Key Democrats are proposing ways to make the rich pay more taxes.

I believe one of the most promising is Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax. There’s only one snag: It is arguably unconstitutional.

Under her proposal, households worth more than US$50 million – about 75,000 families – would pay a rate of 2 percent a year on assets. Above that the tax would be 3 percent. As opposed to an income tax, this would be levied on things like real estate, cars and stocks.

As a tax scholar interested in economic inequality, I can see the appeal of a wealth tax. The U.S. is growing increasingly unequal, and the best way to reverse that trend is by taxing wealth.

Nevertheless, a clause in the Constitution forbids direct taxes on wealth like the one proposed by Sen. Warren. The reason lies in the compromises our Founding Fathers made over slavery.

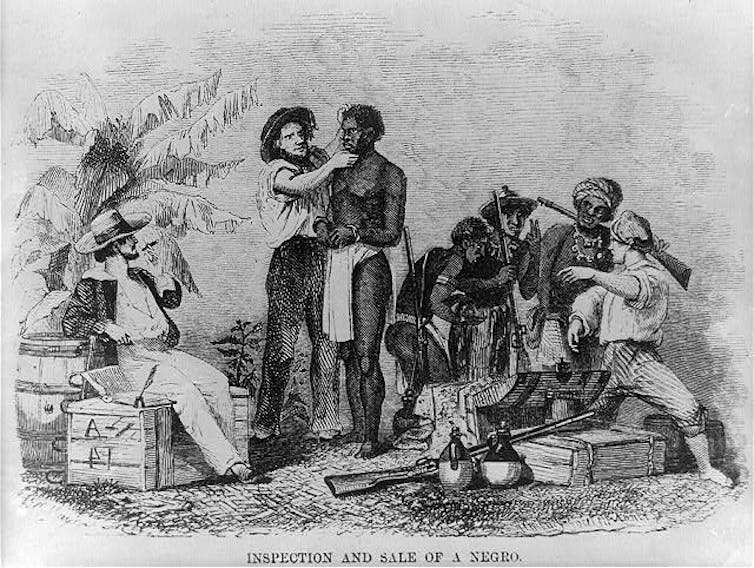

Slavery and the Constitution

The specific culprit is Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, also known as the Apportionment Clause.

“Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States … according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons … three fifths of all other Persons.”

Written by delegates at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, this passage contains two compromises deeply rooted in Southerners’ fear that their Northern neighbors would politically overwhelm them to the detriment of legal slavery.

One of them is likely familiar to most Americans: the three-fifths compromise, which counted slaves as a fraction of a person for determining representation for each state. This addressed Southern states’ small population problem.

The slaveholding states had relatively few people spread across lots of land, compared with the North’s large populations living in relative density. In addition, while Southern states had many slaves, Northern ones had very few.

Northern delegates didn’t want to tally slaves for the purposes of representation in the House, but, without them in the count, the South’s already small population shrunk by more than a third.

So to protect the South from perpetual political minority status, delegates reached the three-fifths compromise. The three-fifths compromise was abolished by the 14th Amendment.

Why Warren’s tax is unconstitutional

The second compromise was apportionment. This is what makes Warren’s wealth tax unconstitutional in my view.

Even with the three-fifths compromise, Northern states had a proportional advantage in the House of Representatives that would make it easy to pass taxes targeting the South while leaving the North relatively unscathed, such as taxes on land and slaves.

To avoid regionally focused taxes, the delegates agreed that “direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several states.”

A direct tax is a tax on a thing, like wealth and income. An indirect tax is a tax on a transaction of a thing, like the taxes on the sales of estates, property and most goods.

This means that the amount of a direct tax paid per person in one state must be the same per person in every other state. So if a tax costs Alabama $1,000 per person, the impact on Minnesota and California must be the same. It doesn’t matter who actually pays the tax, so long as the per capita cost for each citizen is the same across every state.

For example, imagine a country with two states, each with 10 acres of land. But one state has five people and the second contains 25. The federal government imposes a wealth tax of $5 per acre.

Both states send $50 to the federal government. The per capita cost of the tax, however, is $10 in one state and $2 in the other. That result violates apportionment.

That’s the problem I see with Warren’s wealth tax. It is a direct tax without apportionment. Because wealth is unevenly distributed across the population and across states, the total tax paid in each state cannot produce an equal per capita tax.

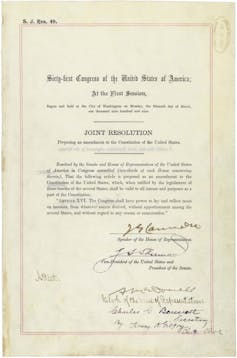

You may protest that the income tax is a direct tax and clearly not apportioned. Indeed, there was no regular income tax until Congress passed the 16th Amendment in 1913, which gave the federal government the “power to lay and collect taxes on incomes … without apportionment.” Prior to that, Congress for short periods levied taxes on incomes to pay for the Civil War, but the Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional in 1895.

Constitution’s last remnant of slavery

The solution to Warren’s problem is to expand the 16th Amendment to allow a federal tax on wealth.

But doing so is difficult to achieve. Congress must pass an amendment with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House and the Senate, followed by passage by three-fourths of the state legislatures.

I believe the wealth tax is worth the trouble, however, because it addresses the core of American inequality: wealth concentration. The richest 1 percent now own more wealth in the United States than at any time in the last half century. So long as income is taxed but wealth is protected, the gap between the ultra rich and the rest of us will grow.

One thing that stands in the way is a 200-year-old provision meant to support slavery by increasing slaveholders’ power.

In the 21st century, what senator, representative or state legislator wants to stake his or her reputation by standing in support of the last remnant of slavery left in the U.S. Constitution?