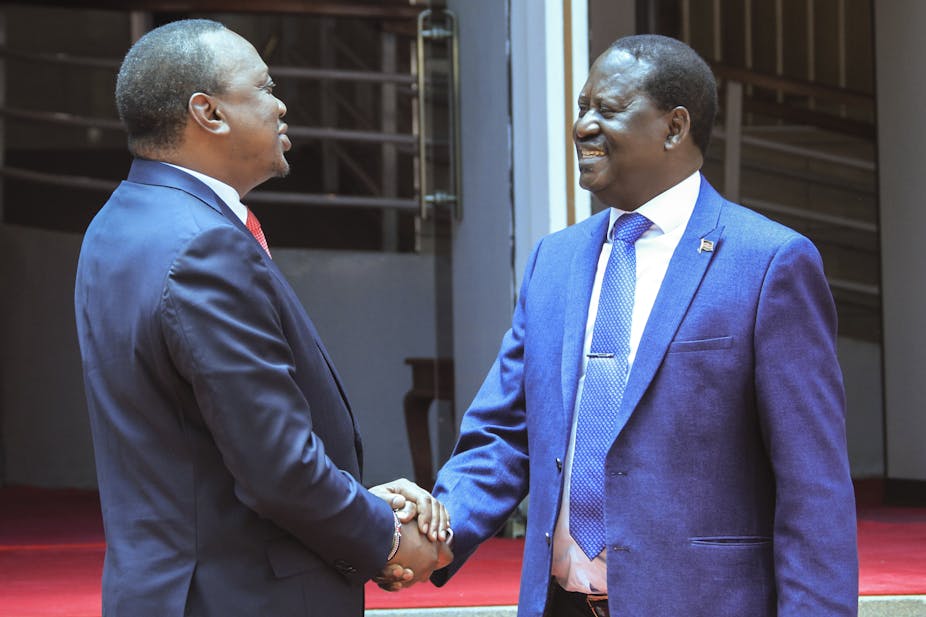

In his state of the nation address to parliament last week Uhuru Kenyatta made a rare personal apology for Kenya’s roughneck election campaign. Cheered by both sides of the House, he urged support for the national reconciliation he and opposition rival Raila Odinga have championed since a pubic show of unity in March. Julius Maina asks Gabrielle Lynch about the hotly debated questions.

What is the context in which Kenyatta and Raila closed ranks?

Kenyatta and Odinga’s handshake on 9 March 2018 came in the wake of a protracted dispute over Kenya’s 2017 elections. Following the polls last August, opposition leader, Odinga, and the National Super Alliance (NASA) successfully petitioned Kenyatta’s re-election. But they then boycotted a fresh election in October on the basis that the election would simply be stolen once again. This decision was understandable, but it left Kenyatta to win in October with 98.3% of the votes cast.

But the fact that turnout fell from 79.5% of registered voters in August to 38.8 % ensured that the October polls failed to resolve the dispute. The turnout didn’t entirely discredit Kenyatta, but it was too low to give him the legitimacy he sought. And it reinforced a conviction among opposition supporters that - as in 2007 and 2013 - the 2017 presidential election had been stolen from Odinga.

In this context, NASA rejected Kenyatta’s re-election and announced the formation of a National Resistance Movement, an economic boycott and plans to form People’s Assemblies. At the end of January 2018, Odinga was unofficially sworn-in as the “People’s President”.

At the same time, the economy took a hit with many struggling even more than usual to buy food and pay bills and fees.

*What are their declared goals and to what extent do they enjoy public support? *

Amid this ongoing crisis, Kenyatta and Odinga held a meeting on 9 March, shook hands and issued a statement on

building bridges to a new Kenyan nation.

This statement set out a number of issues they said needed to be addressed. These included ethnic antagonism and competition, the need to include all communities in governance and development, security and the problem of divisive elections. The stated objective was to build a strong and united nation. But there was very little detail on how this would be achieved.

Since then, Odinga was invited to speak at the country’s annual devolution conference and a team of 14 advisors was announced to steer national dialogue .

Most recently, Kenyatta used his state of the nation address to apologise to any Kenyans he had hurt and to call for reconciliation. Critically, he clarified that, by reconciliation, he did not mean agreement on all matters, but constructive and respectful disagreement and debate.

The vast majority of Kenyans appear to support these goals: stability, security, inclusive development and an ability to speak and be heard are the very things that most people crave. But many are sceptical. This is not the first time that an election crisis in Kenya has ended with a handshake and people are waiting to see what “building bridges” means in practice.

While the majority appear to be happy that the immediate crisis has come to an end and the economy can begin to recover, many fear that this is an elite pact that has more to do with coalition politics ahead of 2022 than it does with ordinary Kenyans.

A significant number of opposition supporters also clearly feel betrayed. In reaching this deal, Odinga seems to have gone behind the backs of his NASA partners. NASA’s commitment to fight injustice also raised hopes that change would be forced through. For some, this hope has turned to frustration and anger, which currently has no obvious outlet.

Who is to blame for Kenya’s recurring dance with death?

The blame for Kenya’s divisive ethnic politics is often placed squarely at the door of the country’s political elite. This is not without reason. Politicians tend to mobilise support among their own ethnic groups and against the assumed spokesmen of other ethnic groups. They have also sometimes incited hatred and organised violence.

But it’s too simplistic to just blame the country’s political elite.

Discussions of blame should start with a history in which a violent and unpredictable colonial state was inherited largely unchanged by a post-colonial elite until a new constitution was passed in 2010. It is a history that has encouraged the emergence of ethnic strongmen and fostered a sense that one is more likely to gain if one of “your own” is elected.

The flip side is to fear exclusion and marginalisation if a collective quest for political power is unsuccessful.

What are the chances of Kenyatta and Raila achieving success?

It depends on what you mean by success and for whom. The pact between them has helped to dampen a confrontational political mood. It has paved the way for other displays of reconciliation. It may also lead to a more concerted commitment to devolution, and to some more investment in opposition areas, as Kenyatta becomes increasingly concerned with his legacy. But it’s too early to tell what this means for political realignments ahead of 2022.

More importantly, such an elite pact can’t change Kenya’s political culture, further strengthen the country’s institutions, or address the deep rooted sense of injustice and marginalisation that many Kenyans share. Success on those fronts requires time and a complex mix of concerted political will, substantive political and economic change, and new popular expectations of the political elite.

On the other hand, failure to address a sense of marginalisation will ensure that the memories of 2017 fuel a sense of a biased and violent state, and of injustice for many. It is thus understandable that many are sceptical. It’s also important that pressure is brought to bear to ensure that promising words are followed by action.