance on a single market is highly undesirable.

It gives China the option of penalising Australia if Canberra’s policies do not correspond with Beijing’s wishes.

This is precisely what is happening now.

In the circumstances, it is hard to reach any other conclusion than that Beijing is targeting Australia as a means of conveying its displeasure that a regional united front appears to be forming to contain China’s ambitions.

In this context it is worth noting that despite a sometimes acrimonious “trade war” between the US and China, Beijing has, for the most part, refrained from penalising American business.

Of course, China exports far more to the US than it imports.

In the lead-up to the US election on November 3, Australia should be hoping for a Biden victory on the grounds that a more normal diplomatic environment will enable a reset of our relations with Beijing.

The alternative is further nasty surprises weighing on a critical trading relationship.