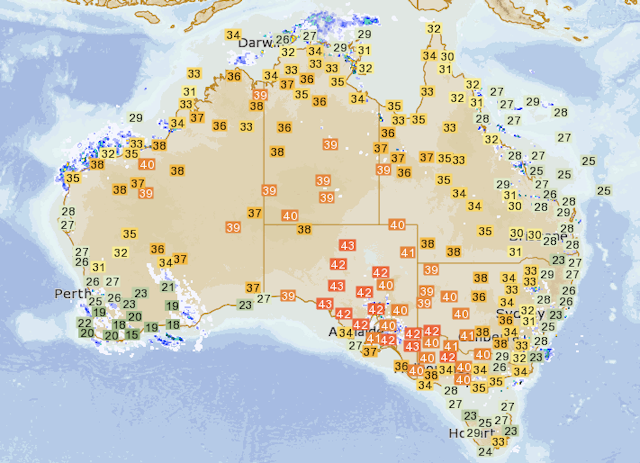

As much of inland and eastern Australia sweats through its first heatwave of the summer, a new interactive website has been launched to track where the heat is coming from and to map past heatwaves across the country.

Extreme heat has killed more Australians than any other natural hazard in the past 200 years. For example, more people died during the 2009 Victorian heatwave than the Black Saturday bushfires.

But as scorcher.org.au explains, a heatwave is more than just one hot day.

It is a long period of excessive heat, with at least three consecutive days where the daily maximum temperature is in the top 10% of warmest temperatures for that calendar date.

Our new website uses daily temperature records that stretch back to 1910.

And research into heatwaves over Australia and the world reveals some concerning trends - particularly when it comes to increasingly frequent and long heatwaves over eastern Australia.

Is it hot enough to be a heatwave?

Australia is no stranger to scorching extreme temperatures. Hot temperature events, including heatwaves, have punctuated our climate for thousands of years, and will continue to do so for thousands of years more.

But what exactly is a heatwave? And although they are a natural part of our climate system, are there any signs of changes in the past century of weather records around Australia?

That’s what Scorcher sets out to explain.

Based on maximum temperature, the website has two main functions: a map that displays where in Australia a heatwave has recently occurred, and clickable links to temperature records for more than 100 weather stations.

It also lists other interesting facts such as the longest heatwave, the hottest heatwave, and the hottest stand-alone day for each weather station.

Beyond one bad day

The universal heatwave definition is a prolonged period of excessively hot weather, which, from a climate perspective, is as ambiguous as it sounds.

My recent research has sought to make this definition clearer. The Scorcher site defines heatwaves based on peer-reviewed and published scientific research, conducted at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science.

Heatwaves occur when at least three days in a row exceed the 90th percentile, where this threshold is unique to each day of the year.

And they can be measured from daily maximum, minimum, or average temperature. Researchers can then analyse them in terms of their frequency, intensity, duration, time of occurrence, and how widespread they are.

A number of hot days need to line up for a heatwave to occur. Sydney’s hottest recorded temperature, for example, was not part of a heatwave.

From Central Australia to Tasmania

We also tend to think of heatwaves as only hitting in summer. When we think of extreme heat, we think of scorching hot days, such as last summer when the mercury soared above 40°C.

But “excessive heat” can occur in the cooler months too. The use of a percentile-based threshold allows us to measure non-summer heatwaves, as well as their warm season cousins. This wouldn’t happen if excessive heat was defined as, say, a number of days over 30°C or 35°C.

Setting an arbitrary threshold also means that heatwaves would be detected too often in some regions (such as in Central Australia), and not enough in others (such as Tasmania).

However, just like heatwaves are relative to the time of year, they are also relative to where they occur. So, heatwaves can (and do) happen in Tasmania, and they can have serious effects, even if they can’t match the searing intensity of a heatwave in Central Australia.

Longer heatwaves, more often

Since the 1950s, parts of Europe, Asia and North America, and Australia have seen a detectable increase in the number of days that have been part of a heatwave. An increase in the number of heatwave days also eventually means we’ve seen longer and more frequent heatwaves.

Changes in heatwave intensity are highly regional, with a tendency towards increasingly frequent and long heatwaves over eastern Australia. That’s been happening more since the early 1970s.

We also need to keep an eye on heatwaves occurring during the cooler seasons. My recent research has shown that the occurrence of these events are increasing faster than summertime heatwaves.

Crops such as fruit, wheat and maize have finite temperature thresholds. The occurrence of these temperatures, particularly in the form of a heatwave during the traditionally cooler growing season, can lead to massive crop failure.

New South Wales recently saw an extremely early start to the bushfire season. This was, at least in part, due to extreme temperatures relative to winter and spring drying out the fuel load, and shortening the delicate hazard-reduction season.

When it comes to extreme temperature, the future is looking pretty bleak.

The recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report states hotter temperatures will occur more often. Heatwaves are no exception.