Facial reconstruction is best known as a forensic tool that can help identify human remains and reconnect them with families for burial or memorialisation. The technique has a potent claim on our imaginations.

These images are usually produced when other identification methods have failed. It’s usually a last resort with very high stakes. This is perhaps why, when forensic depictions lead to recognition in spite of their own technical limitations, it can feel like a miracle, providing an essential, often long-awaited, piece of an investigative puzzle.

Facial reconstruction becomes most culturally visible when it is applied to archaeological research. Depicting past people enables viewers to imagine them as individuals rather than specimens. The facial image becomes a powerful and complex medium, fostering connections between historical events and personal lifeways, and re-establishing a degree of personhood.

This research is facilitated by advances in imaging technologies, and benefits from interdisciplinary input. In turn, it creates new opportunities for the retrieval of previously unknown or suppressed knowledge that reshapes our understanding of the past.

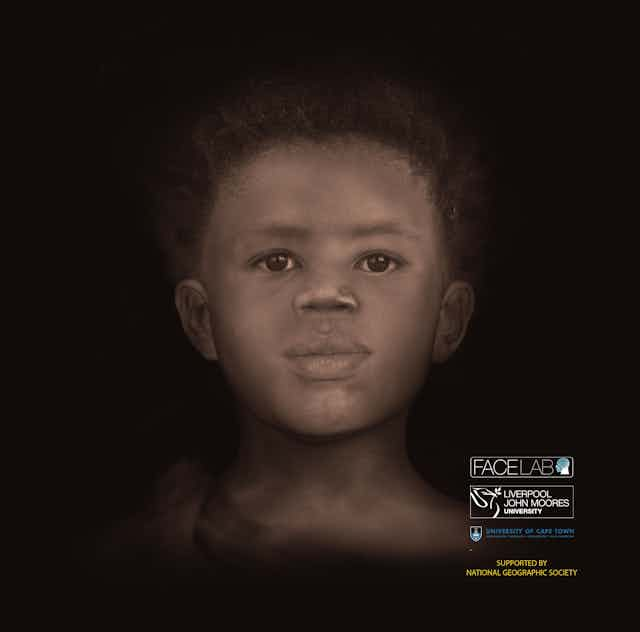

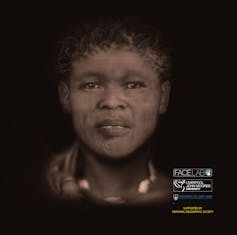

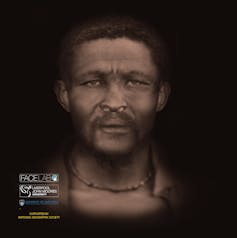

What has become known as the Sutherland Reburial project offers a unique opportunity to reflect on the objectives of recreating faces from skulls. The project involved creating facial depictions based on human remains unethically acquired by the University of Cape Town in the 1920s.

The project has become a platform to ventilate the unfinished business of human remains discovered from South Africa’s unpleasant past. It has also set a precedent for repatriation and restitution initiatives. The most critical is the involvement of direct descendants with links to the farm where the majority of these remains were exhumed, and their specific request to “see the faces” of their ancestors. Giving us their permission with their instruction, they collaborated in producing scientific knowledge for the benefit of the source community in Sutherland.

The project has also demonstrated how science, art and technology converge in contemporary facial reconstruction and depiction.

How it’s done

At the start of May 2019, the project was undertaken by Face Lab, recognised as an international leader in craniofacial research and analysis, with an entirely digital workflow.

Facial reconstruction interprets the details of the skull to recreate face shape through modelling of facial soft tissues, estimating the shape and size of facial features and using methods developed over a century of scientific and artistic collaboration.

Current methods have shown that shape can be accurately recreated with less than 2mm of error for approximately 70% of the facial surface.

The surface details of a face, known here as “texture”, are a matter of interpretation. Eye and hair colour, skin tone, wrinkles, scars and other marks, and some aspects of the ear cannot be reliably predicted from the skull alone. Genetic phenotyping is making some advances here, but not without significant controversy.

Yet these details are essential for creating a plausible face, so we must make a reasonable attempt, restricted by what can be justified by the available data.

In Face Lab, we refer to the final result as a “depiction” to distinguish between the process of recreating face shape – informed by anatomical standards that apply across all populations – and the highly interpretive process of adding surface details. The final depiction should employ visual strategies known to optimise recognition, but also infer ambiguity where necessary.

Our job is therefore to predict the “most likely” in-life appearance of an individual by attending as closely as possible to the specific, not the average. Producing the right sort of face, with the features in a certain proportional and spatial relationship to each other, determined by a skull’s own architecture, is what narrows the search for an unidentified victim in a forensic context.

Refining individualising detail – a gap between the upper teeth, prominent ears, a crooked nose or asymmetric eyes – increases the chances of successful recognition.

In the lab

Face Lab worked with 3D digital models of the Sutherland skulls produced from CT scans, which provided excellent surface detail along with internal information that refined feature prediction and allowed estimation of missing jawbones (mandibles). This was necessary for three individuals in this group.

Where bony fragments were missing or damaged, reassembly was a necessary first step. The more bone is absent, the more qualified the final result.

Face Lab employs a 3D modelling programme with a haptic (touch-sensitive) interface. This process non-destructively mimics a manual sculpting process, enabling optimal preservation of fragile or damaged bone by building up the soft tissues of the face in virtual clay. Rendering the various layers transparent to view the underlying skeletal structure at any time during the process enables continual evaluation.

Extensive visual research guided our final presentation choices for the Sutherland faces. This was supported by information from within the team, including ancient DNA which confirmed biological sex in some cases, as well as kinship and geographical origins.

We chose to present these people as they most likely would have appeared at their approximate age at death. The environment in which they lived and their likely lifestyle – harsh weather, basic diet and physical labour – would have affected their appearance. Older adults would have likely had more heavily wrinkled skin than contemporary people of the same chronological age.

Clothing was suggested based on contemporaneous archival photographs taken in the same broad geographical area. Adding a sepia tint introduced an element of colour in keeping with 19th century photographic techniques and visually situates them in the period in which the majority lived.

They are historical interpretations produced with forensic fealty.

Unnerving reality

Presenting the images to the families evoked complex emotions, from intense curiosity to guarded apprehension. The level of realism was clearly unnerving, but ultimately compelling.

The faces were ciphers for a process of recognition that was about being seen and heard.

In a place where indigenous histories are conspicuously absent, the Sutherland families believe that having these stories brought to life in a tangible and dignified way fosters meaningful connections between the past and present, and for future generations.

Local heritage practices in South Africa have not taken advantage of what these techniques can deliver. The Sutherland Project is one model of what opening up institutional processes and analyses to those affected by historical crimes might look like.

Informed by how humanitarian values might contribute to historical redress initiatives, the Sutherland project poses ethical questions that have specific local expression but are globally relevant.

The biographies this process was able to reconstruct, embodied in these eight faces, are highly specific. But they stand for the experiences of many others over many decades, who have been lost to history, but from whom we have a great deal left to learn.