One of the big attractions at the Melbourne International Film Festival this year is Frank Pavich’s documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013). The film retells the story of cult Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s failed attempt to adapt Frank Herbert’s science-fiction novel Dune – as well as explaining what became of the project afterwards.

Director of acid western El Topo (1970) and avant-garde tale The Holy Mountain (1973), Jodorowsky acquired the rights to adapt Dune in 1974. Through the sheer power of his personal charisma, he assembled an impressive team to work on the film.

Mick Jagger, Orson Welles and Salvador Dali were cast in key roles. Pink Floyd agreed to provide the soundtrack. A team of “up and coming” young creatives – including illustrators Chris Foss and Jean “Mœbius” Giraud, artist H.R. Giger, and special effects supervisor Dan O’Bannon — were hired to produce conceptual art. Their efforts resulted in a phonebook-sized collection of images, reverently referred to in Pavich’s documentary as “the Dune book”.

In keeping with the sensibilities of his earlier work, Jodorowsky saw Dune as a chance to bring 1970s avant-garde ideas to mainstream audiences. Herbert’s original novel concerns a noble family who regain political power by controlling the sole supply of a vital resource — the “spice” — that induces second sight, prescience and ancestral memory in humans who consume it. Although he hadn’t actually read the book, Jodorowsky felt an affinity with these themes of psychic awakening; they meshed well with the Surrealistic sensibilities of his earlier work.

By adapting Dune, Jodorowsky’s ambition was no less than to utilise the full expressive power of cinema to induce transcendent experiences in the audience’s own minds: an acid trip without the acid.

Predictably, Jodorowsky’s vision didn’t impress the moneymen in Hollywood. They deemed Dune unmarketable. When asked about the film’s total run-time, Jodorowsky told producers that it would come in at around 12 to 20 hours. This left the pre-production team to expend their talents elsewhere: Giger, Mœbius and O’Bannon famously went on to make Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979), clearly drawing upon the ideas they developed while working on the Dune project.

Jodorowsky’s Dune is an entertaining story about a group of talented people who tried, and failed, to push Hollywood cinema towards more avant-garde themes. It is perhaps ironic, then, that Pavich’s film is a rather conventional affair. The film consists mostly of talking heads and exhibits little of the aesthetic ambition of its subject matter. Its story of the failed Dune project conforms to a predictable narrative arc of rising action, climax and dénouement.

In short, except for a few occasions where the artworks by Foss, Giger and Mœbius achieve cut-through by the sheer force of their beauty, there are no transcendent experiences to be had while watching Jodorowsky’s Dune. Perhaps Pavich took the lesson of the failed Dune project too greatly to heart.

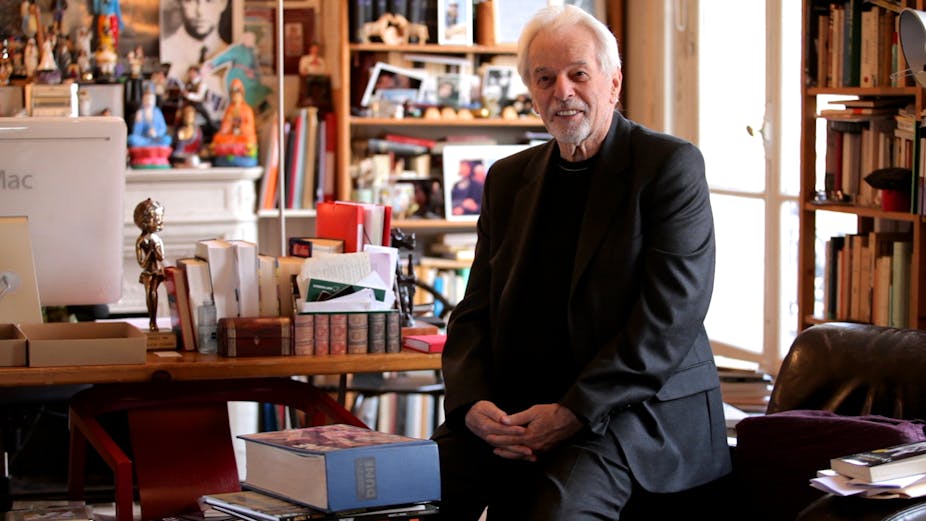

Any lack of creative daring in the documentary is happily ameliorated by its star, Alejandro Jodorowsky himself. He is clearly a man who can spin a ripping yarn, and it doesn’t take long to see why Pavich just lets him talk.

Jodorowsky’s retelling captures the giddy feeling of embarking on a big creative project. When Jodorowsky recounts how he convinced Orson Welles to perform the role of bad-guy Baron Harkonnen, it indeed seems that Dune was fated to succeed. (Jodorowsky did so by offering to hire Welles’ favourite Parisian chef to cook meals on set every night.)

It is quite appropriate that these anecdotes should take precedence in the documentary. Jodorowsky’s innate storytelling capacity is clearly what got people interested in the first place.

Pavich’s film concludes by arguing that Jodorowsky’s project did in fact change cinema because it influenced half-a-dozen other movies. While it is easy to agree that the concept art for Dune inspired films like Alien and Masters of the Universe (Gary Goddard, 1987), the stronger point of Jodorowsky’s Dune is, I think, that unrealised ideas have their own beauty. The Dune project was never a film, but it was a set of gleaming pictures and ideas dreamed up in the minds of its creators.

The point is not merely that inspiration can arise from failure. It is that the pitch can be as poetic as the movie.

The Melbourne International Film Festival 2014 runs until Sunday August 17. See all MIFF 2014 coverage on The Conversation here.