“In the 1850s, thousands of Americans proudly called themselves ‘the know-nothings’ and formed a movement against migrants for the ‘purification’ of America. They were bragging about their lack of a clue about politics and rational argument,” my academic friend sighed over a coffee in London last week.

Because they were the only Democrats in the neighbourhood, my friend’s family had moved from Alabama back to the Old World. These days, the politics of the United States has turned into a similar whirlpool of awe and ridicule – but now you don’t have to be geographically bound to the country, as the digital realm makes the flows of controversial rhetoric spill over traditional boundaries of time and space.

The campaign between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton featured an unprecedented amount of memes, viral texts that proliferate on mutation and sharing. In my research, I look at how memes have become the fast food media of contemporary politics as well as mindbombs of political activism. They are absurd, politically incorrect, incomplete and require the knowledge of context to “get” the joke. But most importantly, they mirror public opinion and popular emotions on the subject.

Hillary Clinton’s office tried to appropriate the language of internet cultures and shape their campaign posters like memes. But they failed to detach from the composition and expression style of a traditional poster. Not bold enough for memes, not classy enough for placards, these visuals got stuck somewhere in the grey zone between the online and offline.

Donald Trump’s campaign, on the other hand, demonstrated conscientious engagement with social media. He made his presidential announcement on innovative live streaming app Periscope. His Twitter accounts gathered millions of followers – indeed, just the comparison of the main Twitter feeds of the candidates, not to mention the satellite accounts, reveals the disposition of forces: 11m followers for @HillaryClinton as opposed to 14m for @realDonaldTrump. It was probably the bold rhetoric of Trump’s statements that made them so shareable.

Into the twittersphere

Trump supporters, following their commander, ignored all the rules of political correctness, fair play and sensible campaigning, indulging in meme warfare in the viral meadows of social networks.

Not only did they coin specific memes to attack the democratic candidate for the FBI phone scandal and pro-war sentiments, but even tried to create what I call meme campaigns: chains of similarly styled provocative messages organised by a hashtag that are designed to have a certain effect.

They don’t always work – but they do reveal the mood of public opinion. Several account holders took time to persistently deploy memes accusing Hillary of a drinking problem on Twitter. But #DrunkHillary failed to engage other users. Meek dozens of “shares” and “likes” revealed that both pro- and anti-Clinton voters doubted the idea that Mrs Clinton was an alcoholic.

Another case, the #DraftOurDaughters campaign, demonstrated how memes can “bomb” unguarded minds and influence the digital crowds. This initiative looked more like professional campaigning. Many voters were concerned that Hillary’s support of military interventions abroad would result in sending female soldiers to the battlefield. In order to amplify this concern, pro-Trump users coined a range of smart fake posters that imitated the simple graphic style of authentic Clinton posters. As a result, some social media dwellers believed that the meme-looking controversial images were indeed coming from the Democratic candidate.

Trump himself was by no means safe from the meme battlefield, with social media users creating memes that engaged in a rather lethargic lambasting of the candidate’s groping practices, unorthodox hair style and lack of reason in his assertions. But these memes proliferated in a rather disconnected fashion. Criticisms of Trump were certainly in the air, yet Clinton’s supporters did not create many uniform, clearly-focused campaigns out of them.

What does it all meme?

This meme flood is demonstrative of at least two alarming trends.

First, the growing problem of attention deficit has had a significant impact on the course and outcomes of the election. The phenomenon of “attention economy” has been studied since early 2000s. In today’s environment of multitasking and media oversaturation, the scarcest resource is not money or talent, but attention. People can only concentrate on a print-size version of the text; as soon as they need to scroll down to read the rest of argument, they are most likely to close the link and move to the next tab.

According to Garry Linnell, in 1968, the average politician’s soundbite in the news was 43 seconds, by 1988 it was nine seconds, and in 2016 we barely hear them finishing a sentence. This is the attention deficit environment into which internet memes fit perfectly. Comparable to fast food, they satisfy your information hunger with glitzy, tantalising, succulent bites that have little nutritional value, yet feed you on a very superficial level, right here, right now.

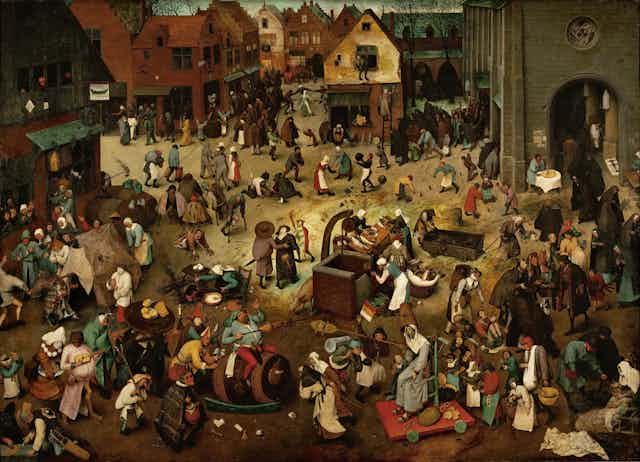

The second trend that the 2016 US election highlighted is the carnivalisation of public politics. Memes have been scrutinised as instances of medieval-like carnival: it is the logic of upside down, ridicule and mockery, stupidity and opposition to any possible elites.

Originally, of course, the carnival was limited to one week before Lent. People gathered in the central marketplace to unleash their desires and let off steam. The e-carnival is dramatically different: it expands beyond the constraints of time and space. It is ever present, and here to stay. Increasingly, attention-deficit voters draw their news and opinion from the fast food media communication and then return their inputs to the same shallow realm.

The consumption of fast food media advances fast politics, the swift, screaming and scandalous sort of politics that is so tempting to share and receive “likes” for. So the real winner of this election, in fact, is the viral state of mind. This renders the future of politics yet more worrying.

As Trump realised early on, the rule of this emerging memeworld is to share or be square, no matter the content.