More and more Ukrainians are switching from speaking Russian to speaking Ukrainian. In the media, this language shift is frequently portrayed as recent, dating back to the Russian invasion of February 2022. But the invasion was not the trigger. It was merely an accelerator.

To understand Ukraine as a nation, it is important to understand what is behind the shift and the dynamics of the nation’s linguistic ecosystem. It is equally important to recognise that, in modern Ukraine, language practices do not necessarily predetermine cultural and political views.

The “language question” in Ukraine goes back centuries. It is deeply rooted in the history of old empires and Ukraine’s position as the “borderland” between the West and the East.

Ukraine has been subjected to centuries of enforced Russification. This has involved the systematic persecution of the Ukrainian culture and language. The place of the Russian language in the Ukrainian society is the result of official and covert language policies by the Russian empire and the Soviet Union, both of which promoted the use of Russian and discriminated against the Ukrainian language and its speakers. Generations of Ukrainians grew up speaking Russian.

During the “Ukrainisation” of the 1920s, Ukraine experienced a period of reprieve. The language flourished. There was an increase in Ukrainian publishing and in the number of Ukrainian schools. Ukrainian was the language of the theatre and state affairs.

But this was short-lived. A much longer period of persecution followed, undertaken with the aim of destroying Ukraine’s national and cultural identity. During the Soviet era, educated elites were arrested in large numbers, sent to the Gulag, killed.

The story of the Ukrainian poet Vasyl Stus is one of many. Accused of “anti-Soviet activity”, he spent much of his life in prisons and labour camps. He died in prison in 1985, the year Mikhail Gorbachev came to power and six years before Ukraine’s independence.

Russia’s war in Ukraine is a colonial war. Vladimir Putin’s narrative recalls the historical legacies of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. It also entails the practices of linguistic imperialism – the imposition of one dominant language on the speakers of other languages.

Putin is once again playing the two languages against each other. The pretext for his incursion into eastern Ukraine in 2014 was the need to “protect the Russians and the Russian speaking citizens in Ukraine”. This rhetoric escalated in February 2022 to claims of “humiliation and genocide perpetrated by the Kyiv regime” on the Russian speaking population in the east. The aggressor is playing the victim.

In claiming that all Russian speakers belong to Russia and Russian culture, Putin is using language as both a pretext and a tool of expansion. At the same time, he denies the existence of Ukraine as a state. He wants to downgrade Ukrainian to a Russian dialect because, according to his playbook, if there is no national language, there is no nation.

Read more: Ukraine as a 'borderland': a brief history of Ukraine's place between Europe and Russia

Language context

On March 9 2023, Russia launched one of its biggest attacks of the year: 84 missiles targeted Ukrainian infrastructure across the whole country. The sirens went off in all regions.

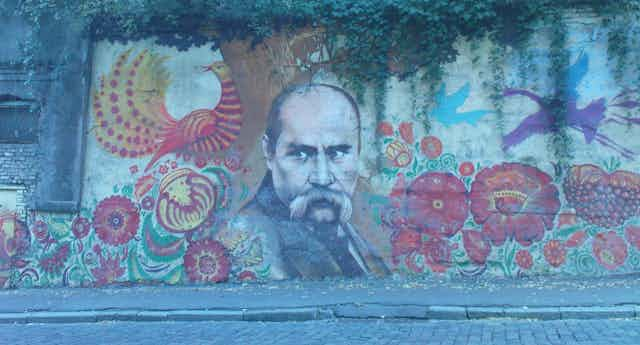

This date was not random. March 9 is the birthday of the 19th century romantic poet Taras Shevchenko: an artist, a bard, a writer, a free spirit, and a relentless fighter against the Russian empire. Shevchenko is a symbol of Ukraine and a symbol of resistance.

“Ukraine, Ukraine! My heart, my mother!” wrote Shevchenko. “When I remember your fate, my heart will weep!”

For the Kremlin, the goal is to eradicate Ukrainian identity by any means possible. Alongside indiscriminate shelling, killings, torture and rape, Russian forces have attacked schools, universities, museums, monuments and cultural centres. In occupied territories, they have changed town and street signs into the Russian language, thrown Ukrainian books onto the streets like piles of garbage, and changed the Ukrainian-based school curriculum to one that is Russian-based.

The linguistic landscape of Ukraine includes a large number of languages: Crimean Tatar, Romanian, Greek, Hungarian and Polish, among many others. But Ukrainian and Russian are the two major political players. Ukrainian is the official language and is used in all domains of public life, but Russian, together with the languages of other minorities, is afforded constitutional protection that allows for its free development and use.

On the surface this looks straightforward, but it is not. Language affiliation has long been a subject of political controversy. Changes to language policies often received mixed responses from those who use Russian as their dominant language and those who use Ukrainian.

Since the independence of the Ukrainian state in 1991, language has become a contested issue. In 2012, there was a brawl in the Ukrainian parliament over a regional language bill that would make Russian another official language in parts of the country. The bill was viewed as a threat to the future of the Ukrainian language.

After the EuroMaidan revolution of 2013-14, which ousted the pro-Russian government of Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine pursued closer ties with Europe. But for a time it avoided the active promotion of Ukrainian, not wishing to provoke alienation and discontent among Russian-speaking Ukrainians.

Who is the Russian speaker in Ukraine?

This is an important question in the context of the present war.

A Google search on the use of the two languages brings up maps from the 2000s, depicting the percentages of Ukrainian and Russian first-language speakers by region. These convenient but oversimplified accounts, frequently based on the 2001 census, do not reflect the rapidly changing language ecosystem. They are problematic in many ways.

Any linguist working with speakers from a multilingual speech community will tell you how difficult it is to disentangle such concepts as “first language”, “dominant language” and “mother tongue” (“рідна мова” in Ukrainian). In the minds of the speakers, boundaries are often blurred. Definitions imposed by researchers may mean different things to different people. In multilingual societies, a “dominant language” can be different from one’s mother tongue.

Binary depictions of Ukrainian and Russian speakers as distinct groups tend to overlook bilingualism as a characteristic feature (even if that bilingualism is passive).

Questions about one’s language are also likely to elicit responses driven by language attitudes and language politics at particular moments in time, as well as practices and attitudes within families and communities. Speakers themselves do not always know or think about why they use one particular language and not another at any given point.

Bilingualism and diglossia

Over two decades have passed since the last census. Ukrainian society has undergone dramatic changes. These have led to further strengthening of the civic identity, binding the population across all regions of the country, regardless of their ethnic and linguistic backgrounds.

During the Soviet era, the two languages were allocated different social functions, a phenomenon commonly referred to as diglossia.

Russian was a “high” language. It was prestigious. It was associated with power and social status. It was the language of education, the media, the government; it opened doors to education and employment opportunities.

Ukrainian was viewed as a “low” language – a provincial language with little prestige. It was associated with weakness.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian lost its status which had “entitled it to virtually unlimited use” and Ukrainian became the official language. But for some time the Russian language held its symbolic power in the collective psyche. Ukraine was experiencing a colonial hangover.

I still have memories of how one could be ridiculed for using Ukrainian in everyday communication in the early 1990s. I grew up in the large industrial city of Dnipro, where Russian was spoken everywhere. At my school, it was the language of communication outside the classroom, shared by teachers and students. The only person in the school who spoke Ukrainian at all times was the teacher of Ukrainian language and literature. The students were often cruel and laughed behind her back.

Most Ukrainians are bilingual or multilingual. Almost everyone has had some exposure to, if not schooling in (depending on age group and region), both Ukrainian and Russian. Post-independence language practices include code-switching, alternation between the two languages in the same conversation, and non-accommodation – an interaction where speakers use their preferred languages.

To further blur the lines between Ukrainian and Russian, there is surzhyk (“суржик” in Ukrainian), a mixed Ukrainian-Russian language. This is a pejorative label often used to refer to non-standard, broken language, but for some Ukrainians it is a mother tongue.

These complex conditions have created an environment with different degrees of bilingualism and varying levels of linguistic proficiency in both languages. The population in the Eastern parts of Ukraine, often portrayed as Russian speaking, is largely bilingual, with Ukrainian as the second fluent but passive language.

Language and identity

Following the Orange Revolution of 2004, and the EuroMaidan revolution of 2013-14, many first-language Russian speakers saw no reason to switch to the national language. They viewed Ukraine as a nation based on free choice rather than any ethnocultural characteristics.

Laada Bilaniuk, who has spent years researching language politics and practices in Ukraine, has written about the gradual trend of “linguistic conversion”: the decision to change one’s daily linguistic practices from Russian to Ukrainian.

This process began around the time of the fall of the Soviet Union and continued after Ukraine declared independence in 1991. It gained many more followers after Russia’s incursion into Ukraine in 2014.

Bilaniuk’s research found that many people from both Russian and Ukrainian ethnic backgrounds made a conscious choice to switch to Ukrainian. She suggests “[l]inguistic conversion to Ukrainian is an assertion of agency through active construction of one’s personal identity, which has the potential to shift the overall linguistic landscape and narratives of belonging in the country”.

Since Russia’s attack on the east of the country in 2014, the Ukrainian language has become the main cultural symbol of Ukrainian identity, even as it co-exists with the other languages of Ukraine. Ukrainians whose mother tongue is Russian are still Ukrainian. Ukrainians whose mother tongue is Crimean Tartar are still Ukrainian.

Because Ukraine is multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic, the construct of Ukrainian national identity has always had a civic component. Contrary to Putin’s false claims, the Russian language is not tied to any regional identity. For a large number of Ukrainians in the eastern and southern regions, Russian is viewed simply as a means of communication.

Following the full scale invasion of 2022, more and more Ukrainians whose mother tongue is Russian have rejected the language of the “enemy”, the “invader”. In doing so, they are asserting their national identity and showing unity and solidarity. The choice of speaking Ukrainian is political.

Sasha Dovzhyk’s powerful and intimate story about her conversion to Ukrainian will resonate with many Ukrainians.

What does the future hold for the Russian language and for the languages of Ukraine? It is for Ukrainians to decide and for researchers to document. Every personal history, every language history, every tragedy of this barbaric war is interconnected.

In the words of Olesya Khromeychuk – a historian, a writer and a relentless advocate for Ukraine – it is up to us, Ukrainians, to ensure that Ukraine “appears on our mental maps. And it stays there. With the borders intact.”

Language shifts in times of war are common, but it seems premature to jump to conclusions that Russian will vanish from Ukraine in a decade. Russian is still a mother tongue for a lot of Ukrainians. What is more important is that, even for those who do not use Ukrainian regularly, the Ukrainian language holds symbolic power. It speaks of an attachment to Ukraine itself.