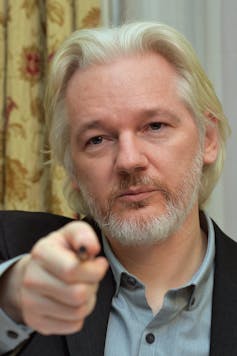

In a tweet acknowledging his award of the 2011 Sydney Peace Medal, Julian Assange thanked the awards committee’s “recognition of my effort in greater transparency and accountability of governments”. In less than 140 characters, he placed himself squarely within the social responsibility theory of the press.

His receipt on behalf of WikiLeaks of the Walkley Award for the most outstanding contribution to journalism that same year confirmed his place in the pantheon. He may be a new kind of journalist, but he is an investigative muckraker par excellence, practising the journalism of commitment, if not the detached objectivity that is sadly losing its place in the news sections of our print and broadcast media.

For this reason, the news that Sweden’s highest court has just thrown out Assange’s appeal against the 2010 arrest warrant that led him to seek asylum three years ago in Ecuador’s London embassy is another dark milestone in the fight for the public’s right to know. Assange remains confined to the embassy.

Who today stands with the young Turks?

In the 1970s, the now late and lamented American journalist, academic and Pulitzer Prize-winner John Hohenberg saw the emergence of “crusading young journalists” as a part of “enormous changes” in the news media firmament. In the work of investigative journalists like Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein (the young Turks at The Washington Post who broke the Watergate scandal and Nixon’s presidency with it), Hohenberg saw welcome evidence of journalism’s expanding influence in the United States.

Hohenberg’s motto was “Go with what you’ve got”. That’s what Assange has been doing, publishing material that impinges directly on the public interest worldwide. Our most esteemed newspaper have co-published his findings with great fanfare. Though some journalists scoff, regarding his success as an affront to their journalistic independence and expertise, others recognise a fellow traveller.

I’m proud that a fellow Australian should be shaking up our sclerotic liberal democracies with a stiff dose of investigative journalism. The risible efforts of various jaded retainers of our craft to somehow belittle or upbraid this brave man for daring to challenge the power of armies and governments will be so much dust on the wheels of the history that Assange keeps making.

Australian journalists today face a malign and unprecedented threat from the Abbott government’s new data retention laws. These laws, among other things, threaten to destroy journalists’ capacity to protect whistle-blowers and other sources who dare to speak for the public interest in open government.

How ironic it will be if Assange ever end ups in an American jail, for he represents a postmodern avatar of one of their own journalistic icons. Before social responsibility theory, the Americans gave the world the “muckrakers”. As David Protess perceptively observes:

most journalists are reformers, not revolutionaries.

Assange has always walked the fine line between the two. Protess notes that at the heart of investigative reporting is “the journalism of outrage”, a genre he describes as:

a vehicle for fulfilling the social obligations of modern media … the journalism of outrage is a form of storytelling that probes the boundaries of America’s civic conscience … Investigative journalists intend to provoke outrage in their reports of malfeasance.

Assange’s ability to outrage and, in doing so, grab the global agenda for the issues that matter to him deserves praise, not brickbats. One expects naysayers to warn of the dangers posed by too much liberty and openness, as US President Theodore Roosevelt did when he castigated early 20th-century muckrakers. But it’s not something you’d expect from any journalist worth their salt.

“He’s not a journalist, not one of us,” they may say. Well, I reckon he is.

Swedish court ups the ante

The integrity of the legal process, in which the charges have kept changing, will be debated for years. In the meantime, one avenue of compromise and hope seems to have been extinguished by the Swedish court’s latest ruling.

The outlook for the 43-year old founder of Wikileaks is grim. Since June 2012 he has been cooped up in Ecuador’s embassy in London, unable to leave for fear of arrest and possible extradition to the United States, whose military and political establishment he has so provoked.

Now the Swedish Supreme Court judges have upped the ante, although one of the five was ready to drop the case.

The questions now are profound, deeply human ones. How long can he last, clinging to his freedom in a protected, but no doubt sorely restricting confinement?

Is this idealist, this early 21st-century muckracker, fighting a losing battle? Or will he yet again, like a contemporary Scarlet Pimpernel, defy those who would apprehend and silence him once and for all?