For people who would like to learn more about Islam, The Conversation is publishing a series of articles, available on our website or as six emails delivered every other day, written by Senior Religion and Ethics Editor Kalpana Jain. Over the past few years she has commissioned dozens of articles on Islam written by academics. These articles draw from that archive and have been checked for accuracy by religion scholars.

In the previous installment of this series, you learned about the different Muslim sects and the interesting ways they mix in the United States. This article will take you through the historical contributions of Islam and its influence on other faiths across geographical regions.

Your understanding of Islam is perhaps incomplete without a deeper appreciation of its cultural and intellectual history. History books in the U.S. can give an incomplete picture about the richness of its past, so many students may fail to appreciate the importance of this history.

Islamic scholars contributed to early developments in astronomy, medicine and mathematics. Their work was crucial to Renaissance scientists who built on some of the existing scholarship.

For example, the 11th-century astronomer al-Qabisi, one in a line of famous Islamic astronomers, helped formulate a critique of the then-prevalent notion that the Earth was at the center of the universe. As scholar of Middle Eastern studies Stephennie Mulder writes, that model later informed the view of Nicholas Copernicus, a Renaissance astronomer.

Important works of mathematics were written by Islamic scholars, including substantial contributions to algebra and a commentary on the fourth-century B.C. Greek mathematician Euclid that was later translated into Latin. An early description of surgery to remove cataracts was written by Islamic ophthalmologists in the year 1010.

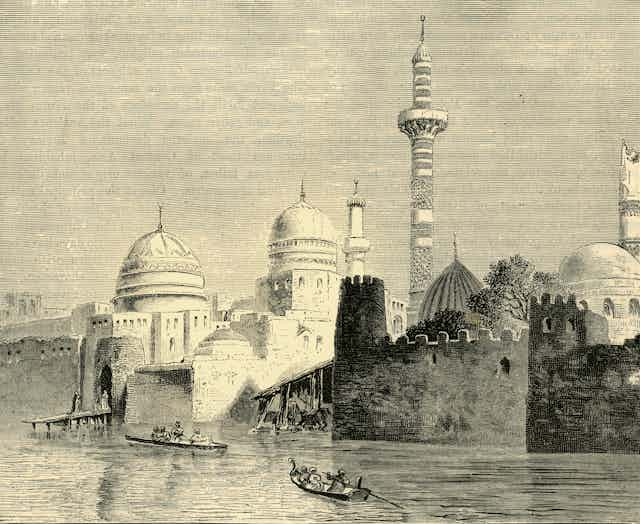

Many of these scholars were based in Mosul in modern-day Iraq, a city that was occupied by the Islamic State from 2014 to 2017. Mosul was a key center on the Silk Road – a network of trade routes – which also contributed to its rich diversity of people and traditions. As Mulder notes, “The city was home to a diverse group of people: Arabs and Kurds, Yazidis, Jews and Christians, Sunnis and Shiites, Sufis and dozens of saints holy to many faiths.”

Among the Islamic State’s destruction of architectural sites in Mosul was the tomb of the Prophet Jonah, a figure revered by all three Abrahamic faiths. Jews venerate Jonah as a symbol of repentance. In the Islamic faith, Jonah, also known as Yūnus, is seen to be an exemplary model for human behavior. In the Christian faith, Jonah’s story appears in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke.

Influence of Islam was seen in the cultural history of many countries. Scholar Kishwar Rizvi explains that in medieval Spain, for example, the troubadour poets who were known for their lyrical poetry “borrowed their lyrical beauty from Arabic.” Until the 15th century, as Rizvi says, Arabic was the courtly language of southern Spain.

The exchange between Islam and other Abrahamic faiths extended to architecture. The famous 12th-century Palatine Chapel in Sicily takes some of its architectural style from the Fatimids, the Shiite rulers of Egypt between the 10th and 12th centuries.

“Such exchanges were common, thanks to the mobility of people as well as ideas,” writes Rizvi.

Understanding the rich history of Islamic art can help counter many presumptions about Islam today. In explaining how different religious views were accommodated within Islam, scholar Ana Silkatcheva points to a 19th-century tile from Iran depicting a crucified Jesus surrounded by the Twelve Apostles.

“In Islamic understanding, Jesus was a prophet, granted the same respect as Muhammad, but did not die on the cross,” Silkatcheva said. “This is evidently a tile made for or by the Christian community in Persia under Islamic rule.”

Art history can be revealing to many Muslims as well. For most Muslims, the depiction of the Prophet Muhammad is considered to be forbidden. However, Silkatcheva writes about a 17th-century manuscript folio that depicts the prophet, suggesting that visual depictions of the prophet were acceptable in the past.

Rizvi offers a reminder from the poetry of 13th-century Muslim mystic Rumi that sums up this belief in peaceful coexistence:

“All religions, all this singing, one song. The differences are just illusion and vanity.”

This article was reviewed for accuracy by Jessica Marglin, Associate Professor of Religion at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences.

Fact: The Dutch painter Rembrandt collected miniature paintings from the Mughals, a Muslim dynasty that ruled the Indian subcontinent for over 300 years. Silks from the Safavid empire (the Iranian dynasty from the 16th to 18th century) were so popular that Polish kings had their coats of arms woven in Isfahan. – From an article written by Kishwar Rizvi, Professor of Islamic Art and Architecture at Yale University.

In the next issue: Why women wear the headscarf

You can read all six articles in this Understanding Islam series on TheConversation.com, or we can deliver them straight to your inbox if you sign up for our email newsletter course.

Articles from The Conversation in this edition:**

Further Reading and Resources:

“The Shrines of the ‘Alids in Medieval Syria: Sunnis, Shi'is and the Architecture of Coexistence,” by Stephennie Mulder: Scholar Stephennie Mulder’s book on Islamic architecture goes beyond Islam’s sectarian history to reveal a past marked by cooperation and accommodation.

“Close Encounters in Medieval Provence: Spain’s Role in the Birth of Troubadour Poetry,” by María Rosa Menocal.

“Mathematics and Islamic Art,” by Lesley Jones: Jones’ journal articles explores Islamic mathematics’ influences in art.

“How Islam changed medicine,” by Azeem Majeed, professor of primary care at Imperial College Faculty of Medicine in London.