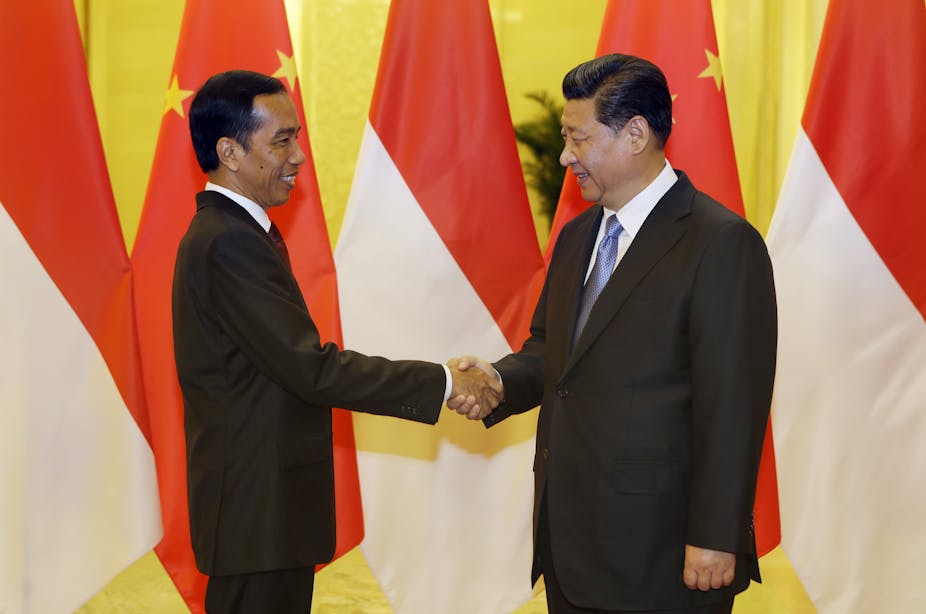

With his country’s economy in mind, Indonesian president Joko Widodo is reciprocating China’s invitation to build stronger relations.

China has been actively inviting southeast Asia’s largest economy to strengthen relations. Following the inauguration of Widodo, who is commonly known as Jokowi, and just days before the APEC Summit in Beijing, Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi visited Jakarta.

For China, Indonesia will be an important partner to manage its relations with countries in the southeast Asia region, grouped in ASEAN. China is involved in territorial disputes with several ASEAN members over the South China Sea.

For Indonesia, China can be a source of finance for infrastructure projects in the archipelago. Indonesia needs around Rp 6,000 trillion (or around US$740 billion) for infrastructure development projects in the next five years to achieve 7%-a-year growth in its economy. Indonesia is currently experiencing its slowest growth since late 2009. The government expects 5.8% growth this year, lower than the 6.3% target.

At the APEC Summit in Beijing, Jokowi requested that Chinese president Xi Jinping boost the involvement of Chinese state companies in developing Indonesia’s infrastructure. He also proposed a bigger role for Indonesia in the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). He suggested the headquarters of the AIIB be in Indonesia.

Some analysts view AIIB as a rival to the Japan-backed Asian Development Bank and thus a driver of change in the US-Japan-dominated status quo in the Asia Pacific. Australia, under pressure from the US, is not joining the AIIB.

What do Indonesia’s closer economic relations with China say about Indonesia’s relationship with the US and its allies?

More China and (not) less America

Indonesia’s intention to forge closer ties with Beijing is a natural result of China’s economic rise. It does not, however, reflect the demise of US and its allies’ influence in the region. In contrast, by getting closer to China, Indonesia is inviting balancing acts by US and its allies. By doing so, Jakarta is hoping to broaden its options in various policy arenas.

China is the world’s second-largest economy. Within a decade or two, it is expected to grow into the world’s largest.

Most countries in southeast Asia and beyond want to reap the benefits of China’s rise. But they don’t want to be dominated by a powerful bully. Despite Chinese rhetoric of a “peaceful rise”, its actions are not always peaceful – as seen in recent incidents in the South China Sea.

Even so, ASEAN countries could not resist their big northern neighbour. Vietnam, for example, benefits from trading with China. Trade between Vietnam and China increased tenfold from US$1.2 billion in 2001 to around US$12 billion in the late 2000s.

To balance China’s power, Vietnam joined the US-backed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) discussions. This move allows Vietnam to diversify its economic relations and gain access to a powerful ally.

It should be noted, though, that at the APEC Summit China pushed for the formation of the Free Trade Area in the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP). Many interpret this move as China’s attempt to “neutralise” the exclusionary effect of the US-backed TPP. China is excluded from the TPP.

Foreign policy based on national interest

Jokowi has signalled that his foreign policy will be guided by Indonesia’s economic national interest. Consequently, his international relations achievements would be measured by tangible results. This is why Indonesia is getting close with China, but the process will not be without obstacles.

At least three issues will guide Indonesia’s policy towards China. First, Indonesia wants to have more balanced trade with China. Since the 2000s, Indonesia has experienced growing trade deficits. In 2008, Indonesia recorded a trade deficit of US$3.6 billion. The deficit is growing and reached US$7.7 billion in 2012.

Second, Indonesia wants to access funds from the huge Chinese economy to develop its infrastructure. Jokowi’s speeches at the APEC and ASEAN summits illustrated this. At APEC, he elaborated on Indonesia’s development plan and invited APEC economies to invest in infrastructure projects in the country.

China has the economic capacity to provide what Indonesia needs. It has the largest foreign-exchange reserves in the world, amounting to US$2.4 trillion.

This does not mean that Indonesia sees the ADB as less important. Currently, the ADB is the third-largest source of financing for Indonesia’s development, with 15.2% of total financing. Japan, the leading actor in the ADB, is the largest (35.1%) and the World Bank is the second-largest (23.6%). So, rather than a sign of allegiance, Indonesia sees participation in the AIIB as an opportunity to expand its options to fund infrastructure development.

Third, ensuring economic growth, stability and security in the region is important. In this context, the conclusion of a code of conduct in the South China Sea will be on the agenda.

Of course, the task of concluding the code of conduct has never been easy. In May, China deployed an oil rig in disputed waters off the coast of Vietnam, provoking anti-Chinese riots there. In August, the Philippines spotted two Chinese hydro-graphic ships in an area claimed by the Philippines as part of its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

With China’s increasing economic clout in the region, reaching agreement might be even more difficult.