One of the priorities of the Closing the Gap reporting is that Indigenous cultures and languages are “strong, supported and flourishing”. It also calls for Indigenous students to “achieve their full learning potential”.

These two priorities are listed in totally different sections of the report but they are very much connected.

Schools can play a big role in Indigenous language revitalisation and creating a strong sense of identity and belonging for students, supporting their wellbeing and learning.

Our new research shows how this can be done through co-designing curriculum resources with local communities that privilege local knowledge, strengths, stories and languages.

A repository of language and culture

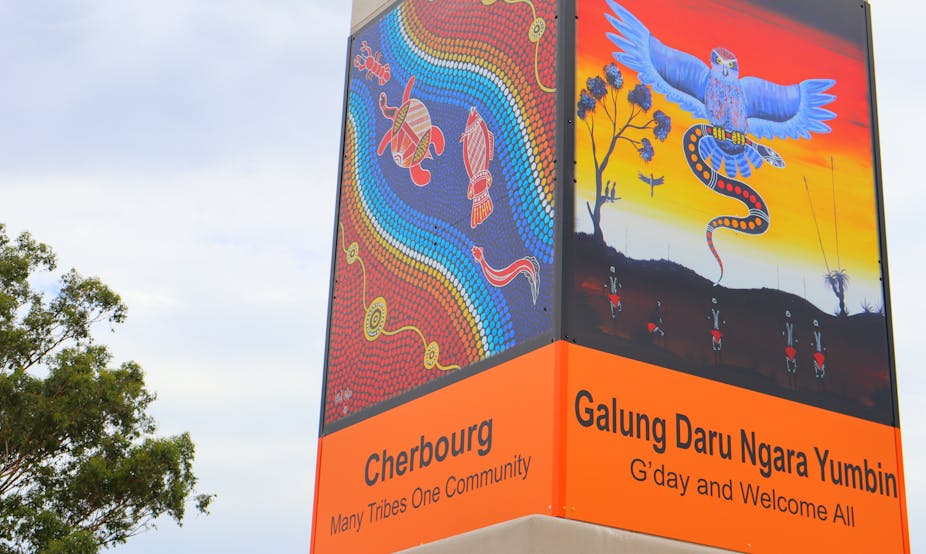

In 2020 we began to work with the Elders advisory group connected to a local high school on Wakka Wakka Country, which covers a vast area in Queensland’s Burnett region. But the communities involved in this project were Cherbourg and Murgon.

This was a co-designed process from the very beginning. This meant we spoke to Elders and the community to identify what they wanted and then worked with them throughout the process.

Talking to Elders, community and school staff, we learned there was a strong desire to have tangible resources about local history and culture that elevated their voices. These could be used by local childcare services and schools, as well as the broader community.

Indigenous authors Anita Heiss and Uncle Boori Monty Pryor delivered a series of workshops with school students and local community members to share their experiences and inspire people to share their stories. We also had local Indigenous researchers working closely with community to support anyone who wanted to contribute a story.

The project culminated in a series of strengths-based stories (emphasising strengths and aspirations) being hosted on the Cherbourg Shire Council website to give the community control of the Binung Ma Na Du (ear, eye, hand and heart) project.

The series includes video stories, written stories, podcasts and bilingual books. For example, the 13 video stories include diverse stories of community members memories of growing up in Cherbourg, overcoming adversity and staying strong in culture. The podcasts continue the theme of storytelling through yarning and understanding the lived experiences of mob from these communities.

All storytellers own the intellectual property of their stories.

Read more: 'Co-design' is the latest buzzword in Indigenous education policy. Does it live up to the hype?

All students benefit

We also asked 28 local people (six non-Indigenous school staff and 22 Indigenous school staff and/ or community members) about what they see as the benefits for students when Indigenous knowledges and languages and embedded in school learning.

All participants were clear there are benefits for all students, whether they are Indigenous or non-Indigenous.

For Indigenous students, strengthening identity and building confidence clearly emerged as key strengths.

As Uncle Edward, a Wakka Wakka Elder, said:

[…] it’s about making our children feel proud – not just of themselves, but of their people, of their ancestors. And that language that they take is part of those old people. And […] and I always say to them, ‘You take that language of the old people, you’re gonna start acting like them old people’. And I think our young people start to do that.

Our respondents noted how non-indigenous students gained greater understanding about cultural differences. Learning language and locally produced stories also helped build relationships between Indigenous and non-indigenous people.

As Lavell, a community member and father, shared:

[…] when I was growing up in high school I did German and it was no use to me as an adult. If they learn Wakka Wakka they learn the language of this place first and they need to learn the language of this place and we need to learn they’re language to come together and live in harmony. We all call Australia home and we need to all respect that.

Lessons from our research

We also asked the group of community members and school practitioners what good co-design looks like in developing local curriculum resources.

They emphasised how collaboration with community needs to be there right at the start and right through to the end of a project. They also stressed that local knowledge and leadership must be incorporated into the final project (so it can’t just be researchers or policymakers making their own findings).

Sarah, a community member and parent shared that:

communities and schools work better together when we acknowledge and value the knowledge holders such as Elders, parents and community.

How can other schools develop similar resources?

For schools who want to work with their local communities to enhance local knowledge and language in their curriculum, here are some key tips, based on our research:

work with Indigenous staff in your school first and foremost to learn about local cultural protocols. If you don’t have any Indigenous staff, your local Elders are the first place to go

ensure this will be reciprocal. Be clear about what and how you are giving back to the community. For example, you might offering a space for regular communication between the school and community (not just a one-off interaction)

work collaboratively with Elders and community to have visual representations of the traditional owners, local language (for example, signage and greetings) and cultures around the school. This is so these become common knowledge among all students and staff and part of the school’s culture

when working with Indigenous people in remote Indigenous communities, ensure you have met with the local council in the community. These local councils are elected by community and it is respectful and expected that you engage with local councils

use strengths-based approaches that privilege Indigenous voices in decision-making processes. This means you start by looking at what is already working well and build from that strength, rather than coming in with a deficit mindset (or looking to “fix” something)

don’t have fixed deadlines: collaborative work in communities take time. You need to build relationships with people first and then be prepared to work flexibly with them. The funding body gave us 12 months initially to complete the project, but it ended up taking about three and a half years from project planning with community to final completion.