UPDATE: Tim Storrier has won the 2012 Archibald prize for his self-portrait, The histrionic wayfarer (after Bosch).

Shortly after noon today, Steven Lowy, president of the trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, will stand at a microphone in a very crowded gallery and, after thanking the commercial sponsors for their continuing support, will announce the annual raft of prizes.

There will be be dutiful applause (and some surprise – because there always is surprise) when the Sulman, Wynne and trustees’ watercolour prizes are announced, but the mood will change when it comes to the Archibald Prize for portraiture.

The room will tense; journalists, photographers and cameramen get ready to either swivel to a picture on the wall behind the president (the one the staff thought most likely), or to be the first one to sprint to the surprise winner if it’s an outsider.

I have been present at most of the Archibald announcements for the last 40 years. For the first four of those years I worked for the gallery as the most junior curator, so my job was to manage the process. I was standing next to Wendy Sharpe when she was announced as the winner in 1996 and still remember her looking like stunned rabbit caught in spotlight as the photographers and television people ran towards her. It was not a pretty sight.

A brief history of the Archibald

Nor is the prize’s history entirely pretty.

When William Dobell won the prize in 1943 and dissenting artists took the Trustees to court, Howard Hinton later claimed he had meant to vote for another painting. He didn’t make the complaint until he was attacked in the media for his support for Dobell, but it was easier to bring in an impartial authority than argue the toss. The portrait of Joshua Smith so flavoured the prize that a generation later people were still calling it the “Dobell prize”.

The court case against the Dobell decision started another grand old Archibald tradition of contesting the judges’ decisions in courts of law. Mostly the litigants are unsuccessful, but in 1975 the awarding of the prize to John Bloomfield for a portrait based on a photograph was overturned. That was because the conditions then stated that the portrait had to be painted “from life”.

As J.F. Archibald’s will simply stated, the prize was for “the best portrait, preferentially of some man or woman distinguished in art, letters, science or politics, painted by an artist resident in Australia during the twelve months preceding the date fixed by the trustees for sending in the pictures”, it was easy to change that requirement.

An awkward inheritance

The Dobell case may have made the prize a popular festival, but it has not always been appreciated by those running the gallery. When I was working at the gallery as a junior curator, the prize was widely regarded as an embarrassment.

The gallery had been lumbered with a bequest as a result of the will of Jules Francois Archibald (born “John Feltham” but the man loved France), and the media and public persisted in coming to see the results. It was the one time of year the general public was interested in what happened in the hallowed halls of art, and their presence was merely tolerated.

Since then, the gallery has come to terms with its curious inheritance and re-badged it as both a marketing opportunity to gain new audiences and a significant revenue raiser.

In 1975, the gallery instituted an entry fee for artists of $2 to cover the cost of packing and handling each entry. That is now $30. Free entry to the exhibition has become a charge of $10. Commercial sponsorship supplements Archibald’s (now) modest bequest so that the winner gets $75,000, and thus there is always a sprinkling of serious artists hoping to win the lottery.

The nature of the judging means that every entry has to be regarded as a lottery ticket. The real prize is having a work hung. This year there were 839 entries. In less than a day these were culled to 41. Those odds are over 20:1 which means that most artists are incurable optimists. The culling process is swift and brutal.

In Archibald’s day most of the trustees were artists, which is why he made them the judges. Now they are mainly business people with two artists and one art publisher. There have been complaints about the trustees judging art, but because the purpose of the prize is in essence an exercise in social history, the Archibald prize provides an annual chance for mere mortals to gain a relatively easy insight into the way some of the most influential people in the state see the world around them.

The 2012 finalists

This year most of the successful entries are of people in the arts. There isn’t a politician in sight, and the only really economically powerful presence is Paul Newton’s mild-mannered portrait of David Gonski, a former President of Trustees.

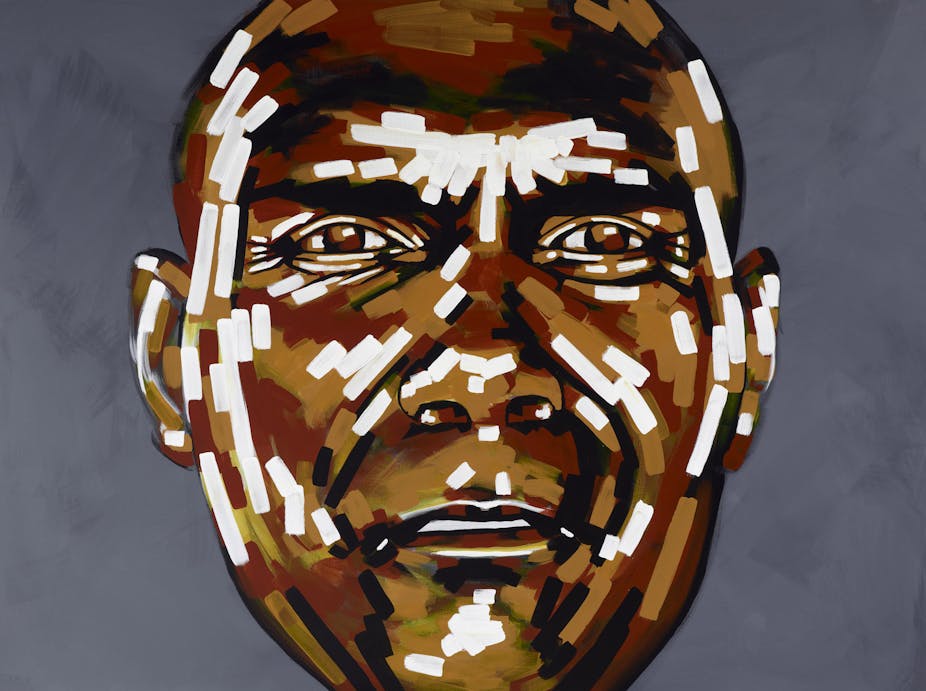

The other change this year is the significant presence of portraits of (and some by) Aboriginal people. Vernon Ah Kee has painted Lex Wotton; Reko Rennie, Hetti Perkins; Luke Roberts, Richard Bell; Martin Sharp, David Gulpilil. There are a number of portraits of visual artists, including some self-portraits. Other art forms do well with actors, singers, and Adam Chang’s portrait of Oscar winning Emile Sherman.

An Australian phenomenon

The growing Aboriginal presence is a reminder that Archibald, the founding editor of The Bulletin, wanted above all to create a body of work to change a culture. He knew that in the early years of the 20th century Australians thought that both history and personal success was something that happened in England.

Archibald left his money for a portrait prize so that many portraits would be painted and succeeding generations of Australians would know what their forebears looked like. Every time I go to the National Portrait Gallery I see works that have been entered (and sometimes hung) in previous Archibald Prizes, and know that he would be proud to see this part of his legacy.

Another condition was that the artist be resident in Australia. Archibald was bitterly disappointed that promising Australian artists, including John Longstaff and George Lambert, had decamped to England. The prize was to bring them home, and its presence was a factor in their eventual return. In the 1990s, Sidney Nolan withdrew his entry at the last minute after it was pointed out that he was no longer an Australian resident.

Finally, Archibald was interested in topicality. The painting must be painted in the previous 12 months. This is where it can get complicated as some works can take a long time to complete. This may be the case with Martin Sharp’s The Thousand Dollar Bill, a portrait of David Gulpilil. It has the same title and same composition as a work completed in 2006 and exhibited in the Ivan Dougherty Gallery, but Sharp is famous for never finishing any of his paintings.

I will be at the announcement this afternoon, as I have been to so many before. I wouldn’t miss it. The Archibald really is the best show in town.