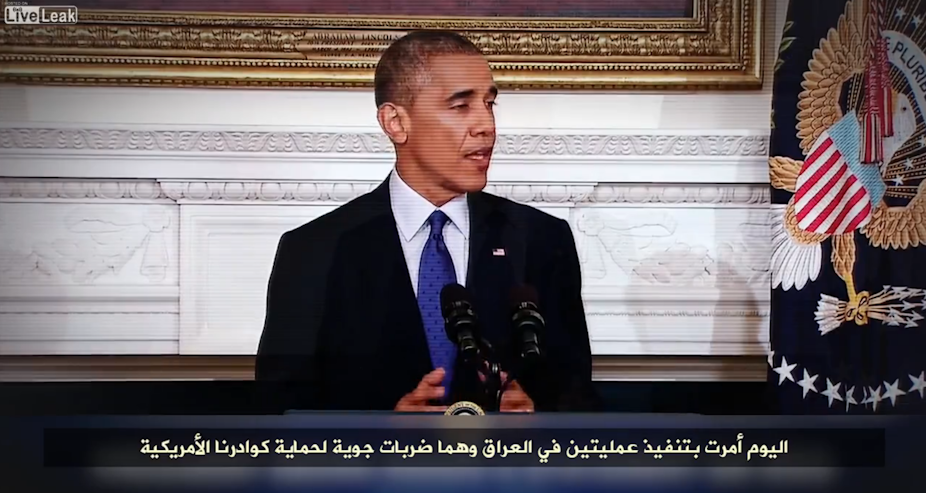

The US government has confirmed the veracity of a video showing the beheading of American journalist James Foley by Islamic State (IS) militants. US president Barack Obama condemned the act overnight, saying that IS:

… has no ideology of any value to human beings. Their ideology is bankrupt.

Meanwhile, a storm has erupted after some newspapers, including the New York Post and Sydney’s Daily Telegraph, used graphic images of Foley about to be executed on their respective front pages.

The Conversation spoke with Monash University terrorism expert Greg Barton to make sense of the act and the responses to it.

What reaction was IS aiming to provoke by releasing this video? What is their strategy?

The first thing to recognise is that IS is media-savvy and that includes social media, and it appears that this awful video – which was technically quite well put together – was very deliberately staged and released. There is a sense with all of the young men fighting with IS of a “Lord of the Flies” mentality on the ground: that people are operating in a zone where they are licensed to kill and commit acts of barbarism that they wouldn’t dream of at home.

But I don’t think what we’re seeing with this video is some random violence – it is a very deliberate bit of messaging. I think the messaging is designed to do two things. One is to provoke an angry response from publics in western democracies: it’s in English, it’s addressed to president Obama, it’s targeting western democracies.

I think there’s the hope that it might put pressure on leaders like Obama and British prime minister David Cameron to increase their military engagement in Iraq and Syria, and that IS feels that that would help them make their case to the people currently supporting the Sunni leaders in Iraq and the Sunni minorities in Syria that the west is against them and they should join with IS.

I think there’s also a calculation that by setting off a firestorm in western media and social media circles, it will feed into a climate of anxiety about Islam and Muslims in a way that makes young Muslim men seeing this happen be even more susceptible to the message that the west is against Islam; there’s a war against Islam and Muslims – and that really there is no choice but to join with those fighting on the other side, with Islamic State.

Is this an example of terrorism as a magnification of limited power?

It’s generally the case with terrorist groups that when they are doing deliberate messaging, it’s done to provoke, because their power ultimately depends on the response they can provoke. Their immediate power is limited; they increase their power with provocation and a response.

With IS at the moment holding so much territory, they actually have real military power on the ground. But even so, they are a movement very much driven by – or supported by – foreign fighters, and therefore very much driven by the need to recruit young men around the world to their cause.

That old mechanism of provoking an angry response and then benefiting from that response still applies. We saw this most dramatically with 9/11. It was intended to provoke a response that would send troops into Afghanistan and as a “bonus” that was probably not expected, getting the war in Iraq, which has led to the current situation we face today with Islamic State. I think we’re still seeing primarily a dynamic of provocation so that the group benefits from the response beyond what they can do directly themselves.

How should social and news media treat acts like these? Should they be more wary?

I think they need to be very wary, given that we are dealing with a group that is trying to provoke an angry response. The last thing we want to do is give them what they want. We have to be very cautious about feeding irrational fears of Islam and Muslims in a way that reifies the message that this group is trying to propagate.

We have seen some quite wise responses, quite spontaneously, to the Foley video. We seen the “don’t re-send this video” movement, a Twitter-led movement, to encourage people to not forward the images on. We’ve see the understandable anger at newspapers perhaps going too far with still images not necessary for the purposes of communication. I think it’s appropriate that the public is responding and saying that’s not right.

We’ve seen a very cautious response and measured responses from Obama and Cameron, and I think it shows we have learnt a few things about the danger of being provoked by terrorist groups.

However, our weakness is that we haven’t been active in the social media space with positive messaging. So for a young person looking at social media trying to figure what’s what, they hear very strident black-and-white voices, very charismatic messaging from groups aligned with IS. But they don’t hear much in response explaining why perhaps they should be more sceptical about the plans made by IS and more questioning of their brutality.

I think we now recognise we have to pay attention to social media. Up until recently, state and federal police weren’t investing in social media in a big way, certainly on this front. We need to pay attention to it both in terms of intelligence but also in actively sending a counter narrative. That will require working with younger people with some religious and community authority – not simply with the imams and the sheikhs that are limited in their ability to penetrate through to the generation that is being targeted by IS.