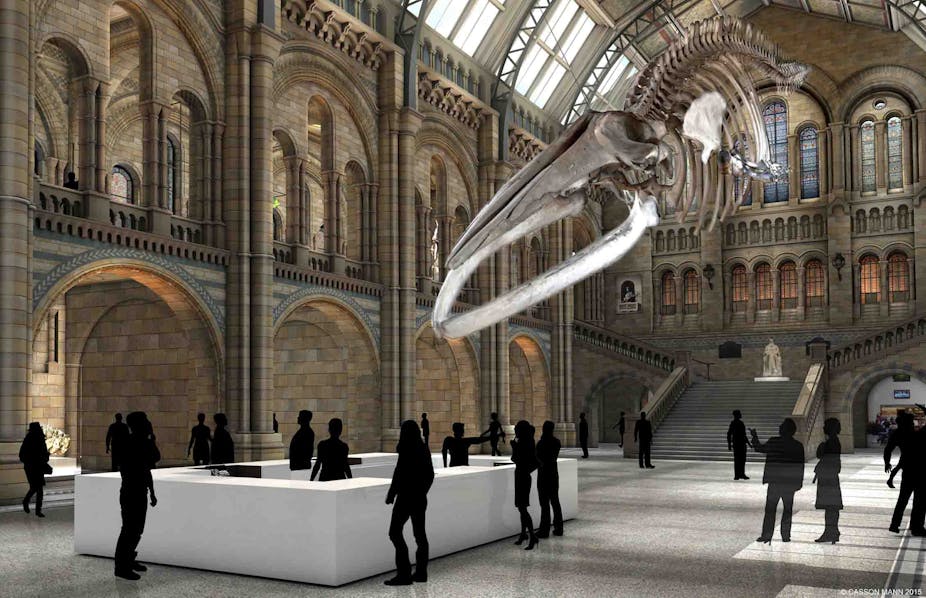

The Natural History Museum’s plan to remove “Dippy”, the cast of a diplodocus skeleton, from its entrance hall, and replace it with a genuine skeleton of a blue whale has been met with outrage. The #savedippy campaign quickly started trending on Twitter.

But Michael Dixon, the museum’s director, claimed the whale would remind visitors of humanity’s duty to the environment and the museum’s conservation work. He also stressed the importance of the “real and authentic”. A copy, even of a dinosaur, cannot compete with an authentic whale.

The Natural History Museum’s blue whale has a venerable history: acquired in 1891, it became the first blue whale skeleton on public display in 1935. But in books, there were whales on display way before this.

In Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), Ishmael defends his detailed knowledge of sperm whale anatomy by explaining that he was shown a real skeleton by King Tranquo of the Arsacides. Tranquo exhibits his sperm whale alongside “whatever rare things the more ingenious of his people could invent”, including “chiselled shells, inlaid spears, costly paddles”, and the “natural wonders” cast on his shores: in other words, in a museum.

Two whales

In 1850s America such authenticity could not necessarily be expected of museums. PT Barnum’s immensely popular American Museum on Broadway enticed visitors with objects of questionable legitimacy, such as a mummified “Fee-jee Mermaid” – the torso and head of a juvenile monkey sewn to half of a fish. Historian James Cook has argued that visitors’ pleasure came from judging – and perhaps debunking – the veracity of Barnum’s curios.

While Ishmael visits the whale skeleton in a temple, a place of reverence, he explains that there is another sperm whale skeleton on display. This whale is owned by a British aristocrat who has articulated the skeleton for the amusement of paying customers:

A footman will show round future visitors with a bunch of keys at his side. Sir Clifford thinks of charging twopence for a peep at the whispering gallery in the spinal column.

Sir Clifford seems to be a reflection of Barnum, charging fees and transforming the whale’s body into an entertainment. His commercial enterprise is in danger of debasing what it displays. Melville sets up a debate between good museums – spaces for the reverence of authentic objects – and bad ones where objects are exploited for entertainment and cash.

But of course, the Natural History Museum is a different kettle of fish. It is free to visit and unlikely to turn its whale into a whispering gallery – so it remains on the virtuous side of Melville’s debate.

Authentic what?

Except, Tranquo’s real whale skeleton in its temple is not without problems. Although Ishmael can take accurate measurements of the skeleton, he is forced to confess that “the skeleton of the whale is by no means the mould of his invested form”. So this is a real whale, but not an authentic experience. “Only on the profound unbounded sea, can the fully invested whale be truly and livingly found out,” Ishmael concludes. Melville is clear that the real and the authentic are not necessarily one and the same: real objects do not necessarily lead to authentic experiences.

Curiously, this point is also made by the “Save Dippy” campaign, led by children’s author, James Mayhew. Mayhew says that the whale skeleton is “hard to decipher”, suggesting it will not provoke the same experience of awe as does Dippy, who has a “clear, recognisable shape”.

So perhaps a real whale isn’t any more authentic than a dinosaur cast. Many even see moving the real whale to the entrance hall as an attack on the authentic experience of the museum. Dixon’s desire that the entrance tells a story that is relevant to the Natural History Museum’s current role rubs up against a strong feeling among the public that the museum must keep telling the story of their own first visits. We want museums to not only be repositories for history, but for our own histories as visitors, and especially our childhoods.

This function of museums is poignantly demonstrated by another cultural depiction of a museum whale. In Noah Baumbach’s acclaimed film The Squid and the Whale (2005), Walt, a teenage boy, comes to realise the roles his parents played in his upbringing while revisiting the model of a giant squid and giant whale in combat at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. This is even more unreal than the cast of Dippy as it confects a hypothetical encounter between the two creatures. Yet it becomes a scene of both authentic experience and a regression to childhood.

Ultimately, this may be the authenticity we want from museums, rather than the display of real objects. Even Melville notes that some bones from Tranquo’s whale had been stolen by children to play marbles with: “Thus we see how that the spine of even the hugest of living things tapers off at last into simple child’s play.”