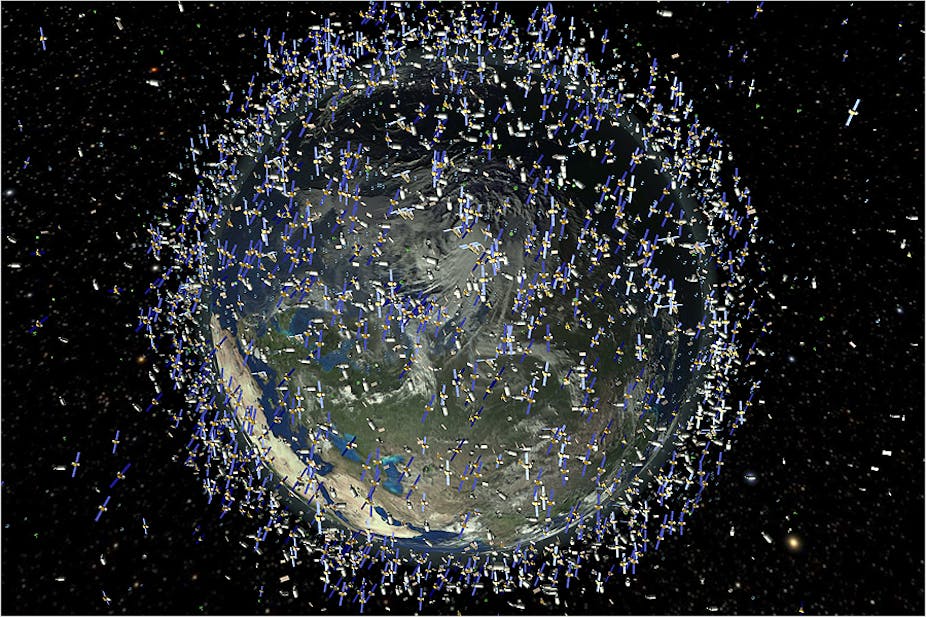

It is said that what goes up must come down. But in the almost 60 years since the first rocket carried a payload into space – the Sputnik satellite in 1957 – there have been hundreds of rocket launches and space shuttle missions that have left behind spent rocket stages, jettisoned equipment and other debris floating in orbit. While some of this does indeed “come down” and burn-up in the atmosphere, much of it is still there – posing a risk to future missions.

What’s needed is some kind of space litter-picker to clean up the estimated 7,000 tonnes of junk whizzing around the Earth. Our RemoveDebris mission, set to launch in 2017, will test equipment and techniques to tackle the growing space debris problem. It can be seen at the Royal Society summer science exhibition in London.

The problem is that this space junk is enormously varied, from dead satellites the size of a car to tiny flecks of paint – even something this small can be a danger to spacecraft when both are travelling towards each other at thousands of miles per hour. At those speeds fragments of only a millimetre across can damage the satellites we rely on for Earth observation, disaster monitoring and communications or navigation.

A piece of junk the size of a grapefruit could completely destroy a satellite, and even cause irreparable damage to the International Space Station. While the ISS has metal shielding to provide some protection, it sports hundreds of dents from smaller impacts and regularly has to move out of the way of larger items flying past.

There are an estimated 170m pieces smaller than 1cm wide, but the largest single item of space junk is the European Space Agency’s 8.5-tonne, ten-metre-long satellite, Envisat. You wouldn’t want to be in the way of that when it rockets past at thousands of miles per hour.

Never mind the Vogons

My colleagues and I at the Surrey Space Centre, alongside teams from our international partners at Airbus Defence and Space, Surrey Satellite Technology Limited, Innovative Solutions in Space, CSEM, Inria, and Stellenbosch University in South Africa, have designed several techniques for cleaning up space junk that will be tested during the RemoveDebris mission.

One will be to catch space debris using a net. Once captured, the pieces can then be dragged behind a spacecraft and burnt up in the atmosphere as it returns to Earth. The largest pieces that survived would fall into the oceans, far away from inhabited areas. To test whether this would work, the RemoveDebris spacecraft will eject a small metal cube (actually a small satellite called CubeSat), which will inflate a balloon to create a larger target. The five-metre-wide net is made of a high strength fibre and includes winches at the end that draw the net closed around the target when it is captured.

Another technique to be tested is the concept of a dragsail, which is a very thin membrane that unfolds into a square sail. One will be attached to the main spacecraft we’re launching. The idea is that when a satellite reaches the end of its life, the dragsail is deployed from a stored position. Just as a sail on a boat at sea is pushed by the wind, the dragsail is pushed by the constant stream of light from the sun, made up of photons. The force generated by this stream is sufficient to drag the debris out of its orbit and cause it to spiral back towards Earth’s atmosphere where it will burn up or drop into the ocean.

Please keep this orbit tidy

If we don’t tackle this orbital litter problem now, within the decade it will cause us major problems. Certain orbits around the planet that are commonly used for satellite imaging, disaster monitoring and weather observation are quickly filling up with old or broken equipment.

There have already been collisions: in 2009 the Iridium 33 and Kosmos 225 satellites collided at a speed of 26,000 mph, adding another 1,000 orbital fragments to deal with.

With enough speeding junk in orbit it could even become impossible to plot a safe path through it, making it too dangerous to leave Earth’s atmosphere – think of the sort of chain reaction seen the film Gravity. This could put an end to space exploration for a generation.

International bodies have been slow to take steps to tackle the problem, and only in the last several years have regulations aimed at reducing the amount of debris left in space come into force. For example, French law requires that the physical components of future space missions within Earth orbit must return to Earth within 25 years. Some other space agencies also abide by these rules, some see them as “advisory”, while others ignore them.

In contrast, the first US satellite in space, Vanguard I which launched in 1958, is still in orbit – and is expected to remain there for 240 years. So there’s much work to do yet.