In the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic the crises of tomorrow can fester. A resurgence of Islamic State (IS) is likely to be one of them.

In recent weeks, IS has carried out a spate of attacks on security forces in Iraq and different areas of Syria. There are striking similarities between these current developments and events that happened in 2013-14 as IS seized huge swathes of territory in Iraq and Syria.

The threat of a resurgent IS is mounting and governments around the world could be about to make the same mistake again of missing it and reacting too late. Based on my ongoing research investigating why the rise of IS in 2013 came as a strategic surprise to European governments, I’ve identified the seven most eye-catching parallels between 2013 and today.

1. Declared dead prematurely

After the death of Osama Bin Laden in 2011, the various branches of al-Qaida in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, Yemen, the Horn of Africa, and the Sahel and Maghreb refocused more locally. The remaining leadership directly addressed grievances against their respective local governments. Al-Qaida seemed to be on the defensive and leaders in Europe and the US expected it to stop posing a national threat.

Similarly to today, it was misleading to hope that IS would decline after its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was killed in October 2019 in a US special forces raid. Like when it emerged out of al-Qaida in Iraq, IS might very well resurge under its new leader, Amir Mohammed Abdul Rahman al-Mawli al-Salbi.

Read more: Al-Baghdadi's death: the rise and fall of the leader of Islamic State

2. Risk of prison breaks

One of IS’s most successful operations was its 2012-13 prison escape campaign Breaking the Walls to free veteran fighters. The campaign was remarkable due to its length and level of organisation, including the major break of Abu Ghraib, Iraq in July 2013 in which more than 500 prisoners escaped.

The IS prisons in northern Syria are currently run by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the primarily Kurdish militia that defeated IS with the support of the west. Overcrowded and understaffed, the SDF has called these prisons a ticking time bomb.

According to Iraqi intelligence, IS has been preparing a prison break campaign, which it calls Break Down the Fences. A systematic prison break campaign similar to Breaking the Walls could pave the way for a resurgence of IS in Iraq and Syria.

3. Car bombs and insurgency attacks

In 2013 more than 8,000 Iraqis were killed by IS, mainly through choreographed suicide bombings. Today, IS is again launching increasingly sophisticated insurgent attacks in Syria and Iraq. This type of violence might be a prelude to a more forceful military return of IS in northern Iraq.

Concentrated in areas beyond the reach of Iraqi and Kurdish security forces, in January a UN report warned that IS is preparing for a steady and gradual return.

4. Western fatigue

The coalition against IS proclaimed that the group had been defeated in March 2019 when it liberated Baghuz, the last city under control of the group. Should IS surge again, the coalition’s efforts would have been in vain. Military action would have to be continued, the SDF further reinforced, and the Iraqi security forces strengthened – not what western governments were hoping for.

In 2013, US and UK public opinion was very negative about the Iraq war, which was largely considered a failure. This resulting “war fatigue” and the desire to militarily leave the Middle East affected the UK’s decision not to intervene in Syria in 2013.

Today’s politicians are wary of contributing resources once again to the fight against this never-ending Jihadi whack-a-mole. The Iraqi parliament’s non-binding resolution to expel US troops after the American assassination of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani in January has added another layer of complication.

5. Risk of a power vacuum in Iraq

In a difference to 2013, the highly polarised sectarian divide between Sunnis and Shias in Iraq – one of the root causes of IS’s appeal to frustrated Iraqi Sunnis – seems to have faded. Yet, Iraq still has a very fragile government and a newly designated prime minister, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, who faces huge challenges.

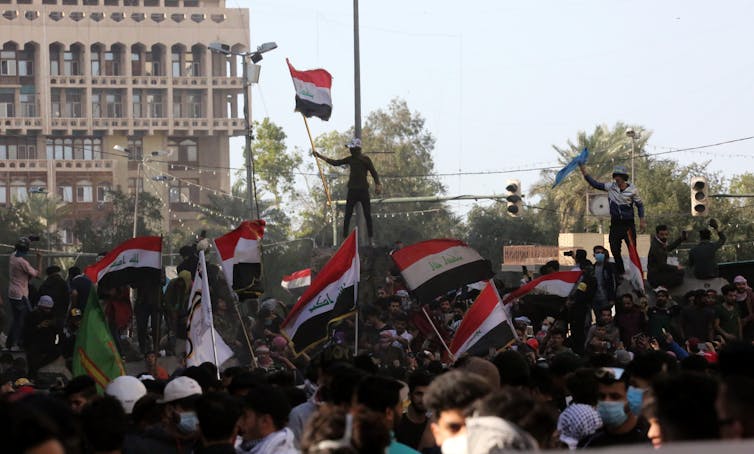

For the time being the government is holding, although further protests like those which began in October 2019, a lack of reforms, and a weakening economy might destabilise the country. Another round of chaos caused by a collapsing government would quickly be exploited by IS to recruit disenchanted citizens.

6. Risk of a power vacuum in Syria

One element that helped IS gain strength in 2013-14 was the ongoing war in Syria, which created a power vacuum that was filled by IS. Other factors that contributed to the group’s success included the departure of US troops from Iraq in late 2011; and Turkey’s subsequent policy to relax its border controls with Syria, which allowed foreign fighters to join IS.

Today, the Syrian civil war and foreign actors might facilitate an IS revival. American disengagement from northern Syria and Turkey’s military campaign in the country that started in October 2019 forced the SDF to redirect its forces towards the north-east. The SDF therefore has fewer resources to devote to the sustained efforts that are needed to prevent IS from resurging.

In early March 2020, a Turkish-Russian deal was concluded, which among others agreed to stop the fighting in Idlib in Syria’s north west. Yet, given the strategic and symbolic importance of Idlib for those involved in the conflict, experts fear that the deal might not last.

Meanwhile, the SDF’s redeployment of forces to defend Kurdish regions against the Turkish incursion has already opened the door for IS to regain footholds in the Deir Ezzor area, IS’s last stronghold before its territorial defeat in March 2019.

7. Foreign fighters and a global presence

In 2013 and 2014, IS was able to attract large numbers of foreign fighters, at the time estimated at 11,000 from 74 nations.

While the flow of foreign fighters coming to Iraq and Syria has now nearly halted, IS still maintains a strong propaganda machinery. Groups around the world have kept affiliations with IS, such as in west Africa and south-east Asia, and IS still has the capacity to prepare or inspire terrorist attacks around the world.

Given these elements, it seems highly probable that IS will regroup, gain territories, and pose a global threat once again. With coronavirus now clouding the picture, governments around the world have neither payed attention, nor devoted enough resources to prevent a possible IS surge.

The international community would be wise to learn from 2013 and tackle each of these different warning signals now. Addressing them individually is much more feasible and could prevent IS from rising again.