In the opening of Netflix’s popular new show “My Unorthodox Life,” fashion mogul Julia Haart explains that she grew up thinking that dressing provocatively had eternal consequences:

“It was your mother’s responsibility to teach you modesty. … If any of your body parts were uncovered, there’s a very special form of hell that is reserved for both you and your mother. In this hell, your mother would dip your clothes in acid, put them on your body, and so throughout the day your body would decompose from the acid. And then the next morning it would start all over again, for thousands of years, or however many years hell lasts. When you learn this as a child, and everyone around you believes it, you believe it.”

Haart grew up in an Orthodox Jewish community she describes as “fundamentalist,” though critics have questioned how the show portrays it. In both Christianity and Judaism, views on the afterlife are diverse – and most Jews in the U.S. today put less emphasis on what happens after death than what happens now.

As a scholar of early Christianity whose work focuses on depictions of hell, I see this education as rooted in two millennia of ideas about gender, bodies, sin and punishment that influence our society today – particularly for women.

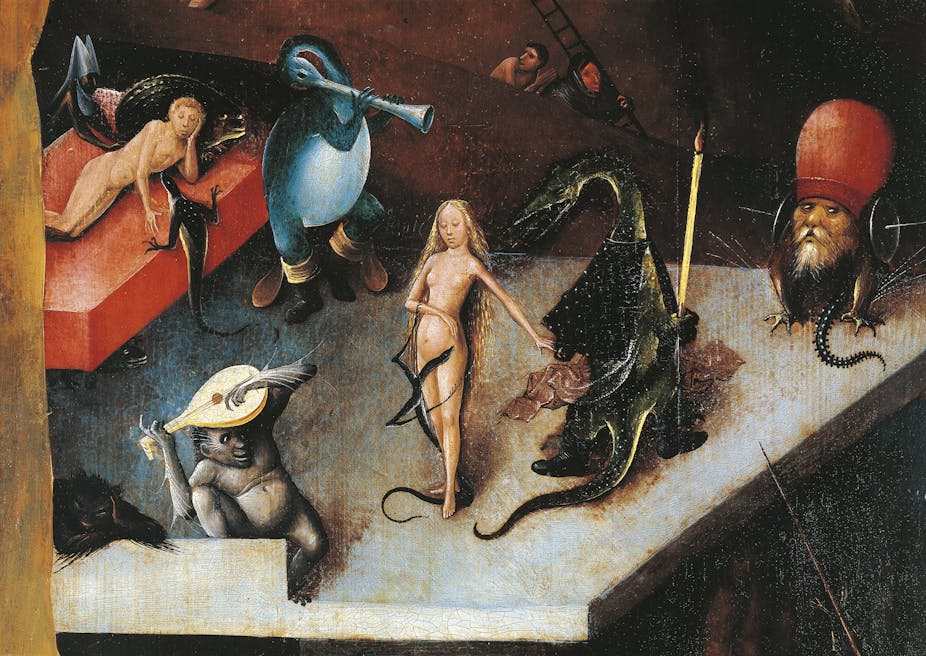

Some ancient Jewish and Christian depictions of the afterlife provide graphic depictions of sinners and their punishments. Many of these punishments are seen as “fitting” for the sin committed: They follow the ancient legal standard of “measure for measure” punishment, known as lex talionis.

Punishments for women, like the one that Haart describes, follow the norms of the ancient and medieval cultures that first created them, including drastically different expectations for men and women. In these texts, the “immoral” clothes that brought women to hell become the instruments of their own torment – threatening images used to keep them in their place.

‘Fitting’ the crime

Clothing is only the beginning. Women in hell hang by their breasts in several medieval Jewish texts known as the Isaiah fragments because they uncovered their hair, tore their veil or nursed their children in the marketplace “in order to attract the gaze of men.” In the Gedulat Moshe, a Jewish text written sometime around the 13th century that describes Moses visiting hell, he sees women who uncovered themselves hanged by their breasts and their hair.

These frightening visions were drawn from attitudes toward real women and were used to control them, as well. In a third-century rabbinic legal text, the Mishnah Sotah, a woman who has committed adultery is sentenced to have her breasts and hair uncovered. The public humiliation is considered “fitting,” because her body led to her sin.

But this idea of justice or retribution did not originate with the rabbis and is certainly not exclusive to Judaism. The punishments in these Jewish texts closely mirror the second-century Apocalypse of Peter, a Christian text that describes women hanging by their hair and neck because their intricate hairstyles seduced married men.

It is difficult to say whether it was Jews or Christians who first brought these gendered ideas about the body into their images of hell. But the earlier Christian visions of hell certainly elaborate on them more than medieval Jewish ones do. For example, only young women were punished for being unchaste in early Christian depictions of hell – even those like the Apocalypse of Paul, in which male and female sinners were punished equally for other sins.

In the earliest Christian descriptions of hell, women and men were both held accountable for parenting-related sins, such as abortion or abandoning an infant. After a few centuries, however, women alone were held responsible for having children and nurturing them. In one medieval account of hell, the Latin Vision of Ezra, women were not only responsible for parenting their own children but punished for failing to nurse orphaned infants. Their punishment? Hanging in fire while serpents suck their breasts.

These sins and punishments reflect several different but interwoven ancient ideas about the body: that women’s hair was a sexual organ, that female grooming is tied to adultery, that women’s main role is child rearing and that their bodies should not be seen in public.

Double standards today

Although these ideas were not included in the Jewish or Christian Bible, societies often used them to define religious crimes and control their bodies.

It is easy to look at these ancient hellscapes and dismiss them as long-ago. But ideas about women’s bodies being problematic and in need of control persist, with or without religion. And in “My Unorthodox Life,” Haart invites the audience to look at gender double standards in the fashion world up close.

Haart, who has left her Orthodox community, calls herself “very proud to be a Jew” and determined “to show people that there are all sorts of Jews.” Now CEO of Elite World Group, the parent company of a major modeling agency, she draws viewers’ attention to the industry’s sexual abuse, unequal standards for men and women, and its tendency to cater to male desire. She describes her mission as “cleaning up” modeling and “rooting out” its sexual abuse – a vow a former supermodel has recently called on her to uphold.

Though “My Unorthodox Life” has been mocked for its soap opera style, I believe it carries a serious message: Ideas about objectifying and controlling women’s bodies shape our society more than we’d like to admit – with or without religion.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]