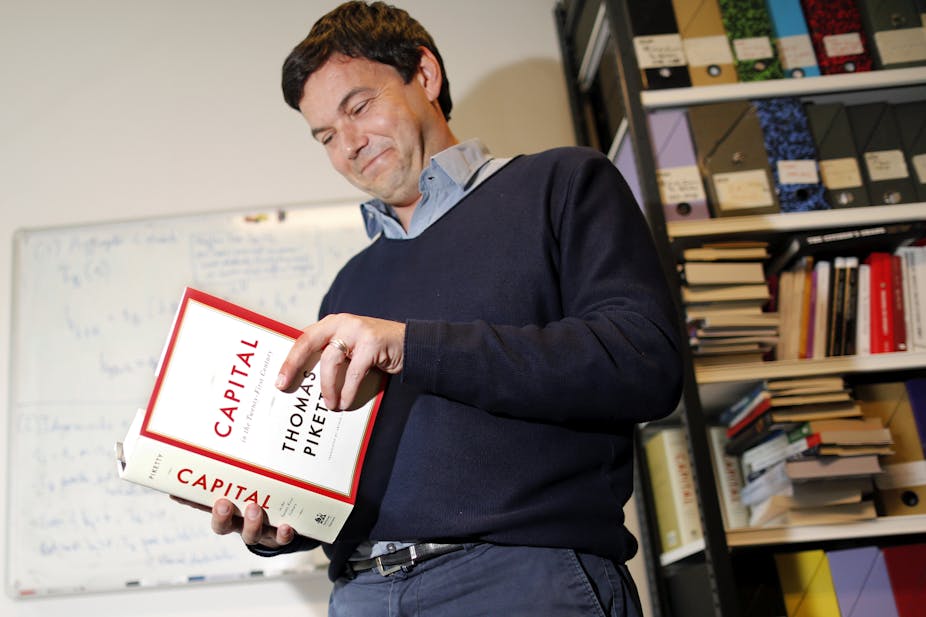

Amid the astonishing list of accolades collected by Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” the book is often also said to be one of the most unread bestsellers. Is this true, and does it matter?

No, it’s not true, or at least the person who made up the story never claimed it was. Rather, the dubious award came with a disclaimer:

This is not remotely scientific and is for entertainment purposes only!

Somewhere along the line the joke was lost, or became a different kind of joke.

The story was created by Jordan Ellenberg in the Wall Street Journal about two years ago. As a lark, Ellenberg, an American mathematician, invented the “Hawking Index” (HI). The index was so-named after Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time, which has sold more than 10 million copies and is widely referred to as “the most unread book of all time”.

To work out the HI, Ellenberg used the “Popular Highlights” feature in Amazon’s Kindle reader, which lists the five most frequently highlighted passages in a book. He assumed that the highlights of books read to the end would be scattered throughout the text. If people didn’t get past the first chapter, the highlights would be clustered at the beginning. To arrive at the HI, the page numbers of a book’s top five highlights were averaged, and then divided by the number of pages in the book. The higher the number, he assumed, the more that was read.

Ellenberg found that the most read bestseller was Donna Tartts’ The Goldfinch, since all five of the top highlights were from the last 20 pages, giving a completion score of 98.5%. The story about Piketty’s tome was born of the fact that nothing was highlighted beyond page 26, giving a score of 2.6%.

The less than scientific rigour was tipped by the 28.3% score given to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, just pipping the 25.9 given to E. L. James’ Fifty Shades of Grey. If most people cannot get through either a 170 page classic novel or 500-odd pages of smut, something is awry with the reading public, or the HI is not what it pretended to be.

Sampling issues aside, the main problem is that the index doesn’t tell of the most read books, but where people mark them up, from which Ellenberg has drawn a questionable inference. A safer assumption is that the index will reveal a book’s most striking or useful passages. As Ellenberg noted, Tartt’s high score arose from mark-ups where the narrative falls away to spell out the book’s themes. In The Great Gatsby, readers tend to highlight a Nick Carraway line about a third of the way into the text that forms “the axis around which the novel spins”. In Fifty Shades, readers (apparently) mark-up the names of the Operas mentioned for followup.

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the first 26 pages encapsulate the rationale and results of the work. Typical of a scholarly book, it begins with a thesis and the balance contains the supporting argument and evidence. The distillation is bound to be the most marked up, no matter how much is read. Indeed, once you get the gist, you can dip or browse for more profit in any number of reading strategies.

If the HI could be retrospectively applied to E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class, it would always fall on the famous preface. The result would be a lower score than Capital in the Twenty-First Century for what is probably the most cited history book of the last century.

Don’t be put off

The HI was pitched as entertainment, and the most entertained of all is probably Ellenberg. Does it matter? Not to the author, I imagine. With sales now exceeding 2.5 million worldwide, even if the HI was what is purported, a score of 2.4% would give 60,000 completed reads in a trade where publishers can only count on sales of about 300 copies.

The unfortunate consequence would be if people are put off. A 700-page book of economics is never going to be a walk in the park, but Piketty’s style is at the lucid end. As I noted in a full-scale review, one of the book’s charms is the way that the author illustrates the changing social consciousness of inequality with contemporaneous novels and television.

Unlike the US, France and the UK, Piketty’s book hasn’t appeared in Australia’s bestselling lists. As the new report on wealth inequality that Frank Stilwell and I prepared for the Evatt Foundation shows, this is not due to a lack of relevance. If it’s because Australians fall for Ellenberg’s canard, the joke will end up on 99% of us.