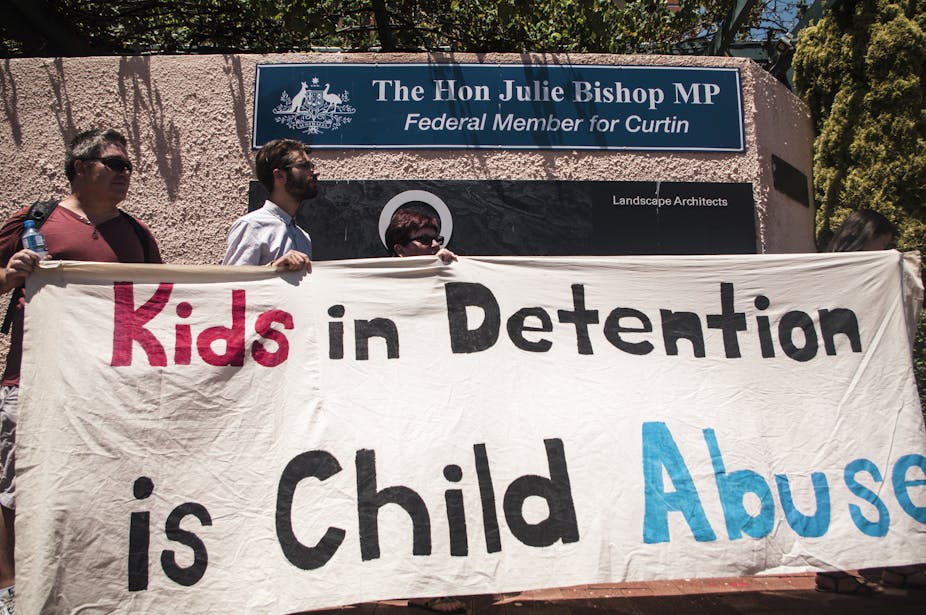

If you’ve been following the government’s attack on Human Rights Commission President Gillian Triggs and the commission’s report, The Forgotten Children: National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention, then you’ll know that her cardinal political sin has been to be partisan and politicised.

As Prime Minister Tony Abbott asked:

Where was the Human Rights Commission during the life of the former government when hundreds of people were drowning at sea? Where was the Human Rights Commission when there were almost 2000 children in detention?

Being partisan doesn’t mean party-political

Those who have come to Triggs’ defence have correctly pointed out that the Forgotten Children report takes Labor to task as well as the current government. And Triggs herself has denied that her report is politicised or partisan.

It’s true that Triggs’ report apportions responsibility for Australia’s brutal detention policies to both sides of politics. But in trying to deflect the government’s criticisms, we shouldn’t throw out partisanship and politicisation entirely.

In fact, a Human Rights Commission that isn’t partisan or politicised isn’t worth having.

How can a serious discussion of children in detention – or innocent people in detention whatever their stage of life – be anything other than political or partisan? Is the commission expected to say some nice things about mateship and Australia being a sport-loving country in its future reports to balance out the less savoury aspects of our national story?

A false ‘balance’ is not being objective

Part of the problem with criticisms of partisanship is the widespread misconception that it is the opposite of being objective and truthful. People who are partisan, according to this view, have an incomplete view of how things really are. If a more balanced view was taken about children in detention, for example, it’s assumed that things would look a whole lot better for the government.

But that in itself is to misunderstand partisanship. The truth is that partisanship and objectivity aren’t polar opposites. Properly understood, partisanship and objectivity are bedfellows. A measure of partisanship — and therefore politicisation – is required to be objective.

As Irish philosopher Terry Eagleton notes in his book After Theory:

Objectivity and partisanship are allies, not rivals. What is not conducive to objectivity on this score is the judicious even-handedness of the liberal. It is the liberal who falls for the myth that you can only see things aright if you don’t take sides … The liberal has difficulty with situations in which one side has a good deal more of the truth than the other — which is to say, all the key political situations.

Policy of deterrence is ethically confused

Abbott’s insistence that Triggs’ assessment of children in detention would be more acceptable if she were also to note the reduction in boat arrivals perpetuates this myth of even-handedness. On Abbott’s reasoning, once you take into account the reduction in the number of drownings, the practice of locking up kids supposedly becomes a defensible enterprise.

Of course, it isn’t. The two don’t – and cannot – balance each other out in a way that is ethically acceptable.

On the contrary, once you try to square things up in this way, Australia’s policies on detention, as enacted by both of the major parties, are even more barbaric. What Abbott and his supporters are effectively saying is that locking up some human beings is defensible if it dissuades other ones from stepping on to leaky boats.

Such a calculation flies in the face of a whole tradition of ethical thought, stretching back to at least Immanuel Kant, who holds that people are only ever to be treated as ends in themselves – rather than as a means to an end.

Against such a backdrop, it might have been best for the Abbott government to simply take the criticisms of the Human Rights Commission’s report on the chin.

Discussion about the timing of the Forgotten Children report and charges of partisanship are nothing but a beat-up by a government desperate for a distraction from ongoing leadership woes.

While human rights commissioners, journalists and academics – and anyone else who is in the business of seeking truth – have an obligation to avoid partisanship to a particular party or party line, Triggs’ report has avoided that, as any non-jaundiced reading of her report shows.

But we should never accept that a Human Rights Commission ought to be non-partisan or depoliticised. Without both, it would be incapable of doing its job.