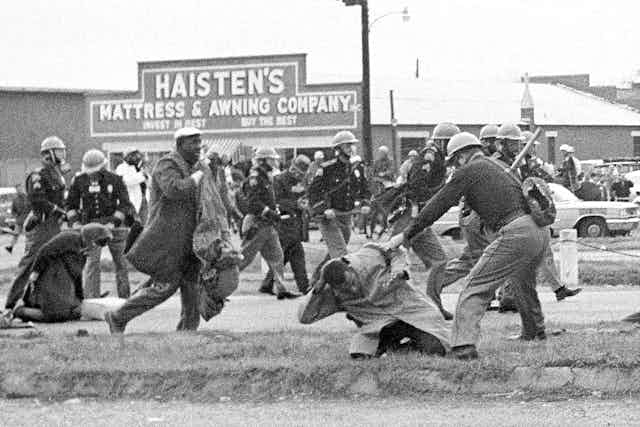

On March 7, 1965, Alabama state troopers beat and gassed John Lewis and hundreds of marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

TV reporters and photographers were there, cameras ready, and the violence captured during “Bloody Sunday” would go on to define the legacy of Lewis, who died on July 17.

I’m a media historian who has written about television and the civil rights movement. One of the remarkable features of the era’s media environment, dominated by the relatively new medium of television news, is how quickly certain events could roil the conscience of the nation.

Confrontations between police and protesters happened frequently during the 1960s. But a particular set of circumstances ensured that the images coming out of Selma galvanized politicians and citizens with remarkable speed and intensity.

A prime-time event

Most Americans didn’t see the footage on the 6:30 nightly news. Instead, they saw it later Sunday night, which, like today, drew the biggest audiences of the week. That evening, ABC was premiering the first TV airing of “Judgment at Nuremberg.” An estimated 48 million people tuned in to watch the Academy Award-winning film, which dealt with the moral culpability of those who had participated in the Holocaust.

News programs never got those kinds of ratings. But shortly after the movie started, ABC’s news division decided to interrupt the movie with a special report from Selma.

Viewers may have been peripherally aware of the marches that had been going on in the small city 50 miles from Alabama’s capital, Montgomery. Martin Luther King Jr. had kicked off a voting rights campaign there in January, and the media had been regularly reporting on the standoffs between Blacks who wanted to register to vote and Selma’s racist, volatile sheriff, Jim Clark.

Two years earlier, footage and photographs of Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Connor loosing police dogs and high-powered fire hoses on nonviolent marchers so alarmed the Kennedy administration that the president felt compelled to finally put forth a robust civil rights bill to dismantle Jim Crow segregation in the South.

But until Bloody Sunday, nothing had emerged out of Selma that gripped the nation’s attention. Even the Birmingham images didn’t have quite the immediate impact of those from Selma.

That’s largely because the special report interrupted a prime-time broadcast. But there was also the fact that the footage from Selma thematically complemented “Judgment at Nuremberg.”

In the days after the news film aired, a dozen legislators spoke on the floor of Congress linking Alabama Gov. George Wallace to Hitler and its state troopers to Nazi storm troopers. Ordinary citizens made the same connections.

“I have just witnessed on television the new sequel to Adolf Hitler’s brown shirts,” one anguished young Alabamian from Auburn wrote to The Birmingham News. “They were George Wallace’s blue shirts. The scene in Alabama looked like scenes on old newsreels of Germany in the 1930s.”

In the ensuing days, hundreds of Americans jumped into planes, buses and automobiles to get to Selma and stand with the brutalized marchers. The landmark Voting Rights Act passed with remarkable speed, just five months after Bloody Sunday.

The spotlight finally shines on Lewis

John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was at the head of the line of 600 protesters. Their plan was to march 50 miles, from Selma to Montgomery, to protest the recent police killing of activist Jimmie Lee Jackson and to press Gov. Wallace for Black voting rights. Next to him, representing King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was Hosea Williams. King was back in Atlanta that day.

Lewis, in particular, is quite visible in the news footage, with the camera zooming in on his tan coat and backpack as the troopers advance and then plow over him and the marchers behind him.

However, when CBS ran its story about the march Monday morning, Lewis wasn’t mentioned at all. In fact, CBS’ Charles Kuralt framed the story as a clash between “two determined men” who weren’t there: Wallace and King. “Their determination,” Kuralt continued, “turned the streets of Alabama into a battleground as Wallace’s state troopers broke up a march ordered by King.”

Other national news outlets also tended to focus on King, who was often the only Black voice given a platform to speak on civil rights matters. The marchers, including Lewis, were little more than stand-ins for the important political players.

In recent decades, that’s changed. John Lewis has come to occupy a privileged place in the media once reserved for King.

But even the recent focus on Lewis – while much deserved – has the tendency to neglect the foot soldiers and activists who made the Selma campaign a success. Lewis’ organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, valued and cultivated grassroots movements and the empowering of ordinary people rather than organizing campaigns around a charismatic leader, which was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference model.

The Black Lives Matter movement, which also eschews the “great leader” approach, is very much in the spirit of John Lewis and his civil rights group.

The current waves of protests against police brutality and systemic racism have garnered massive media coverage and widespread public support, similar to what happened in the wake of Bloody Sunday. As Lewis once said, “I appeal to all of you to get into this great revolution that is sweeping this nation. Get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes.”

He uttered those words in 1963 during the March on Washington. But they apply just as much to protesters today.