Migration is a top issue for some voters and candidates in the UK’s general election. The last 14 years of Conservative policy have introduced restrictive policies on both legal and irregular migration. And yet, net migration stands at 685,000, a near historic high.

Since the Conservatives entered office in 2010 and introduced a pledge to reduce net migration, these targets have been part of the political conversation. The general election campaign so far suggests not much has changed.

2010-2015: Net migration and the hostile environment

The 2010 general election put immigration front and centre of the political landscape for the next 14 years.

New Labour had previously pursued a managed migration system, which combined strict asylum policies with a more liberal approach to economic immigration. This included allowing citizens of the newly joined EU member states unfettered access to the UK labour market. This, along with a points-based system, had added 2.5 million foreign born workers to the UK population since 1997, transforming the country.

By 2010, the Conservative party had decided to place immigration at the centre of their campaign, with a simple pledge: reduce net migration (the number of people coming to the UK to live, minus the number leaving to move elsewhere) from hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands.

As the next 14 years showed, this was a gamble that never paid off. Net migration targets have never been reached but the pledge was too politically risky to abandon.

Want more election coverage from The Conversation’s academic experts? Over the coming weeks, we’ll bring you informed analysis of developments in the campaign and we’ll fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our new, weekly election newsletter, delivered every Friday throughout the campaign and beyond.

When the 2010 election delivered a Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition, the new government set out to achieve this target through restrictive policies across all streams of immigration.

Labour’s points-based system technically remained in place, but was curtailed with strict eligibility requirements. The coalition government restricted international student visas by limiting freedom to work during and after studies, restricting family dependants to only postgraduate students and making it harder to switch to work visas.

They also introduced more stringent English language requirements and got tough on alleged misuse of the student system (with suggestions of people entering Britain to work on a study visa), as well as family reunification, by cracking down on sham marriages.

But these reforms paled in significance compared to the efforts to reduce labour immigration. The government closed the tier 1 visa that allowed highly skilled migrants to seek work in the UK without a job offer. They made the main work visa for sponsored graduate employment only, increasing salary requirements and making permanent settlement much harder. The pinnacle of the reforms was introducing, for the first time in UK history, a limit on the number of work visas that could be issued (20,700 a year).

The defining immigration policy approach of this era was the hostile environment. Established by Theresa May in 2012 when she was home secretary, this approach was intended to make life “as difficult as possible” for irregular migrants (people coming to the UK without documentation or authorisation). But its policies have affected all non-citizens, and some citizens to this day.

Crystallised in two laws – the 2014 Immigration Act and 2016 Immigration Act – this set of policies added elements of immigration control to existing systems. For example, the right-to-rent scheme required landlords to check immigration status and prohibited irregular migrants from renting. They were also barred from obtaining driving licenses and opening bank accounts.

These policies had no effect on migration levels. They have, however, led to a spike in racial discrimination and, ultimately, the Windrush scandal which wrongly targeted British residents caught out by new documentation rules.

2015: Brexit and beyond

Despite this raft of restrictive policies, the Conservatives headed into the 2015 general election with net migration 75,000 higher than they inherited.

With limited government control over EU mobility and the electoral threat of anti-migrant, Eurosceptic Ukip on the rise, David Cameron pledged a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU. Concerns over immigration were a key, but not the only factor in the result.

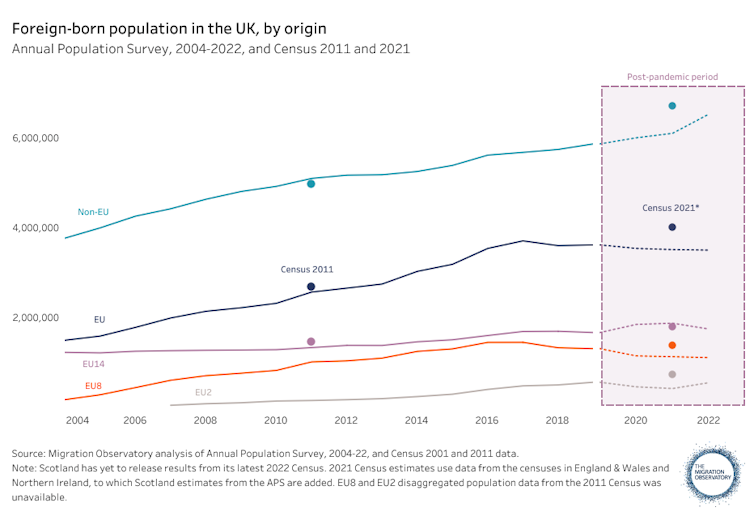

Once the UK voted to leave the EU, May (now prime minister) set about negotiating the terms of the deal. Early on in the process, she tied herself to ending free movement. This had an immediate impact on the labour market, which had long relied on EU citizens filling shortages in sectors like social care, hospitality, retail, agriculture and manufacturing. But EU citizens leaving the UK were quickly replaced by a rise in immigration from non-EU countries.

2019: the Johnson years to today

The newly elected Boris Johnson set out the government’s post-Brexit immigration policy, a vision of “global Britain”. This took the form of an “Australian-style points-based system”. The new system made no distinction between EU and non-EU citizens, but it was broadly the same as the one it replaced, with a new skilled worker visa. (Labour’s points-based system was never officially terminated, by this point it had become a points-based system in name only).

Johnson kept the goal of reducing net migration, but dropped a specific target number. And, recognising the labour shortages left by ending free movement, his government liberalised some aspects of economic immigration policy.

This involved reducing salary and skills thresholds, introducing new visas in public services and for startups, and bringing back post-study work visas and seasonal worker visas. But labour shortages continued, and the government backtracked on a number of policies – including a U-turn in 2021 to expand seasonal visas to poultry workers and HGV drivers to “save Christmas”.

Partly as a result of the increase in study and work visas, net migration reached its highest-ever level in 2022, and remained high in 2023. This was primarily due to increases in skilled workers in health and social care, international students (possibly due to opening the post-study work visa) and humanitarian visas introduced for people from Hong Kong and Ukraine.

With conflict in the Conservative party intensifying over immigration, the government brought in more dramatic restrictions in 2024. This included barring care workers and postgraduate international students from being able to bring their dependants, and increasing the salary threshold for skilled workers and family visas.

The immigration system as it has evolved over the last 14 years has been ad hoc, piecemeal and reactive to populist politics. It has been largely cut off from other policies affecting the labour market (especially in the NHS and social care), as well as the education and training of UK workers. An alarming consequence of this has been the levels of migrant worker exploitation in these sectors.

At the same time, the rhetoric on migration has become more polarising and toxic, and the goal of reducing net migration has persisted.