In February 1992, a Venezuelan colonel called Hugo Chávez, together with other officers from a movement that had formed within the military, led an unsuccessful coup attempt against the country’s deeply unpopular government. Two years later, on the day he was released from prison having served time for his role in the failed coup, Chávez was asked by a journalist if he had a message for the people of Venezuela. “Yes,” he replied: “Let them listen to Alí Primera’s songs!”

Within five years, having formed a new political organisation and mounted a campaign rooted in these very songs, Hugo Chávez was elected president of Venezuela with 56% of the vote. On February 2 1999, he became the first head of state without links to the country’s establishment parties in over 40 years. Chávez won three more general elections in what former US president Jimmy Carter has described as the best electoral process in the world, remaining president until his death in March 2013.

It was the music legacy of Alí Primera, a hugely popular Venezuelan singer/songwriter, that enabled Chávez to link his political movement with grassroots activism. Yet in spite of the surge in international attention that Chavismo attracted throughout this time, the government’s profound links with Primera’s music legacy have been almost entirely overlooked outside the country. Chávez’s frequent quotation and singing of these songs in speeches and on television seems to have been regarded as merely an amusing or entertaining aside, quite separate from the main business of governing.

But my research shows that music is much more than a form of entertainment. In Latin America, where illiteracy remained relatively high well into the 20th century, and where the official media are widely perceived to represent the interests of wealthy elites, songs – so easily remembered and transmitted – play an important public role. Chávez used Primera’s songs as cultural resources to construct a political persona that identified him profoundly with the masses of late 20th-century Venezuela – and they with him.

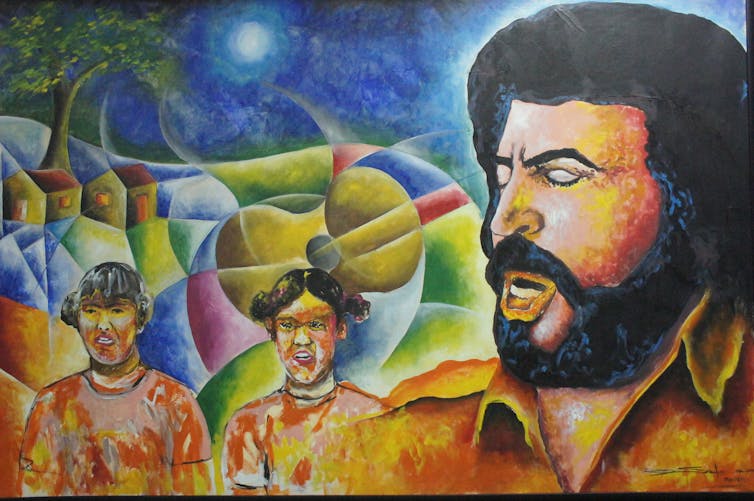

Alí Primera

Raised in rural poverty in the shadow of Venezuela’s largest oil refinery in the Paraguaná Peninsula, Primera was Venezuela’s best-known Nueva Canción singer/songwriter.

The Nueva Canción (New Song) cultural movement emerged in the 1960s. Inspired by the success of the Cuban Revolution, and seeking to counter the perceived cultural colonialism of the United States, Nueva Canción composers sought to transform their societies in favour of the marginalised masses. They revived local folk music forms which, having been widely suppressed during the colonial period, carried profound associations of resistance to elite rule. They wrote lyrics that highlighted the everyday lives and struggles of the rural and urban poor.

Protest formed part of their activities, but as a movement, Nueva Canción was primarily interested in promoting national concerns, regional integration, and independence from US economic, political and cultural influence. As the Uruguayan Nueva Canción singer/songwriter Daniel Viglietti put it, the movement was not de protesta (about protesting) but de propuesta (about proposing alternatives).

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, Primera wrote and performed songs that denounced the economic, cultural, political, racial and environmental impact of the oil industry on his country. With his independent label Cigarrón, he recorded 13 albums, which were widely banned from mainstream media outlets. He remained openly defiant in the face of increasing harassment from state authorities who, he reported, viewed him as a dangerous subversive who encouraged “non-conformity”.

His sudden death in a car accident in February 1985 was widely rumoured to have been ordered by state officials to silence a “troublesome” voice – although no firm evidence for this has ever emerged. Popularly seen as a martyr who died fighting for the poor and the marginalised, Primera and his songs rapidly passed into the realm of myth. His songs united Venezuelans in their denunciations of political corruption, increasing poverty levels and severe state oppression in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Hugo Chávez

By urging Venezuelans to listen to Primera’s songs, by singing and quoting from these songs and officially honouring Primera’s legacy via cultural policy, Chávez connected his government with the masses on whose behalf Primera was seen to have struggled. In February 2005, on the 20th anniversary of Alí’s death, the National Assembly unanimously agreed to declare Alí’s music legacy part of the nation’s official cultural heritage, and the newly organised Ministry of Culture financed an exhibition of posters, photographs, records and press articles, the production of two documentaries about the life and work of Alí Primera, and an album of heavy metal covers of his songs.

But this produced competing power struggles over who was best placed to legitimately interpret the songs “correctly”. Chávez supporters predominantly supported and understood the state’s co-option of Primera’s legacy to be an official recognition of their grassroots history of social and political activism. But many opponents contested the official representation of Primera as an “ideological root” of Chavismo. Others harnessed the oppositional qualities of the songs to express their resistance to the Chávez government via social media.

On March 5 2013, Venezuela’s then vice-president, Nicolás Maduro, announced on state television that President Hugo Chávez had died in Caracas at 4.25pm that afternoon “after battling a tough illness for two years”. Maduro then urged Venezuelans to be strong and not lose hope, and to use Primera’s songs to prepare for the future:

Let us take … the songs of Alí Primera … Let us rise with the songs of Alí and the spirit of Hugo Chávez, the greatest forces of this land, in order to face whatever difficulties we may have to face.

With the US president, Donald Trump, now facing pressure to heighten sanctions on Chavista officials, there is no doubt Venezuelans face many challenges ahead. But Primera’s songs remain one of the most powerful resources available to Venezuelans. Not only to imagine and share political alternatives, but also to defend, challenge and resist the legacy of Chávez.