Ariane Beeston smashes the romantic myth of motherhood in her memoir Because I’m Not Myself, You See. In 20 short, gripping, sad and moving chapters, Beeston explains her frightening experience of postpartum psychosis and depressive illness as a new young mother.

Beeston is a Sydney-based writer and psychologist who formerly worked in child protection. Her memoir shares an enormous field of knowledge, lived experience and memories, including reflections and conversations with people who supported her through episodes of mental illness following the birth of her son, Henry, in 2011.

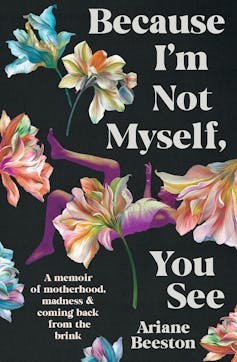

Review: Because I’m Not Myself, You See – Ariane Beeston (BlackInc)

Beeston first experienced symptoms of perinatal distress soon after his birth, which worsened over time. Baby Hen, as she calls him, appears to her as a dragon when he is a few months old, only three weeks after she returns to child protection casework.

I’m on my way home from work when my baby turns into a dragon. We are standing at the lights of a busy intersection, waiting to cross the road. […] It’s not the first time it’s happened. I’ve seen dragons before – in the cot, the swings, the highchair. But this one is angry and fierce and red.

Passages like this one are powerful and make this a brave book. It is also a generous book, allowing vulnerability and openness about postnatal mental illness to act as a flash point for other parents, mostly women, to see themselves in her story. Most of all, it reveals the profound loneliness of mothering.

Becoming a mother can shatter a woman’s sense of self. It can disrupt work and career trajectories and redefine relationships from the intimate to the most public of encounters. A woman’s bodily identity, sexual identity and professional identity can be reduced to almost nothing: to the nurse or doctor who is focused on her child, she becomes “mum”.

In Beeston’s account, her professional life working with the New South Wales department of community services, where she has taken babies away from their mothers, becomes a risk factor leading to her heightened sense of fragility following childbirth. She becomes hyper-aware of her own parenting.

From psychologist to ‘patient’

In her job as a departmental psychologist Beeston had to intervene in the most heart-rending of situations where children were potentially at risk, either because of parental “dysfunction” or issues like drug addiction.

These work experiences stay with Beeston as she has her own newborn. She becomes extra vigilant about his health and wellbeing, with her anxiety running high about nappy rash, breastfeeding and sleep patterns. The palpable shame and fear her narrative conveys is relatable and insightful.

Beeston’s account of her difficulty with breastfeeding will resonate with so many mothers who have struggled with this supposedly “natural” process, trying to get their baby to feed from sore and leaky nipples while stressed. Many new mothers have sought the help of lactation specialists and midwives and can feel they have failed if they “give up” too soon in favour of bottle feeding:

‘He just won’t latch on’, I text my mum. ‘Did you ever have this problem?’

Oh no, I never had any problems …Gosh, I remember breastfeeding one of you while cooking dinner …

Despite my experience of hotlines, I have never phoned one in my life. But I am desperate.

At first, Beeston writes, she tried to keep her hallucinations and delusions secret. But ultimately, she sought help and was admitted to the mother and baby unit of a psychiatric ward when Henry was 8-months-old. They stay there for three weeks. It was not the last time she needed to be hospitalised.

One of the things I like most about this book is the way Beeston is open about eventually seeking help, from hotlines, but also from her partner, Robb, and from her empathetic and smart psychiatrist Dr Q. These relationships feel like warm and practical hugs.

Beeston left her role in the department not long after her second hospital admission when her son was 15 months old.

Ultimately, over time, she learns to manage the illness with the help of regular psychiatric treatment and psychotherapy, medication for depression and anxiety, her family and ongoing support groups. She learns to love activities like ballet again. And she reads voraciously about experiences of motherhood.

You can feel Beeston’s heart swell when she writes about an older, now teenage, Henry talking to her about her experience and learning he had spent time in hospital with her as a baby, and visited her in treatment when he was two.

Part memoir, part self-help book

Feminists have written about the myths associated with motherhood, in particular, the unattainable goal of being a “good mother”: beyond criticism, always tidy, ready to please and to discipline her children in the right measures.

Motherhood is, as Beeston reminds us, a “rearrangement of the self”. We tell ourselves stories about becoming a mother to remind ourselves what happened, and to order and arrange it. At the time, the experience of new motherhood can be a blurry confused period, clouded by lack of sleep and hormonal highs and lows.

The term “matresence”, or the state of becoming a mother, was new to me. Beeston has read widely, from poetry and fiction to feminist literature and psychological theories of attachment and parenting styles. Her process of finding meaning from many books and disciplines reminds me of the competing expertise on offer for new mothers, which is often bewildering in its diversity.

Beeston aims to reproduce the confusion of her disordered states during the period of her illness, but also her self-awareness of these as someone who was trained as a psychologist.

Her book is part memoir, part self-help book. The chapters are capsule-like vignettes. These short pieces can be digested in smaller amounts, which is helpful because the book, despite being utterly compelling, is at times confronting to read.

In her descriptions of removing children from parents in crisis I found echoes of the fictional story of children living in out of home care in Bodies of Light, a carefully-researched novel by Australian author Jennifer Down. Beeston’s book also includes factual information, evidence-based research, a list of helplines and support, and further reading.

We learn there are distinctions made in the health professions between “perinatal mental health”, “postpartum psychosis” and “postnatal depression”. Many of us will have used the term postnatal depression without realising the spectrum of conditions that can manifest for new mothers. Perinatal depression and anxiety affects one in five women in Australia, and one in ten fathers also experience depression.

One of the most frightening aspects of Beeston’s account is the fact that severe forms of mental distress can be hard to detect, and are also sometimes ignored, which can have tragic results.

Suicidal ideation is one theme of this book. Recent news coverage of the suicide of a new mother in Queensland highlights this risk for women who do not get appropriate help or treatment at the right time. In other extreme cases women might also harm their own babies.

Beeston’s aim here is to educate and reduce stigma by sharing these experiences.

Leading up to the publication of her book she has spoken with health professionals including midwives. Beeston “hopes readers take some comfort in seeing aspects of their own experiences reflected on the page”. These might be the smallest of examples – such as feelings of being overwhelmed by being alone with a new baby – or more serious delusions and hallucinations.

Describing these issues allows Beeston to bring the seriousness of postnatal mental disturbance to the surface. Given the shame associated with not living up to the ideals of new motherhood, many women’s experiences go unacknowledged and remain hidden.

Relating to lived experience

Reading this memoir took me back to the days when I walked alone with a new baby in a pram around my neighbourhood.

Beeston reflects on her tendency to objectify herself in her early experience of parenting by reading her own medical notes.

I recall doing the same thing and, like Beeston, I found myself described as “independent” when in hospital, which most likely meant I was able to go the bathroom by myself a couple of days after a C-section surgery.

As I read this book I had the urge to dig out my records of motherhood. I have kept an exercise book for around 17 years now that details handwritten records of what my baby ate when she started to eat solid foods at around six months.

It is clear I took pleasure in her sustenance: baby rice, pear, apple, pumpkin, and of course, breast milk. I recorded her reactions: “gobbled up!”, “made face at apple”, “doesn’t love the taste”. Feeding my child was both pleasure and experiment.

Like so many other women, I once had a fantasy that motherhood would be beautiful. The everyday reality can often be messy, difficult, and hard to reconcile. This book reminds us such experiences co-exist with caring, striving and love, that families can emerge from the darkest of moments.

If this article has raised issues for you the national helpline for perinatal mental health and wellbeing can be found here.