When a person is rebuked by a judge twice in the space of half a year, the public could be excused for thinking ill of them. But when that person is the prime minister, it raises questions not only about his judgement but about the relationship between the government, the judiciary, and the rule of law.

In England and Wales, contempt of court is a criminal offence, punishable by up to two years behind bars – and yet Cameron has skirted the edge of this criminal behaviour more than once.

In recent months, he has twice been chastised by judges for potentially endangering the smooth functioning of justice. In both instances, he made remarks about individuals involved in live court cases, thereby potentially influencing jurors’ attitudes.

Twice burned

Back in December 2013, during the trial of two former assistants of celebrity cook Nigella Lawson who were accused of fraud, judge Robin Johnson told the jury that it was a “matter of regret” that Cameron had told The Spectator that he was a “massive fan” of Ms Lawson. Cameron, he said, had made remarks that could be construed as being “favourable to Ms Lawson”.

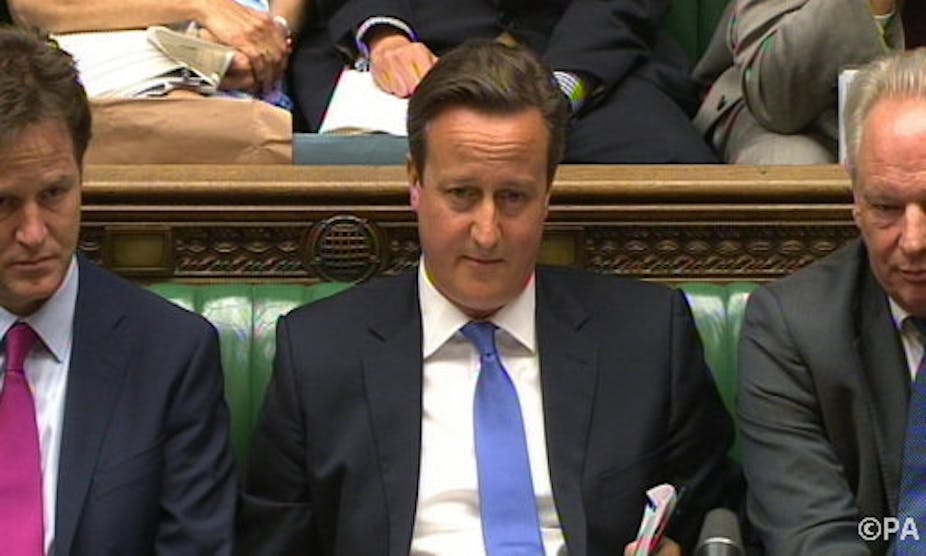

And after the phone hacking verdicts came out, Cameron commented on the conviction of his former communications chief Andy Coulson – despite the fact that whereas Rebekah and Charlie Brooks had been cleared of all charges against them, the jury was still considering two other charges against Coulson and Clive Goodman of misconduct in public office.

The trial judge, Mr Justice Saunders, was not impressed. He deemed Mr Cameron’s remarks “unsatisfactory so far as justice and the rule of law are concerned” and castigated him for providing a poor example to the media.

Saunders might not be the only one left fuming. With total costs close to £100 million, the trial is in Saunders’ estimation possibly the most expensive in British legal history. The Crown Prosecution Service and police’s bills alone have been put at more than £33 million – all funded by the taxpayer.

If the judge had gone a step further and decided that Cameron’s remarks had prevented the jury reaching an unbiased verdict, then we would have had the bizarre situation of the prime minister causing the collapse of the most expensive trial in his country’s history.

Courting disaster

Broadly, somebody or something is in contempt of court if it impedes the administration of justice. The Contempt of Court Act 1981 states that a published statement is in contempt if it creates a “substantial risk of serious prejudice” to the outcome of a case.

Normally, it is the media that has to worry about whether it’s in contempt. And in the post-Leveson climate, the government has been at pains to make sure the press is responsible, ethical and indeed law-abiding in its coverage – all of which makes Cameron’s remarks odder still.

And highly paradoxical, since he should have access to the best legal advice in the land when it comes to contempt issues. The attorney general, who decides whether to launch contempt proceedings, is himself effectively appointed by the prime minister and advises the government on legal matters. To confuse the issue further, a Downing Street spokesman said the prime minister had in fact taken “the best legal advice before issuing his (Coulson) apology”.

So, we have a situation where it seems the prime minister took the advice of the attorney general on a contempt issue, only for the trial judge to then suggest that the prime minister’s remarks were still close to being in contempt. The executive is thinking one thing, and the judiciary quite another.

Bad advice

The irony is that the attorney general’s office launched an initiative in December to educate the public about the dangers of making legally prejudicial statements. Dominic Grieve announced that advisory notes flagging up legal cases which could give rise to prejudicial statements would be published on Twitter, the aim being to reduce the chances that users of social media could commit contempt. Previously, the notices had only been sent to media outlets.

In another irony, Grieve made that announcement just eight days before Cameron was admonished by the judge in the Nigella Lawson case.

Given that the Attorney General is appointed by the monarch on the prime minister’s recommendation, is it ever realistic that a prime minister would have contempt proceedings brought against him, even for a flagrant breach? The prime minister and the attorney general in any given administration are colleagues and invariably allies.

What with both this constitutional arrangement and the events of the past six months, the current prime minister is in serious danger of appearing to put himself above the law.

Educating a smartphone-wielding public on the dangers of a careless tweet is one thing. But it’s vitally important that the attorney general and the prime minister make sure that the government’s (and specifically the PM’s) own remarks on legal proceedings are beyond reproach.

For if the prime minister can make legally questionable remarks and just about get away with it every time, why shouldn’t newspaper editors – or indeed you and I – chance our arm?

Next, read: Hacking trial was just round one in the fight to rescue journalism