COVID-19 times have brought sober realisations about deep shifts in Australian society. Encroaching steadily over the past half-century, these have been largely submerged from daily view, until now.

Decades of cumulative attacks on the public sector have made privatisation and contracting out an unthinking government reflex. This includes areas the pandemic has revealed as highly unsuitable, including aged care and quarantine security.

Workplace deregulation has gone hand in hand with an enormous rise in casualisation. The pandemic has highlighted how many workers stitch together jobs at multiple workplaces to earn enough to survive, multiplying the chances of community COVID-19 transmission.

Denied the paid sick leave enjoyed by people in permanent jobs, casuals have to keep working, healthy or not. Precarity has turned out to be flexibility’s flipside, with unequivocally bad consequences for public health.

Women are more affected

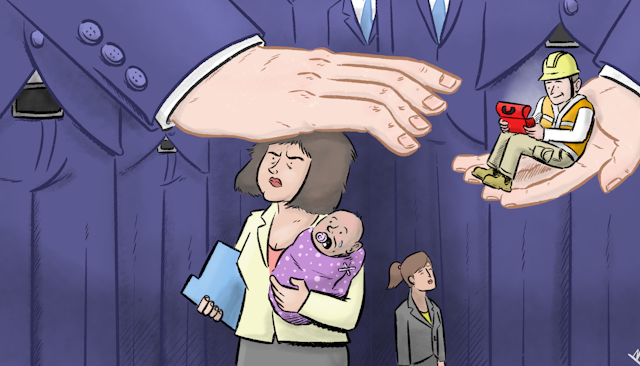

The pandemic’s gendered impact has been especially stark. Under pressure, dynamics many people thought were in deep retreat visibly sprang back into action.

More likely to occupy low-paid, precarious jobs than men, women suffered first and disproportionately from pandemic job losses.

During lockdown, domestic violence — mostly committed by men against women — has spiked, and is even more difficult to escape than usual.

Read more: Coronavirus and 'domestic terrorism': how to stop family violence under lockdown

Women perform the vast share of lockdown-driven homeschooling, compounding their pre-pandemic burden of an unfairly large share of domestic labour generally.

The Morrison government provided free childcare early in the emergency, giving many families their first experience of relief from worry around this fraught aspect of family life. But it was snatched away again in the government’s first act of pandemic policy rollback. This doubly impacted on women as workers as well as parents, given the overwhelming bulk of childcare employees are female.

In contrast, many businesses received massive handouts with, it emerged later, highly variable flow-on to the workers the handouts were supposed to keep in their jobs. With little accountability attached to the government assistance, some employers were accused of outright rorting it. The contrast with tight accountability provisions attached to government welfare for individuals who need help is stark.

Further, the Morrison government’s positive job initiatives, such as they are, favour men, with job-creation plans focused on male-dominated industries.

Good morning, ma'am, is your husband home?

That this approach is based on, and reinforces, the idea of men as primary breadwinners is barely disguised. This is despite the fact women can be – and are in large numbers – primary breadwinners too and deserve the same opportunities.

Even the government’s tax cut bring-forward mooted for the October budget is heavily gendered: men are set to get more than twice the benefit women receive on average from the tax cuts, according to Australia Institute modelling.

One unequivocal boon of the pandemic has been the widespread, high-quality analysis and reporting of its gendered impacts.

Equally striking has been the expectation among many of these analyses’ authors that their findings would make the Morrison government change course, on the assumption that either the government did not realise its policies’ gendered impacts or because it would be shamed into adjusting them once these were revealed.

If you want to understand a government’s priorities, look at where it puts its money. The Morrison government is not just indifferent to the gendered impacts of COVID-19. The pattern of its pandemic policy decision-making suggests an active if not explicit “men first, women and children second” approach.

This is disappointing but not unexpected, given the male dominance of the Liberal and National parties’ federal parliamentary ranks: 73.2% of Morrison government MPs are men. Let that sink in for a moment. Only one in four federal Coalition MPs is a woman.

Around the Morrison government cabinet table the picture is the same: 73.9% of LNP cabinet ministers are men. There are just six women in the 23-person cabinet.

In the House of Representatives, from which the prime minister is drawn and where policy must initially be fought for and won to have the chance of being turned into law, 80% of Morrison government MPs are men. Again, it is worth pausing to reflect on this: four out of every five lower house LNP politicians is a man.

A ‘men first’ approach to the pandemic

It is not such a surprise, then, that the government pursues “men first” policies.

While some – perhaps many – LNP women may support this stance, a reasonable assumption is that fairer shares of parliamentary LNP seats for women would redress this skewed approach at least somewhat.

Anyone supporting fair shares for men and women in life’s burdens and benefits would surely support fair shares for men and women in terms of parliamentary power.

The Australian Labor Party long ago faced up to and solved this problem with an initially controversial, now unremarked upon, preselection quota system for winnable seats.

Today men and women are almost equally represented in the federal Labor caucus: a bare majority (52.1%) of federal Labor MPs are men.

In contrast, the Liberal Party in 2016 adopted a ten-year plan without quotas to increase its female representation in federal parliament. It has visibly failed.

The problem has been compounded by the retirement from politics of senior female Liberal ministers like Julie Bishop and Kelly O’Dwyer at the 2019 election, as well as the loss of emerging talent such as businesswoman Julia Banks who resigned from the party in disgust at its sexist culture.

Read more: Quotas are not pretty but they work – Liberal women should insist on them

More than just numbers

Longtime activist for women in politics, Ruth McGowan, says the extra pressures arising from the pandemic could well discourage women who might otherwise have considered a run from doing so. Women’s burgeoning domestic labour burden during the pandemic is likely to literally keep women in the home and away from the House of Representatives, McGowan suggests. To the extent this could further depress women’s share of Coalition seats in parliament, this is very bad news.

A senior cabinet member, Environment Minister Sussan Ley, last year called on the Liberal Party to introduce quotas for women. Her cabinet colleague, Foreign Affairs Minister Marise Payne, said “all options [should be] on the table”, adding she was as yet undecided about quotas. Others, such as Victorian Liberal senator Jane Hume, support a “Liberal alternative” to quotas to address the party’s skewed representation.

The gendered nature and impact of the Morrison government’s pandemic policy responses makes the domination of men within the coalition cabinet and party room a matter of national significance.

The Liberal and National parties’ preselection processes are broken and need fixing. The fact that only one in four coalition MPs in the Morrison government’s cabinet and party room is a woman is proof.

Read more: A 'woman problem'? No, the Liberals have a 'man problem', and they need to fix it

Until the structural sexism within the Liberal and National parties’ ranks is fixed, the Coalition’s “men first” policies will likely continue.

Women and children need the Morrison government’s “senior six” female cabinet ministers to person up and get their parties to adopt quotas for women in winnable Liberal and National party seats. It’s the only thing proven to work and it’s way past time the problem was fixed.