How do we speak trauma? We know from medicine that people embody trauma, beyond words. It shows up in our hearts and our blood pressure, our dreams and our nightmares; we pass it onto our children, and we work it through in arts, spirituality, counselling.

My work has focused on a burning question in South Africa: how did women survive, care for others, and live through the many traumas of apartheid? I was interested in looking for ways to dismantle the polished narratives that circulate and are so often taken as the norm. These narratives speak of healing and forgiveness and of democracy and buried past.

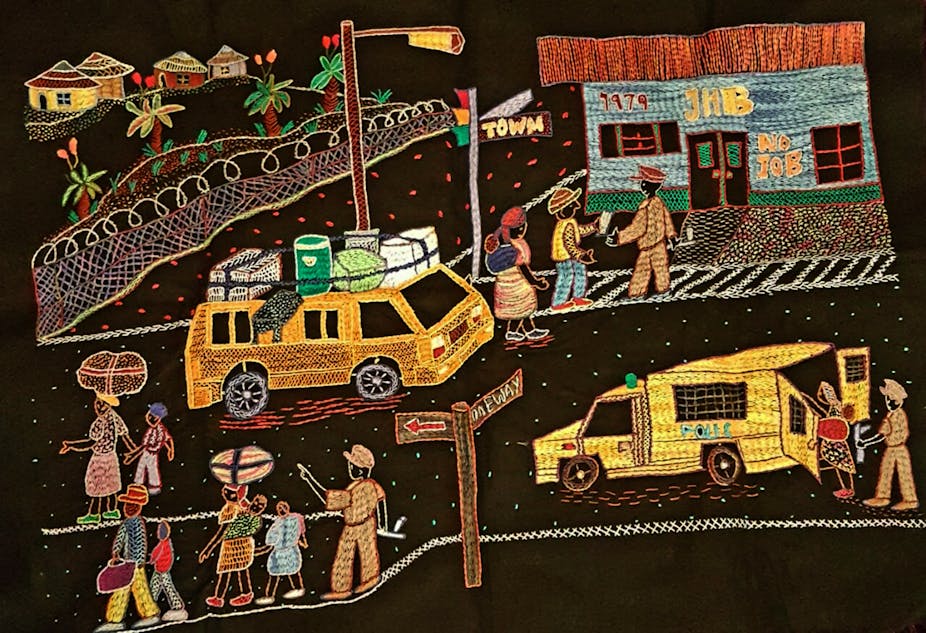

We know the “crisis” was not singular. Under the apartheid regime, many black women lived in underdeveloped areas with no jobs. Many of these women had husbands who lived and worked far away from home. Black women had limited rights, and even though they were allowed to work (under very restrictive conditions), they could be dismissed at any time and with no pay.

These women faced unequal pay and restricted access to the white neighbourhoods where they worked. Back home, they had children and elders to care for. Gender inequality was very apparent during this period as women were underpaid regardless of what job they did. Most of the women left their households for long hours every day to work in the white neighbourhoods.

And yet, with oppression comes resistance. Many of these women got involved in organised marches and demonstrated against the laws that were imposed upon them.

I studied the experiences of black women who grew up during apartheid and used the artistic form of embroidery to break the “culture of silence” that so many of them were accustomed to.

The study revealed that creating the opportunity for people to tell their own stories and make meaning of their life experiences is a step towards emancipation. It helps in reducing the unequal power relationships that exist when people are spoken for. Using embroideries to narrate personal experiences and the injustices they constantly face, the women show how art can be a form of social transformation.

A stitch to salve the pain

Many women continue to live in poverty, earn minimum salaries, and suffer intimate partner violence. These persistent challenges of the past and the present lead to women having to carry unspoken traumas. The traumas they describe should not be seen as isolated events for they occurred and continue to occur within their daily lives.

Breaking the silence is an important starting point. Embroideries in particular can show the complex and interwoven nature in which lives intersect.

Beyond making visually appealing artwork, needlework has always been a useful tool to tell difficult or unspeakable stories. Through depicting their lived experiences of gender trauma, women can have an outlet for their pain. While their embroideries serve as a canvas for the outpouring of pain, loss and trauma, their work also tells stories of hope, resilience and resistance.

The women wove together experiences of the past and the present. The art told complicated stories of what it means to be a woman living in South Africa. Through their artistic visual work, the women journeyed back in time to make meaning of the past and present.

The apartheid system systematically incapacitated people’s ability to imagine their lives differently. For example, they were denied the opportunity to receive good quality education. But the women’s embroideries highlight narratives of resilience and resistance, thereby refuting the popular narratives of equating oppression with damage.

Embroidery offers the opportunity to highlight structural violence and inequalities that have a direct impact on people’s everyday encounters. Embroidery further offers space to those who embody the injustices to create knowledge, produce and lay out their experiences onto the cloth. This becomes multilayered with stories of pain, anger, resilience, resistance, hope, love and desire.

What we know and what we need to do

We know women carried the pain for families – as bread winners, as abandoned wives, as daughters, mothers and aunties. We know that they endured the hardships of apartheid and economic troubles, structural violence of “pass laws” and violence at the hands of intimates.

We know women resisted in ways public and private, large and small. We know that state programmes to “help” women are not as effective as opportunities for self-determination, resources to be driven by the women for the women.

And we know as social scientists is that expression through art forms – visual methods – may reveal experiences that will not be spoken in an interview or a focus group.

As the women continue to journey towards true liberation, social justice and freedom, they do so by highlighting the collectiveness of their experiences and suffering. Looked at collectively, their embroideries, while focusing on individual experiences, provide a chorus that shows connections and breaks historical silences.

By making embroideries, women move beyond and challenge categories and labels of “being vulnerable” or being perceived as “marginalised”. More communities could use art forms to confront gendered societal challenges. Individual and collective artistic expression can play a role in the attainment of a just society – and it deserve more attention.