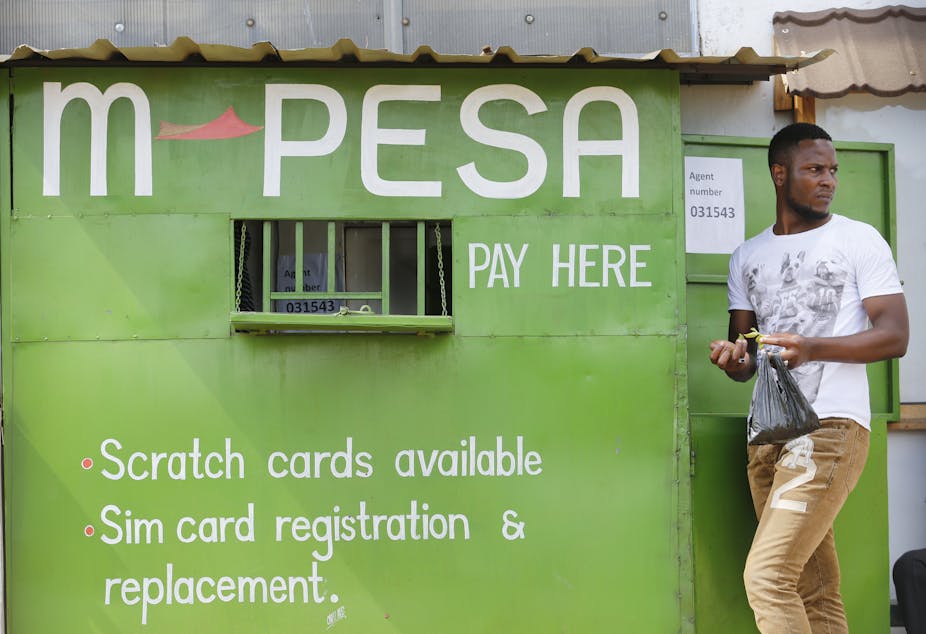

It started as a development project in Kenya designed to help poor rural entrepreneurs without bank accounts. Now M-Pesa, a phone-based money transfer service, has millions of users across the country.

So far in 2021, those customers have used M-Pesa (M is for mobile, and pesa is Swahili for money) to move over 580 billion Kenyan shillings (£3.8 billion) per month.

The service has come a long way since it was founded 14 years ago to enable the payment of micro loans. It quickly grew as a popular way to send money back home to dependants, and now supports a full banking service with bill-paying, savings and loan facilities, as well as a system that allows customers to complete transactions even when they lack sufficient funds.

For poor customers, the arrival of M-Pesa offered a way to take control of their lives. Women in rural villages could bypass patriarchal control of family finances to pay school fees and support small businesses.

Workers in cities could send money home quickly and cheaply. The key value of M-Pesa was that it served the needs of people who had previously been unable to access traditional banks. For those living precariously, it offered a route to freedom.

For our research we interviewed M-Pesa users in some of the poorest villages in western Kenya to understand what the service meant to them.

Their stories of deprivation and the effect of M-Pesa were then transcribed into poetic form to best express their feelings towards the service.

These suggest that a particular value of M-Pesa lay in freeing women from male financial control and supporting informal business relationships. Mothers could send money to daughters whenever they got a bit of money. They could stop husbands and brothers blowing the school fees on alcohol.

A 50-year-old woman customer said M-Pesa was: “Like drinking fresh water on a dusty afternoon.”

She added: “Poverty undresses you, weakens you, exposes you to every attack.”

A 48-year-old woman told us:

I have three men: my husband, my first two boys; all they do is eat, drink and sleep. Every morning they are looking for the best liquor. They are my burden, so I will carry it. I use M-Pesa. I send my daughter money in school.

A woman of 18 said:

I sent my cousin my number. She has not stopped sending money ever since, Sometimes in the middle of the night I receive a message. It’s money; very pleasant surprises, yes very pleasant. We can receive money. Save. And be safe from idle men.

One 41-year-old man reflected: “I have stopped thinking of M-Pesa as a technology. It’s become a part of me.”

Our research shows that M-Pesa has clearly improved the lives of many.

Money on the move

In April 2020, the South African company Vodacom, jointly with Kenya’s Safaricom, took total ownership of M-Pesa from the UK company Vodafone (which launched it with Safaricom), aiming for further geographical expansion and greater development of financial services.

We hope such ambitious levels of expansion do not end up transforming M-Pesa into a tool for more affluent users, rather than the people who fall outside of traditional financial frameworks. So as the operation grows and becomes more sophisticated (it launched an app for smartphones earlier this year), their services should remain within reach of those who only have access to more basic technology (only 25% of M-Pesa customers own a smartphone).

Unless that happens, M-Pesa’s original purpose may be sidelined, as it risks looking more and more like any other banking system, rather than a way of helping the poor.

Our concern is that those who cannot afford the latest technology simply get left behind. As M-Pesa (whose owners, Safaricom and Vodacom, declined to comment when we raised these issues) becomes increasingly commercialised with new apps, e-commerce sites and banking structures, there is a risk that its great value to the disenfranchised diminishes – and they become even poorer.