Antibiotics started out as the biggest medical breakthrough of the 20th century but overuse in humans and animals has led to resistance and reduced efficacy.

We’re now at risk of reverting back to a pre-antibiotic era, with people dying from what should be easily-treatable infections.

Overuse of antibiotics

Antibiotic resistance develops as a direct result of the use and overuse of antibiotics. The more antibiotics are used, the more resistance that eventually develops.

This is why when antibiotics are used when there isn’t a bacterial infection present (such as a viral sore throat), we get all the harm and none of the benefit.

In this case, all the bacteria in our body are exposed to that antibiotic and we run the risk of developing resistant bacteria. If we already have resistant bacteria in our body, they can grow to very high levels.

When you consider the huge volumes of antibiotics used in the world, this is a major problem.

Antibiotics are often given to people when they are of little or no benefit. In fact, over half of all antibiotics administered in hospitals and in the community aren’t needed.

In many developing countries antibiotics are available over the counter without prescription.

But medicine isn’t our biggest problem. Two-thirds of all antibiotics are not even used in people but in the agricultural sector, particularly in food animals.

These antibiotics are used as mass prophylaxis and to promote growth. This is not only inappropriate and irresponsible, it barely delivers any economic benefits and serves no benefit to the animals.

Outside Australia, last resort drugs such as third generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones are widely used in agriculture, causing superbugs to needlessly enter food supplies.

In countries with poor water supplies, resistant bacteria from people or animals can infiltrate the water supply then recycle back to both people and animals who then get more antibiotics – this makes the whole vicious cycle worse and worse.

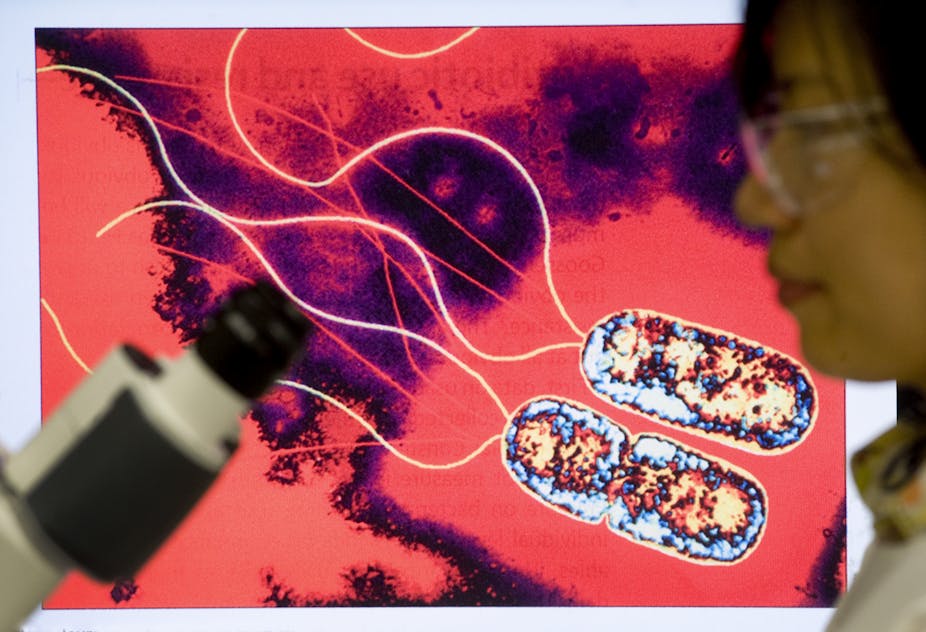

Superbugs

Superbugs are bacteria that are resistant to most, and in some cases all, antibiotics. This means that previously powerful antibiotics no longer kill common bacteria.

These superbugs have effectively put on bullet-proof vests against our “magic bullets” (antibiotics) that cured people with serious infections.

Superbugs are not necessarily more powerful bugs but they are able to resist the effects of the antibiotics we direct against them.

They work by either destroying the drug or altering the “goal posts” by changing the receptors where these drugs need to bind and act.

Beyond antibiotics

In the 1920s pre-antibiotic era, 80% of people who contracted Golden Staph blood stream infections died.

This death rate has been markedly decreased with the use of effective antibiotics. But now we find many strains of Golden Staph are difficult or sometimes impossible to treat.

More importantly, even more common germs such as E. coli (that causes blood stream infections and urinary tract infections) are frequently difficult or impossible to treat.

In the developing world more than half of the infections caused by these common bacteria are now untreatable.

We have no effective antibiotics available except one class of carbapenems or “drugs of last resort” which need to be given by injection and are so expensive that the majority of the population can’t afford them.

For a lot of people, particularly in developing countries, the future is bleak.

The worst case for antibiotic resistance is that we will have more and more common bacterial infections that are difficult or impossible to treat.

In the short-term in countries like Australia, it may mean we can’t use oral therapy but need intravenous therapy.

The very worse scenario is when nothing works. That means that individuals with infections are in danger of dying or having a much longer and prolonged illness.

It also means many of the procedures we take for granted in modern medicine such as bowel surgery and transplants will not be possible because bacterial complications are so common in these procedures.

If we don’t have antibiotics that work, the risk of infection and death will make these operations unviable.

Reducing the threat

There is a lot we can do however to improve the situation.

Australia is relatively lucky. We have low levels of resistance compared to most other countries in the world due to restrictions on antibiotic prescribing.

We don’t import meats and foods with “superbugs” and have better controls on which types of antibiotics are used in food animals here.

But we can always do a lot more.

We need massive decreases in the total amount of antibiotics used around the world in both the human health and the agricultural sector.

Any restrictions need to ensure that people who really need them can get hold of them. But those who don’t need these broad spectrum antibiotics should only have access to a narrower spectrum of antibiotics.

Antibiotics of last resort should be banned in food production or limited to single animal use by injection given by the prescribing veterinarian themselves.

Restricting antibiotic use in hospitals, the community and meat production must be a world-wide effort.

And because access to a safe and reliable water supply is also an essential part of any solution, the effort needs to be taken much more seriously.