Under editor Esmé Fenston, by the end of the 1950s, the Australian Women’s Weekly was selling over 805,000 copies a week. More than half of all Australian women read the magazine.

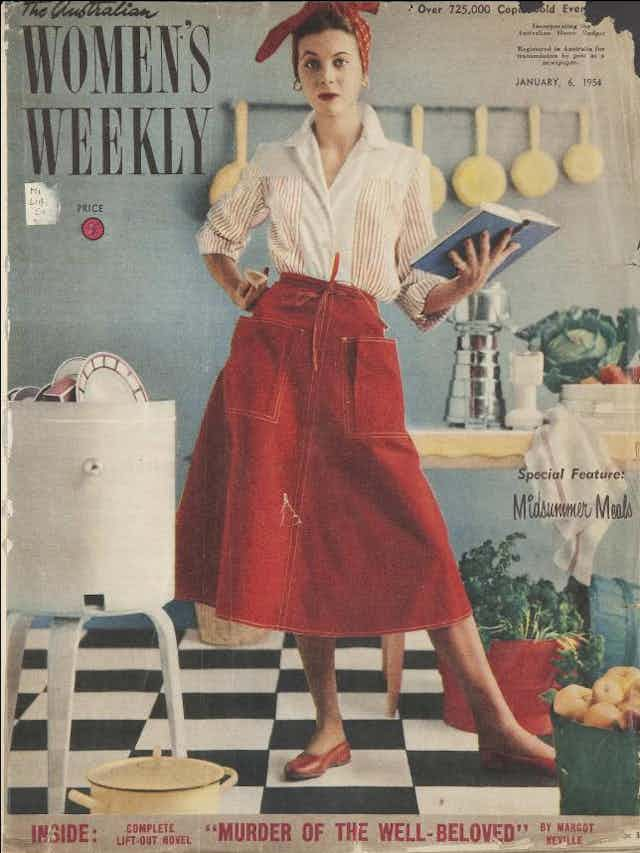

It focused on promoting a vision of the “everyday” Australian woman. Of course she did not represent all women — she was white, middle class, not working in paid employment and devoted to her home and family. Articles on fashion, cooking, homemaking, motherhood and romance supported this image.

But the Weekly also saw itself as a “women’s paper” with a responsibility to educate its readership by including current affairs and news stories in each issue.

While we might not think of the 1950s housewife as taking an active interest in Cold War politics, a close reading of the Weekly – the “popular face of femininity” – shows Australian women were not only interested in global politics, but encouraged to join in the discussion.

The 1950s political landscape

The second world war had changed Australian society, particularly for women. As men were sent overseas, women filled the jobs men left behind. US servicemen charmed local women — who explored the new sexual and romantic opportunities available to them.

Though encouraged by the government to return to their homemaking duties, after the war, many women continued to work in paid employment and were more vocally interested in romance and sex.

By the early 1950s, meanwhile, the Cold War dominated international politics as the world split into two political blocs, aligned with the communist Soviet Union or the capitalist United States. Australia allied with the US, and fear of communism spread, with suspicion of anyone not following social norms.

Many Australians, particularly the middle classes, feared women would abandon their traditional family-focused roles. The family home thus became a symbol of peace and security and a bulwark against communist overthrow.

Female readers as thinkers

The Weekly was clear in the belief women should be engaged with Cold War politics. In 1955, after the first Taiwan Strait Crisis, Fenston rued “not one woman is directly concerned with the deliberations that may or may not lead to war”.

She encouraged her readers to take on a bigger role in these discussions, paraphrasing Alfred Tennyson’s poem Locksley Hall to profess her hope that in the future “women’s commonsense shall hold a fretful realm in awe” as they took an active part in diplomacy and politics.

On the topic of nuclear weapons, an article by the Canadian physician Dr Marion Hilliard in 1958 urged women to:

rise up and say: It’s time to stop. Let there be no more use of weapons which will let loose radioactive power in this world. My child, all the children of the world should have a chance to start life as sound in body and mind as possible.

Over the decade, Cold War topics were regularly combined with more socially acceptable feminine issues. In 1953, an article by Sylvia Connick appeared on the surface to be a simple romantic story of an Australian girl and a her Czechoslovakian fiancé.

But within this, Connick referenced the oppression of Soviet rule in Czechoslovakia and the horrors of communist labour camps.

The magazine positioned women as a distinct category of political thinker who had “instinctive” knowledge of how to conduct herself in political discussions with her contemporaries.

As Fenston wrote in an editorial on the 1954 Big Four Conference between France, America, Britain and the Soviet Union, while “the finer points of high-level diplomacy may be lost to many women”, women knew “tongues before guns” was a more effective political tool.

Using domestic analogies of “a quiet talk over the back fence” to describe international relations, Fenston suggested that women instinctively understood how diplomacy was more effective than the nuclear war tactics of “hurling rocks on your neighbour’s roof.”

Feminised politics

Reading the magazine’s Cold War articles, it would be easy to conclude the Weekly believed women were uninterested in international politics unless a feature also included comments on the latest fashion.

This would be a disservice to the magazine and its readership.

Instead, this approach is an example of what I have termed “feminised politics”. Overt political discussions were combined with conventionally acceptable feminine themes to avoid provoking widespread anxieties about social changes.

This feminised politics echoed the maternal feminism of the early 20th century, used by suffragists to argue women would bring a maternal morality to the political sphere, updated to fit with the changed social context.

Women’s political interests in the 1950s are often forgotten, sandwiched as the period is between the very public first and second wave feminist movements. But while the 1950s housewife did indeed spend a lot of time on homemaking duties, that did not mean she sat out the important political discussions shaping her world.