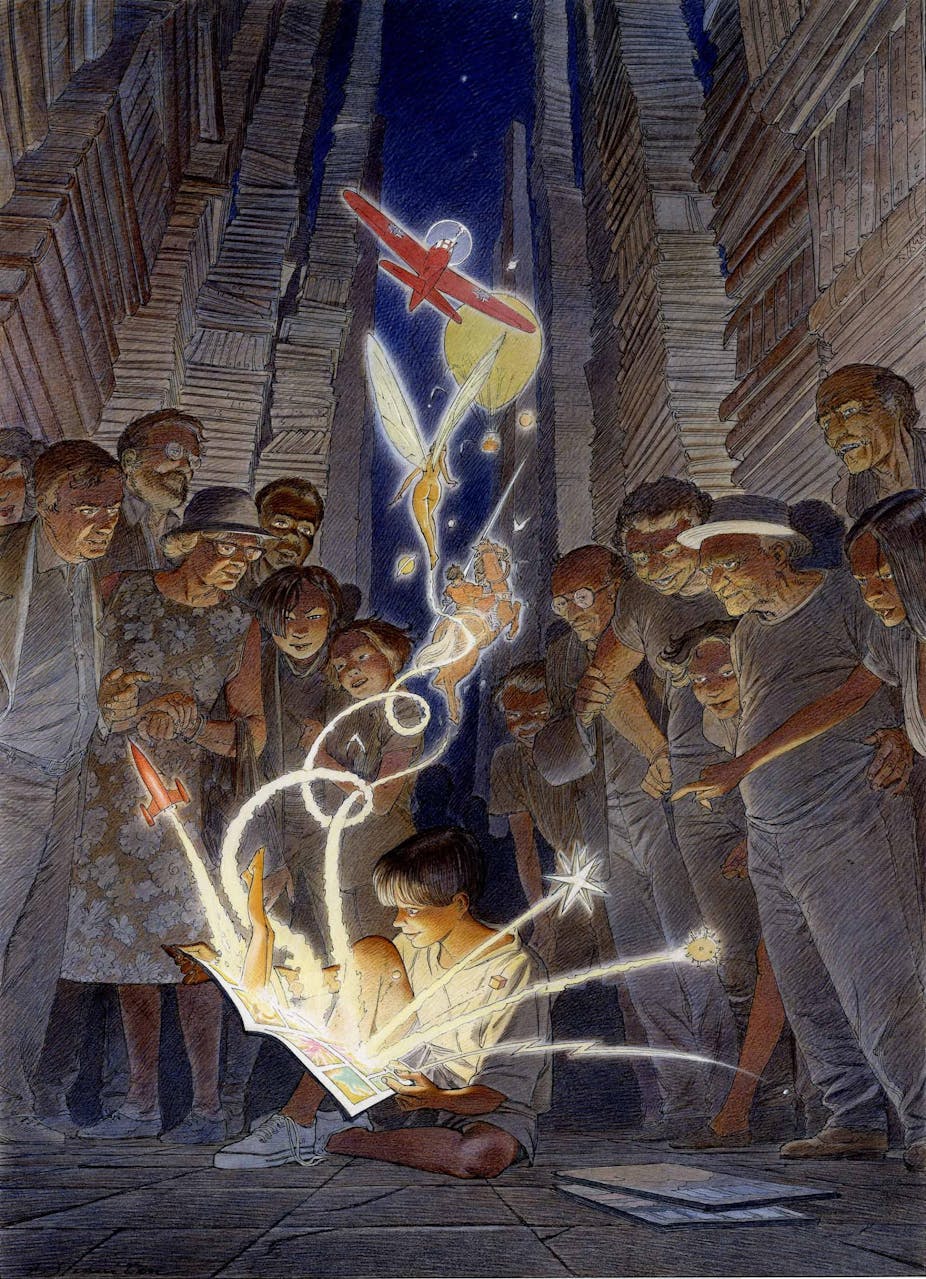

Traditionally, comic books have been aimed primarily at children – to such a degree that they are often identified with them. Regardless of the recent evolution of the genre, particularly given the growing popularity of more adult graphic novels, to me the link between comics and childhood continues to be very profound.

There are certain regressive aspects to our love of comics and “bandes dessinées” (or BD) – as they are known in French, my native language. For example, collectors often pay incredible prices for figurines and old editions. They also have a remarkable desire to keep alive mythical characters after the death of their creator: from Batman and Astroboy to Spirou and Blake and Mortimer, characters continue to be resuscitated, with varying degrees of success. It’s as if the readers who were comforted in their childhood by these heroes can’t bear to see them disappear.

This seems to be something particular to the medium of the comic book. Of course, we remember the novels that we loved during our childhood, but we don’t read and return to them as often as our favourite comics.

A thirst for innocence

It’s also possible to admire great works of literature, philosophy and art without the need to return to them compulsively or to spend thousands on first editions. But there is a kind of archaic drive behind our relationship with comics, an inconsolable nostalgia mixed with an irresistible desire to not completely grow up. We dismiss this phenomenon by talking about childishness. But it’s more about a thirst for innocence or permanence that we keep carrying around inside us, and which comics allow us to satisfy easily.

But of course, this direct link with childhood is only one aspect of graphic fiction. Comics have also been evolving.

In many modern comics since the 1970s, for example, the heroes are no longer invincible – they are affected by age or their own fragility. Comic book characters increasingly are caught in linear time, which affects and transforms them, just like it does every one of us. Links with others are made and remade, injuries cause real suffering, people, including the heroes themselves, die. They have abandoned the mythic to enter the romantic.

This new relationship with time is at the heart of many celebrated graphic novels, particularly the two volumes of the Pulitzer prize-winning Maus, which reimagines the Holocaust, casting mice as the Jews and cats as the Nazis. But Art Spiegelman’s masterpiece doesn’t just deal with the Holocaust and its survivors. It is concerned with a lot of other issues: the relationship between father and son, the difficulties of communication and of forgiveness. With the death of Vladek, the narrator’s father, in the middle of the story, memory changes function and gives a new sense to the work: mourning and history are inseparable.

In another way, Japanese manga such as My Father’s Journal or A Distant Neighborhood by Jirô Taniguchi pose similar questions. So too do the extraordinary biographical works accomplished by Emmanuel Guibert in The Photographer and Alan’s War. Mixing personal and universal elements, those stories are subtle and complex as the best novels.

A particularly striking example is proposed by Lint, one of the recent books produced by Chris Ware which describes the life of an ordinary man, from his birth to his last breath in 70 pages. The graphic and narrative style is codified to the extreme, far removed from any apparent realism. Ware’s designs are on the edge of a diagrammatic style. And yet, when we read this book – in which each of the years of Lint’s life is reduced to a single page – we are plunged into a story that deeply moves us.

This book moves us, not just because we identify with a character, as we might when watching a film, but because we identify with the medium itself. The pages of Chris Ware’s book evoke a mixture of emotions, primitive and childlike and sophisticated and adult at the same time, that appeal to a whole spectrum of experiences.

This highly sophisticated graphic novel can help us to understand how comic book art is connected with childhood, even in its most subtle and modern evolutions.

Drawing donkeys

The simplicity of comic books is another key feature. Around 1840, Rodolphe Töpffer, inventor and first theorist of the comic book, had already started questioning the manner in which a child recognises a donkey illustrated in a linear drawing. When a donkey is represented in a picture in the middle of the countryside accompanied by a play of light and shadow, a young child can’t always immediately identify it. But if the donkey is suggested only by a few lines, the child doesn’t hesitate to recognise it. Even if a tree trunk is placed in front of the donkey in this simple linear drawing, so that only a few fragments of it are left, the child still sees it for what it is.

This tells us something about the specific way we perceive caricatures, such as those in comic books. When it’s a light touch design, a caricature fixes an image in our minds which cannot be erased, as if it has unveiled somebody’s true character. Through this we can see another essential quality of the comic book: its ability to stick in our memory.

In the midst of the flux of images and art surrounding us, comic books have a special and unforgettable place. They have a remarkable capacity to prolong the life of images well beyond the time of reading. The most remarkable sequences of images continue to live with us, accompanying us for years.

In this regard, the nearest thing to the comic book is perhaps the song. I don’t think there is any song that we fall in love with immediately: we have to listen to it again and again – sometimes obsessively – until it has infiltrated us and accompanies us in our daily life. To me, comics are similar to this: they live where we dream to live. There is something unique and profound here, comic books are a privileged way of renewing the buried emotions of our childhood.

It’s Asterix versus Tintin in a Clash of the Toon Titans for the Lakes International Comic Art Festival’s opening night (Friday, October 14). The Festival team have joined forces with Lancaster University to stage a battle of comic superstars. Putting the case for Tintin is Lancaster University’s new professor in Graphic Fiction and Comic Art, Benoît Peeters. Asterix is being championed by Peter Kessler, BAFTA award-winning producer and author of The Complete Guide to Asterix.