Cultural capital is a rare and precious commodity. It is earned by doing – with wit, rigour and imagination. Being born to privilege may help in its accumulation, but that is not sufficient. These days, especially, privilege can be an impediment.

The advantages of David Marr’s birth proved more complicated than they first seemed, but attuned him to hypocrisy and made him a better observer. For five decades, he has honed his skills as an eloquent writer, dogged researcher and witty interlocutor with a strong moral core.

As a journalist and author of acclaimed biographies of Sir Garfield Barwick and Patrick White, he has become a trusted guide in the endless quest for public sense-making. His journey from a privileged son of upper middle class Sydney to wise national witness is captured in the 567 pages of My Country, the compelling collection of a “few” of his speeches and articles.

Over a lifetime, Marr has earned a fortune in cultural capital. He has now decided to spend some of it.

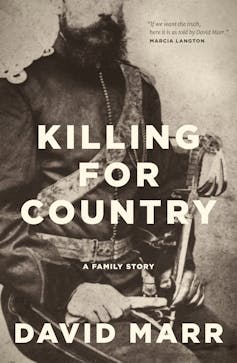

Review: Killing for Country – David Marr (Black Inc.)

The release of his harrowing and important book Killing for Country was timed to influence the nation-defining referendum on October 14. Four years ago Marr discovered another complication of his privilege: his forebears’ role in murdering scores of First Peoples during the land grabs that preceded the creation of Australia.

When Marr learned of this history, it was as though he had stepped into quicksand. Killing for Country is not the generic “why weren’t we told?” cry that has echoed around the continent for decades, and still resonates, but something personal. And as Marr discovered over years of painstaking research, the truth was much more brutal than he could have imagined. “I can’t argue away the shame that overcame me,” he writes.

Like most Australians of his generation, Marr grew up in a family and a nation that were good at secrets. Making your own life was a virtue, curiosity about those who came before was neither encouraged nor rewarded. In this, as he writes, “my blindness was so Australian”.

The killings that soaked the Great South Land with blood were documented in official memoranda tied with ribbon and shipped back to London, reported extensively in the press, and described in diaries and letters. They were the subject of periodic court cases and public inquiries.

Yet these records were persistently ignored. Many were destroyed. The public inquiries were rarely acted upon. Diligent historians like Noel Loos, Henry Reynolds and Raymond Evans were undertaking important work, scrolling through old newspapers in obscure country towns, but for most such a task was impossibly daunting. As a result, the trail died with time.

Crucially, many of the descendants of those First Peoples who survived and remembered often also chose to try to forget. The weight of the horror was too great.

This was perfect terrain for the myth of a dying race to take root and flower. And so it did. The newly minted Australians of the 20th century convinced themselves the killings that had once filled the pages of newspapers, and even became the subject of bestselling novels, were either necessary or not that bad, really. A poem that featured in many newspapers a decade before Federation included the lines:

We have no record of a bygone shame

No red-writ histories of woe to weep.

At the time, the killings in northern Australia were ferocious.

Secrecy and denial were baked into the founding of the nation, from the shame of convict origins to the violence of settlement. Australia was shaped with bloodshed and trauma.

Historical quicksand

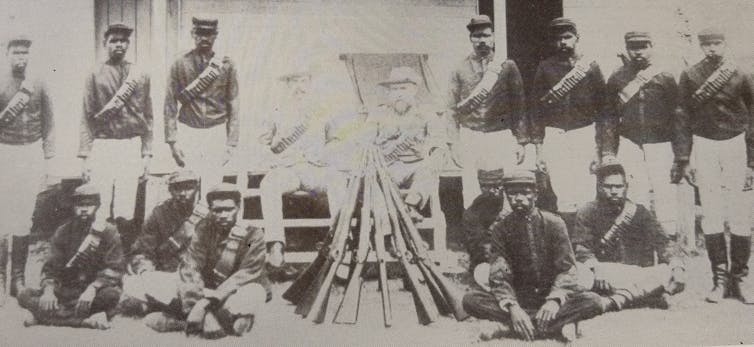

Marr found himself sinking into the historical quicksand of the violent reality after he tried to answer a question from an elderly uncle about his great grandmother Maud. There seemed to be a connection to the Queensland Native Police, and Jim Graham turned to his brilliant nephew to learn more. It seemed that Maud’s father Reg Uhr and his brother D’arcy had been vigilant members of the force. That fact was in Wikipedia, but there was much more to learn.

As Marr soon discovered, the scale and details were mind boggling.

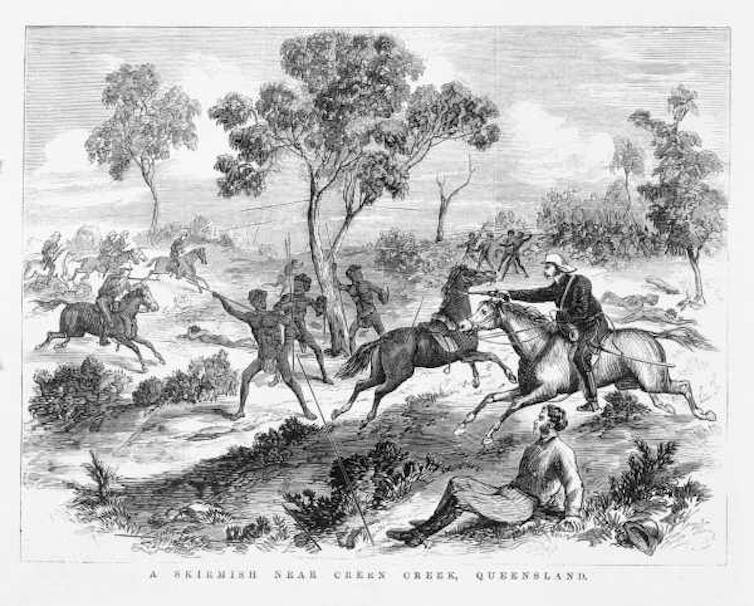

The Blackfella Films series The Australian Wars for SBS brought some of this to our screens last year and is now finding global audiences, scooping national and international awards. The violence of the Queensland frontier was even more vicious and protracted than in Tasmania. Native Police had first been used in New South Wales, but the unprecedented violence in Queensland was applied across northern Australia

In the last decade, scholars including Raymond Evans, Robert Orsted-Jensen, Jonathan Richards, Heather Burke, Lynley Wallis, Timothy Bottoms and others, have reassessed the number of lives lost.

The 442 officers and 927 troopers of the Queensland Native Police are now considered responsible for the deaths of 41,040 Indigenous people in that colony between 1859 and 1897, and approximately 3,500 in the decade before Queensland became a separate colony.

If the 20,640 Aboriginal people killed by private sorties, using guns and poison, and the estimated 1,500 colonisers killed by Aboriginal attacks are added, a horrifying tally of 66,681 is reached – in Queensland alone. At federation, its settler population was 498,129. It is now estimated that the Indigenous population of Queensland before the colonialists arrived was at least 350,000.

Developing a narrative of the role one’s forebears played in this murderous business is not a task to be taken on lightly. These stories mess with the heads of even the most experienced and detached researchers. If it is your own family, even if they were people you never knew, it has an even more troubling quality. An Indigenous colleague put it simply:

Your mob wrote down the colonial records, the diaries, and newspapers. You do the work. You tell that story. It’s your story.

Read more: The Australian War Memorial must deal properly with the frontier wars

Republic of newspapers

In many ways, the newspapers hold the key. They are a dominant source in Marr’s long, eloquent and detailed book. Using them is the perfect match of author and subject.

As a journalist, Marr is alert to the limits of his profession. His retelling of the battle to maintain the integrity of the Gazette – one of the several important early papers in Sydney – by Anne Howe, the widow who inherited it in 1829, glistens on the page.

In the 19th century, the colonies that later became a nation were distinguished by the vigour of their newspapers. The production of newspapers went hand in glove with the establishment of towns and regions. Most towns had at least one. Their owners were often prominent businessmen with local authority. The print culture was so vibrant that one British observer, R.E.N. Twopeny, described antipodean society in his influential report Town Life in Australia as a “land of newspapers”.

The newspapers of the day were often partisan, never shy of a fight. They could be eloquent and sarcastic. They were ready to settle scores, advance the interests of their owners, and blacklist journalists like Carl Feilberg and Arthur Vogan who challenged the prevailing established viewpoint.

But the newspapers also reported what was happening in unflinching language. Marr has drawn on this to recreate the business of claiming land, filling it with sheep and cattle, establishing towns and businesses, and “dispersing” (killing) those who had always been there.

Marr acknowledges the role his partner Sebastian Tesoriero played in finding and testing many of these sources. As archives closed during the COVID years, Tesoriero scoured Trove and became expert in tracing and interpreting the events reported in their pages. Trove keeps the focus tight. The digitised records of old newspapers, searchable in many ways, makes the task of following the story more straightforward than it was in the days of yellowing collections of bound newspapers or infuriatingly wobbly microfiche.

Killing for Country reverberates with details like this one, from the Brisbane Courier in 1874, about Native Police assaults at Skull Camp on the Palmer River goldfields:

A day or so after the murders [of three members of the Straher family] had been committed, Mr Inspector Coward, with Sub Inspectors Townshend and Douglas, came upon the black vagabonds and “quietly dispersed” them.

Killing for Country bristles with similar snippets from newspapers that not only provide insights into the thinking of the time, but underline the point that this was not happening in secret. In the land of newspapers, anyone who was paying attention knew what was going on in their name. The secrecy came later.

Marr supplements newspaper reports with diary entries and official reports, drawing on the support of a team of skilled archivists. But Killing for Country is very much a bottom-up, close-focus history, driven by story and character. It is primarily the story of Marr’s forebears. This provides him with a powerful field of vision, though it sometimes means the reader needs to deduce the wider context.

The machinations in official circles are rarely foregrounded, but they are there, shaping the way his protagonists behave. This is a deliberate and effective technique. There are many reports of the snide judgements of officials who were critical of the squatters, but who invariably eventually acquiesced to their demands.

Marr notes changing policies from London, their interpretation by local officials, and the efforts of the squatters to ensure their interests prevailed. As this is primarily a rich work of narrative, not analysis, readers are invited to draw their own conclusions.

Queensland was a violent place, less a product of London than the other colonies. In 1867, the Port Denison Times advocated that for every white life lost “we take, say fifty”. The Native Police in the new colony were given a mission, headed by Commissioner David Seymour, who also ran the constabulary police for nearly 30 years. They were led by privileged white men who had little training, and were often fuelled by alcohol. They used Aboriginal men from distant communities, enticing them into service with money, guns, food and horses.

Fine words from officials were of little consequence in such circumstances. Raymond Evans has highlighted this in an exchange between a Catholic missionary and the Minister for Lands in 1876:

Sometimes this [struggle] is styled war, although mere disparity of forces, especially of weapons and the helplessness of the black in such a contest suggests “massacre” as the appropriate term.

It is little wonder that many of the officers died young, drank to excess and that the periods of service of those on the ground in these ferociously hot and remote areas were often short. As Jonathan Richards has documented, mass desertions by Aboriginal troopers were common.

Read more: Friday essay: a slave state - how blackbirding in colonial Australia created a legacy of racism

On-the-ground colonialism

Marr’s account is no ordinary exercise in family history, not a simple who-do-you-think-you-are in search of a few skeletons and the odd black sheep. It develops into a monumental study of the on-the-ground nature of colonisation in New South Wales and Queensland, revealed through the stories of settlers who came in search of fortune for themselves and their extended families.

The complicated family genealogy Marr uncovers reveals a rich cast of individuals who grabbed the chances the new colony offered: buying and selling, whaling, importing shiploads of sheep to fill the vast acres they claimed, working their way into the centres of political and commercial power, making and losing fortunes.

A key character is Richard Jones, a self-interested man who arrived in New South Wales in 1809 as a clerk. He thrived, learning how to use his power for self-advancement, becoming a member of the Legislative Council and president of the Bank of NSW. Sometimes his pragmatic Christianity helped him draw the line, but he had no sympathy for Aboriginal people. As Marr writes,

Many dismissed him in his own day as pious and penny pinching. But Richard Jones was a great white carp in the colonial pond, half-hidden in the weeds, always feeding and always dangerous.

Marr’s forebears, the Uhrs, became part of Jones’ world through marriage. The links are clear, but the narrative includes a lot of people across several generations often with similar names. At times, I wished for a sketch of a family tree to help keep the characters in place and supplement the maps and fine drawings of individuals.

When Jones was declared bankrupt in Sydney in 1843, with debts of more than £48,000, he evaded most of his creditors. He set up shell companies and made his way north. Before he left, he secured his brother-in-law, “Edmund Blucher Uhr of Brisbane River Moreton Bay”, the position of Magistrate of the Territory and its Dependencies in 1845. It was typical of the way he used his personal capital to benefit his family. When times got tough, Jones and the Uhrs were always ready to use the special pleading their status bequeathed them to seek the security of a government job – as a magistrate, sergeant at arms, and as officers in the Native Police.

Before long, Jones had built another empire. His extended family claimed land and established businesses that depended on removing the people who had always been there. Their role in the violent creation of Maryborough is captured with an unflinching eye.

At the core of this narrative is a simple truism of colonialism: land is the ultimate commodity, the raw material of wealth. They were among the 450 squatters who had seized an area larger than Victoria before Queensland’s separation in 1859.

By the time the Native Police were disbanded, decades after Reg Uhr died and D’arcy had moved on to other battles in the Northern Territory and Western Australia, the land-owning squatters had lost much (but not all) of their power. By federation most of the properties claimed with such brutal force were owned by enterprises based in Sydney, Melbourne and London.

Read more: In The Australian Wars, Rachel Perkins dispenses with the myth Aboriginal people didn't fight back

Australian secrecy

Killing for Country begins with Marr’s quest to learn more about his great grandmother – an old lady with a crumpled face whom he last saw when he was eight, even though she lived for another decade. But she remains mysterious.

We learn that Maud’s grandmother appealed to the Colonial Secretary for her father Reg – who, after leaving the Native Police, had become a disreputable Cloncurry police magistrate and drunk for 20 years – to be transferred south. She wrote,

he has three children whom he is anxious to have Educated but he cannot afford to send them down here to school, so I do earnestly trust you will have him removed as soon as opportunity offers for my sake as well as his.

Reg died of a stroke a few days later, in August 1888, at just 44. The Western Champion described him as “a white man in every sense”.

What became of Maud and her siblings remains a mystery. How did she land in Sydney? What did she know of her father’s and uncle’s activities? Marr writes that no one told stories about her. She became invisible and silent.

This is the bedrock of Australian secrecy. Thousands of little stories that never made the newspapers or official reports. The First Peoples of this continent have, despite the catastrophic ruptures of forced relocation and child removal, nurtured their ancient and family storytelling; those who came later failed to even tell their stories to their children. This fostered a century of silence that made it possible for myths to flourish unchallenged, as the referendum “debate” has demonstrated in recent months.

Killing for Country does brilliantly for one group of families and a vast swathe of Queensland and New South Wales what a robust, locally grounded truth-telling process might do for the whole nation: it shines a light into the dark shameful corners of our collective national experience. What we will find when we look and listen won’t be pretty, but it is necessary to confront – not to be captives of history, but to learn from it and transcend it.

The Yolngu word is Makaratta: to come together after struggle.

An earlier version of this article mistakenly referred to Professor Heather Burke as Helen Burke.