The government’s recent proposal on EU citizens’ rights after Brexit included an offer to allow those resident in the UK to apply for “settled status”. This new status would be evidenced with a residence document, including the possible collection of biometric data.

The suggestion immediately raised concerns that the government was introducing ID cards by the backdoor. The previous Labour government’s plans to introduce national ID cards proved deeply unpopular and were ultimately scrapped by the coalition government.

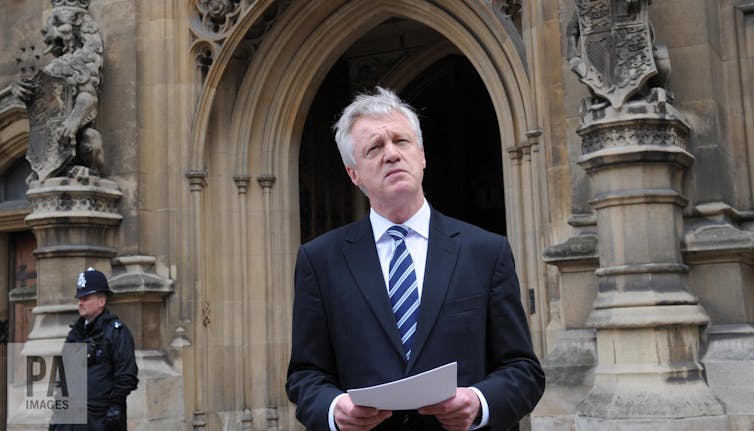

At first glance, the proposal seems deeply ironic. It was, after all, David Davis, the secretary of state for exiting the EU, who campaigned for so many years against ID cards. In 2008, when he was shadow home secretary, he resigned his seat in opposition to the then Labour government’s record on civil liberties. And in 2014, he launched a legal challenge against the coalition government’s Data Retention and Investigatory Powers Act, arguing that the government was infringing on civil liberties in seeking to store citizens’ data.

But in fact, his support for residence documents for EU citizens living in the UK shouldn’t be a surprise at all. Davis of course denies that EU citizens will be forced to carry ID cards – merely have “documentation” to prove their status. But despite his former abhorrence of ID cards, his backing of documentation for EU citizens actually fits neatly with his value system and conception of national identity.

When he resigned as an MP, Davis criticised what he called the “insidious, surreptitious and relentless erosion of fundamental British freedoms”. His opposition to ID cards was based on his argument that they erode the “hard-won rights of British people”. He did oppose ID cards for non-UK nationals too, but on the basis that their use would mark “the start of the introduction of compulsory ID cards for all by stealth” rather than a point of principle about the freedoms of foreigners in the UK.

His opposition to the EU has taken a similar form. Recently, he argued that remaining in the EU would sacrifice “real opportunities to improve the lot of our people”. In the same speech, he praised the historical foundations of the European project, but maintained that “this history is not our history”. Davis defends what he sees as “British” values, based on his understanding of British history and traditions.

Scholars have argued that there is a new cleavage in globalised societies between those who hold liberal, universalist values and those who subscribe to a more traditionalist worldview. The latter seek to defend exclusive communities based on shared cultural traditions. They tend to promote national sovereignty, restrictions on immigration, and traditional moral values. Such worldviews stand in opposition to universalist values that promote, for example, an internationalist outlook, cultural diversity, and human rights.

It’s clear that, for Davis, national identity is an exclusive concept. He has rejected the idea that he opposed ID cards because of libertarian values, calling himself a “rule of law enthusiast” who was defending, in his words, “the judicial tradition of Britain”. He also defends traditional moral values, by opposing same-sex marriage and calling for a reintroduction of the death penalty.

To Davis, being European is fundamentally incompatible with being British. He did not oppose ID cards because he is committed to the universal rights of the individual, but because he viewed them as contrary to “British traditions”. It is likely that in his view, EU nationals have little right to expect enjoyment of the “British freedoms” he has long defended. Rather, such rights are to be reserved exclusively for British citizens.

Closed club

The value divide that explains much of Davis’ politics also lies behind Brexit more generally. And pursuing this agenda will only deepen it. We know that identities become strengthened and more polarised in periods of crisis. In order to make sense of events such as Brexit, we interpret them according to existing identities and understanding of the world, which entrenches them further.

Since the referendum, the government has constructed a narrow and exclusive conception of the national community. Brexit has been framed as the clear and emphatic “will of the people”. This despite the narrow result and the fact that so many people who stood to lose rights were excluded from the franchise. The government’s proposal on EU citizens’ rights is merely a formalisation of this exclusive, traditionalist conception of the national community.

Studies have also shown that support for traditionalist values were a strong predictor of voting Leave. But when my colleagues and I conducted a survey of people attending the pro-EU March for Europe in London, we found that one of the most common concerns was that Britain is shifting away from being an inclusive, cosmopolitan, internationalist country, and towards intolerance and xenophobia. Many also expressed concern about a loss of human rights and environmental protections, and feared a breakdown of international cooperation and social solidarity.

On a personal level, EU citizens spoke of being treated as “second-class citizens”, unwelcome in the UK but, having been resident here for so long, also alien in their country of origin. And British citizens who voted for Remain expressed the feeling that they had been “robbed” of their European identities, that Brexit clashes with their fundamental, core belief in diversity and liberalism.

The proposal to create a de facto register of EU citizens means that they will be officially re-categorised as a distinct group with a smaller set of rights. They might be allowed to live in the same geographical space, but a division is to be drawn between British citizens and EU citizens nonetheless.

The government’s proposal to require EU citizens to prove their status with official documents does not clash with Davis’ opposition to ID cards. It actually allows him to defend the very same exclusive conception of “British traditions” that also drove him to oppose ID cards in the first place. His views reflect a broader division in the UK – and one that is not likely to disappear in the immediate future.