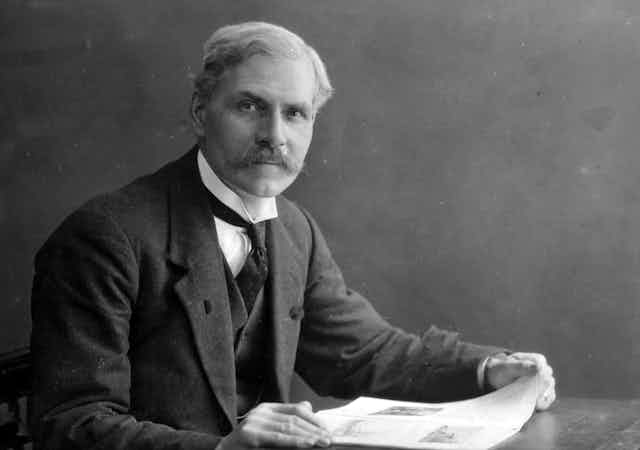

There was a time when to ridicule – or condemn – the Labour leader of the day, a newspaper cartoonist needed only to append under their subject’s nose a luxuriant moustache. That was all that was necessary to suggest that whoever they were drawing was the “new Ramsay MacDonald”.

Writers needed only prefix the word “Mac” to the leader’s name with the same in mind. Popular memory is finite, however. “Keir MacStarmer” would be meaningless.

The Labour leader would nevertheless prefer for people not to draw comparisons with Macdonald, tempting though this may be in the year that marks a century since MacDonald became Labour’s first prime minister. There was a reason Starmer’s parents named him Keir, and not Ramsay.

Keir Hardie was the saintly founder of the party, almost too principled for power. Ramsay Macdonald was the man who betrayed the party he helped to found.

The first Labour government didn’t survive 1924, and the next, in 1929, MacDonald crashed after two years by joining the Conservatives in a national government. Economic crisis was his justification. But for many in the party he had abandonded, personal weakness on the part of the man Winston Churchill dubbed the “boneless wonder” was a better explanation.

History doesn’t repeat but it can rhyme

One parallel that can be drawn between MacDonald’s Labour and Starmer’s is inexperience. In 1924, only a few Labour ministers – Arthur Henderson and J. R. Clynes – had been in government before, six years previously in the Lloyd George coalition. Those with ministerial experience who may assume office in 2024 – such as Yvette Cooper and Hillary Benn (whose grandfather was in MacDonald’s cabinet) – will have been excluded from power for 14 years.

In the event of a Labour win in 2024, Starmer, like MacDonald, will have being prime minister as his very first experience in government. That is unusual, though less so recently: neither Tony Blair nor David Cameron had held any office before they held the highest of them all.

But Blair and Cameron also left office younger than MacDonald was and Starmer would be on assuming it. Becoming prime minister in their sixties meant that they had a past – the Conservatives aim to tar Starmer with his, as they did with MacDonald a century before.

Ramsay Mac had been prominently anti-war during a period of lustful militarism. Though he was not a communist, his opponents found it easy to imply an association with what was then regarded as an existential threat to the realm.

For those who wish to see it, therein lies peril: Starmer, for all his protestations that his was a working class background is also “Sir Keir”, the metropolitan barrister. Labour lore has it that McDonald all-too gladly accepted the aristocratic embrace when he went into government with the Tories, abandoning the working classes. At the following election Labour was smashed, and out of office – for 14 years.

With little else to hand, the Conservatives will seek to capitalise. No more provocative occupation could be wished for in red wall leafleting than “human rights lawyer”. A deep and raking dive into Starmer’s casework as a lawyer has already begun by today’s tabloids, and an attempt to sow the seeds of a conspiracy theory already made in groundless claims about his role in the CPS decision to drop the case against sex offender Jimmy Savile.

In 1924, the tabloid press sought to do similar with MacDonald, hoping to thwart his rise to the premiership by falsely associating him with Bolshevik politician Grigory Zinoviev.

Different times

The circumstances around the election that brought Labour to power in 1924 could hardly be more different from those that could do so in 2024, however. Conservative prime minister Stanley Baldwin, who had been elevated to the premiership without an election in 1923, did something Theresa May, also elevated to the premiership without an election, emulated in 2017.

He went to the country within a year of taking office, years earlier than he needed to, and lost his majority. May also called an election, narrowly won government again and was out within a couple of years.

Baldwin’s decision has puzzled historians (May’s was merely a mistake). One interpretation is that he most feared his era’s Boris Johnson: David Lloyd George. It was thought that the best way to ‘dish’ the dishonest, dynamic, divisive leader of the Liberals was for Labour to replace his party as the second party of government.

Another interpretation is that Baldwin felt it best to give the working classes a taste of power – to house-train Labour. With the kind of accommodation the British ruling classes usually displayed when faced with potentially uncontrollable threats, they acceded to sharing power – and maintained most of their privileges.

But today, Starmer has the most powerful of all campaigning messages: “time for a change”. Fourteen years of power is usually deemed enough for any party, and that’s without what even the government’s supporters would concede as being the chaos of the latter half of it.

Nevertheless the Labour prospectus of 2024 – to the chagrin of those to the left of the party, and to the fear of those to the right – is characterised by moderation. To reach Downing Street for the first time in 1924, Labour had to overcome the public perception that it was extreme. Imagined though that perception might have been, it was potent. After all, no one knew what a Labour government might be like.

Labour in 2024 has to overcome imagined histories – the idea that Labour governments always lead to crises. The Conservatives, and their print and broadcast proxies, will seek to ensure that voters have a very certain sense of what Labour governments are like. And they may privately maintain what looks like an increasingly overoptimistic hope that no Labour leader named Keir should ever win power.