AFTER THE INTERVENTION: Peter Billings from the University of Queensland interrogates the legal basis for the Intervention and suggests some new approaches.

The belated release of a 2010 review of Government indigenous programs has once again raised the issue of whether programs are helping the people they’re supposed to help.

The review found considerable scope to rationalise programs and called for better evidence on whether programs were working. Overall, it said, “past approaches to remedying Indigenous disadvantage have clearly failed, and new approaches are needed for the future”.

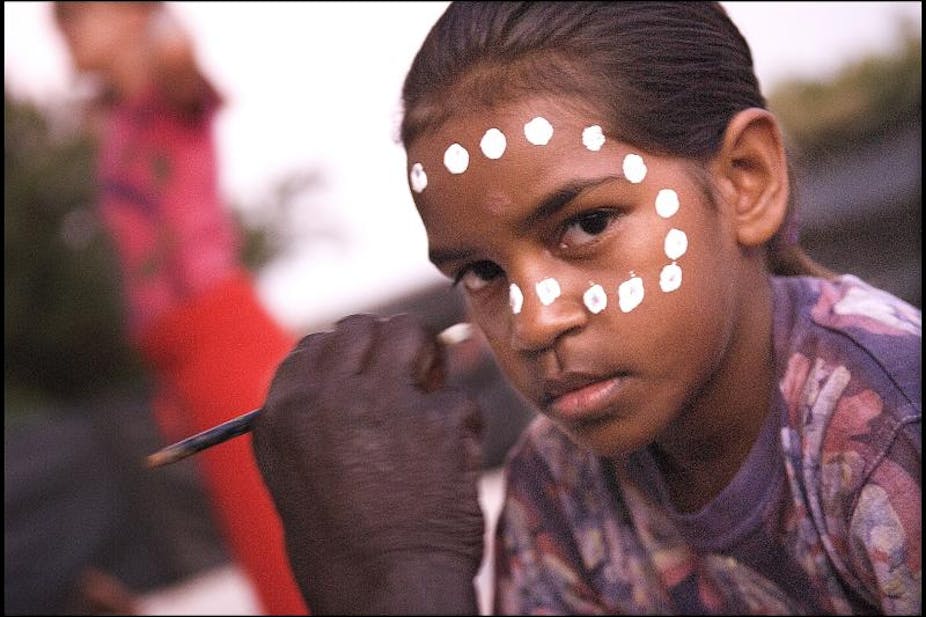

Of course, one of the biggest and most contentious programs in recent years has been the Commonwealth Government’s wide-ranging Northern Territory Emergency Response (or “Intervention”). The Intervention began in June 2007, based upon the urgent need to address child neglect and social dysfunction in certain NT communities.

Criticisms have been directed toward:

its blanket application and punitive effect; the erosion of the rule of law

its incompatibility with international laws, including prohibitions on racial discrimination

the return to an era when Indigenous peoples lacked agency, autonomy and citizenship rights.

Conversely, Marcia Langton observed that whatever its shortcomings, the Intervention was a great opportunity to overcome the systemic levels of disadvantage among Aboriginal Australians. The Intervention laws enjoyed bipartisan political support.

The Intervention addressed the protection of children’s rights, recognised in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. It privileged such rights over others, including the prohibition on discrimination and equality before the law.

While no-one disputes the obligation to protect children - they are the most vulnerable elements within any social arrangement - the question for many critics was whether other acknowledged rights must be sacrificed in their service.

Have 2010’s reforms made a difference?

This critical issue was, seemingly, addressed by the Labor government in 2010 via legislation (Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment (Welfare Reform and Reinstatement of Racial Discrimination Act) Act 2010 (Cth)). This modified the original Intervention.

The Act was geared towards protecting the human rights of the vulnerable. It was presented as a response to the calls for a proportionate and non-discriminatory response to socio-economic disadvantage in the Territory.

Significantly, the RDA 1975 (Cth) was reinstated. Income management had previously been indiscriminate: all social security recipients in particular localities were subject to welfare quarantining, regardless of their personal circumstances. The 2010 Act introduced a more targeted regime.

Labor claimed that the introduction of targeted income management, and its extension to other disadvantaged parts of Australia was justifiable. They said the operation of income management was an effective tool to reduce levels of deprivation, promote individual responsibility, and give people financial security.

While the new scheme of income management is intended to be mainstreamed across Australia, to date its roll-out has been confined to the NT. A strong case can be made that its disparate impact on Indigenous welfare recipients involves indirect discrimination contrary to domestic and international law.

The NT contains 24 of the 50 most disadvantaged locations in Australia, measured by the Socio-Economic indexes for Areas. By failing to extend income management to the other 26 areas during 2010-11, the new scheme has made little practical difference to the racially discriminatory effect of income management.

It should be noted that Labor intends to extend income management to five new disadvantaged locations, in several States, from July 2012.

Has income management protected children?

So was the original form of income management in the NT successful in meeting its primary aim of protecting children? Did it fulfil its secondary purpose of promoting people’s general wellbeing?

This has been hotly contested. Community opinion is polarised about the purported benefits it has realised. The evidence-base is equivocal.

In addressing such concerns, the Senate Community Affairs Legislation Committee noted that it is hard to find a comprehensive evidence base for almost all areas of social policy development. Such “complexity of social policy rarely allows for controlled experiments or definitive findings”, they add.

Many views on consultation

A further difficulty with Labor’s legislative re-design of the Intervention was the way it consulted with affected communities. The Government claimed consultation was conducted in the spirit of genuine engagement with Indigenous people.

But did the consultation process elicit a fair representation of people’s views? This has been disputed by the authors of the well-publicised report, Will They Be Heard?

Specific criticisms levelled at the process were:

it was biased towards the Government’s agenda

proposals tabled for discussion were restrictive

a lack of interpreters contributed to poor understanding by community members.

These allegations have been refuted by officials. Failing to consult Indigenous peoples, in good faith, is contrary to Australia’s obligations under international law.

Outcomes from the Intervention

Recently published research by scholars at the Menzies School of Health Research, points to rapidly rising levels of reported child neglect and abuse, but not a corresponding rate of increase in substantiated cases of child maltreatment.

The researchers argue that the unilateral measures of the 2007 Intervention ignored the complexities of the behaviours involved in child abuse and neglect and the variations between individuals, families and communities that it targeted.

In their considered opinion, community education and development work, together with therapeutic efforts regarding the abuse and neglect of children, are critical.

The authors also contend that income management may have altered expenditure patterns, but say quarantining welfare payments will not necessarily result in a decrease in spending on alcohol. Nor can it be safely assumed that the incidence of domestic violence and children being at risk will diminish.

The authors suggest that income management will be most effective where it is employed in tandem with other “wrap-around” support services. Worryingly, much of the available evidence to date suggests that the perceived benefits of income management (in the NT, Cape York and WA) have been seriously compromised by deficiencies in both administrative implementation and support service delivery.

Some approaches that may work

Indigenous people have the right to be consulted and to initiate and participate in the design and delivery of programs to address their safety and well-being. This consultation is crucial to the long-term prospects of success in tackling Indigenous disadvantage and closing the gap.

Moreover, independent monitoring and evaluation of such strategies is vital. The integrity of the evidence-base previously relied upon by the Commonwealth to justify the application of certain measures, such as income management, is questionable.

There is evidence that some progress is being made in relation to child protection. The statistics point to increased reporting and, therefore, greater awareness of child neglect across the NT. However, the Commonwealth’s most recent report card on the NT Intervention indicates that, overall, the purported benefits of the measures can’t be determined.

The critical challenge now is to ensure that there are appropriate responses to the increased levels of reporting of child maltreatment. In particular, the recommendations of the 2010 NT Board of Inquiry into child protection must not go unheeded: responses to child abuse must be proactive, focus on prevention and collaboration, entail greater Aboriginal involvement in service delivery and be appropriately resourced.

For a detailed socio-legal evaluation of different aspects of the Intervention see “Law in Context - Indigenous Australians and the Commonwealth Intervention”.