Shocking news stories, such as the conviction of two 12-year-old boys for a fatal machete attack in Wolverhampton, have fuelled worries of an “epidemic” of knife crime in England and Wales. A new survey of 2,000 young people found that nearly half are worried about knife crime. In their campaigns for the forthcoming election, both Labour and the Conservatives have promised to take action on knife possession and violent crime.

Knife crime appears to buck the trend of an overall decline in crime in recent years. Although England and Wales are still among the safest countries in the world, knife crime has shown a clear increase since 2012.

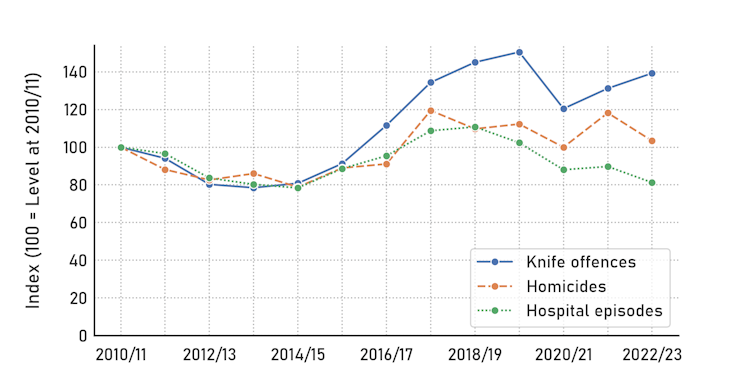

Knife offences, homicides and hospital episodes, compared to 2010-11 levels:

Knife crime is more likely to be reported than less serious offences, and so recorded crime data provides a meaningful measure. It shows that there were around 50,000 knife-related crimes in the year to March 2023, 7% fewer than the pre-pandemic peak. That peak, however, represented a pronounced increase over the preceding seven years. Between 2012-13 and 2019-20, knife offences increased by around 85%.

We can also examine data on hospital admissions, which reflect the serious consequences of knife crime. These also increased from 2014-15 to 2018-19, though to a lesser degree than recorded crime.

More importantly, though, the number declined before the pandemic, and that fall has continued. This could suggest a reduction in the seriousness of individual incidents (more knife crimes but fewer hospital admissions) or changes in recording patterns (less serious incidents being counted as knife crime).

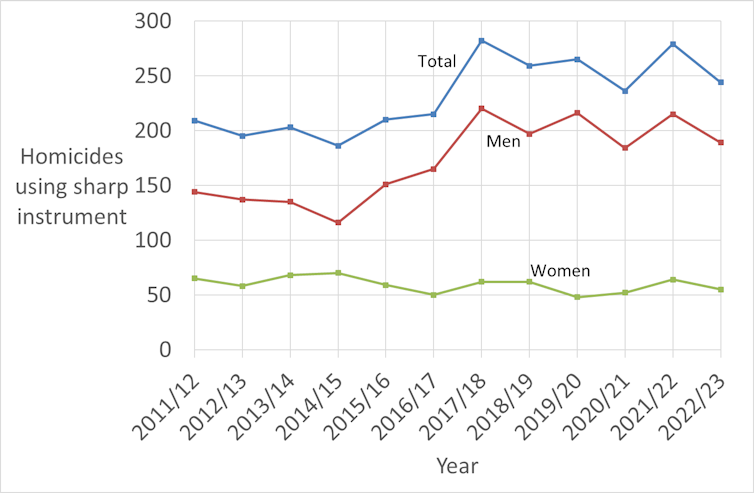

Homicides using a sharp instrument, England and Wales:

In the five years to 2022, knife-related murders (homicides involving a knife or other sharp instrument) decreased 13% from the 2017 peak of 282. Homicide data is reliable because such incidents seldom go unreported.

There are more than twice as many male as female victims, and males account for most of the variation: the number of female victims has declined steadily for many years.

What’s behind the rise?

Some claim that the rise in knife crime is due to government policies of austerity, and others that it is a result of cuts to policing.

We are sceptical of both these explanations. There is no clear mechanism by which austerity would increase knife crime specifically, when most other types of violence and property crime have continued to decline.

And robust reviews of knife crime strategies have failed to find clear evidence of successful approaches. So it is not clear how additional resources would have an effect.

A more likely explanation is the illicit drugs market, which has become more competitive and more violent in the last decade. Increased global cocaine production and trafficking means that, while UK border forces are intercepting more than ever, more cocaine reached the street in the decade before the pandemic compared to preceding years.

This period also saw significant evolution in domestic drug markets, including the emergence of ‘county lines’, with strong links to gang violence and knife crime.

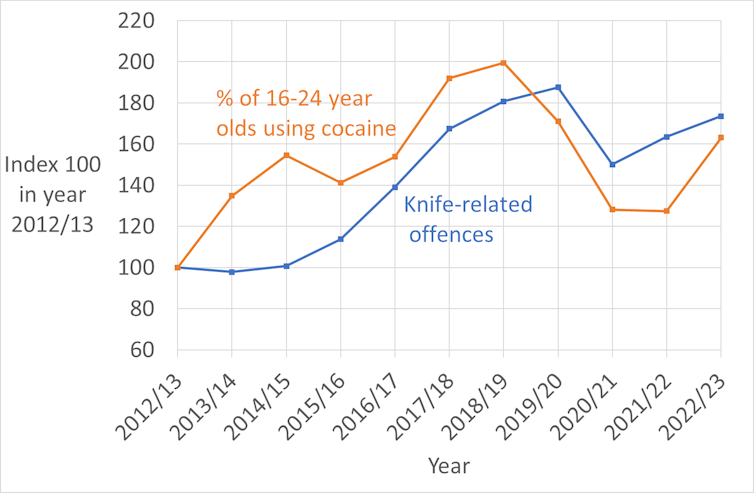

Cocaine consumption by 16- to 24-year-olds in England and Wales increased 90% between 2012 and 2019. The trend is similar to that in recorded knife crime.

Police-recorded knife crime and percent of young adults (aged 16-24) using cocaine in the last year:

Additionally, the proportion of total murders where the victim was using or dealing drugs increased from 50% to 75% from 2016 to 2018 when knife murders surged.

Reducing knife crime opportunities

Efforts to prevent knife crime over the last 20 years have included a mixture of legal measures, like the Offensive Weapons Act, and law enforcement initiatives such as targeted operations to take knives off streets. More recent policies have focussed on a ‘public health’ approach, designed to tackle root causes: the most high-profile example is the creation of 18 Violence Reduction Units in England and Wales, at a cost of £35 million.

The Conservatives have promised in their manifesto to give police more powers to seize knives, and introduce tougher sentences for knife crime. Labour has also indicated it will act to prevent knife possession and violent crime.

But what is most needed are policies to make knives less easily available. If dangerous knives were unavailable, there is not a “next best” alternative weapon that does similar damage as easily.

A key cause of increased knife crime is almost certainly their easy access via online sales. Competitive online markets make knife purchase cheap and easy with little friction: buying in-person requires knowledge, travel time and effort to locate the shop.

Online retailers also need to take responsibility if their sales are causing violence and death. Since 2016 there has been a voluntary agreement among retailers, designed to restrict knife sales to over-18s and limit access to display knives.

But it is not enough and it masks variation. eBay, for example, does not sell any knives except cutlery but dangerous knives are widely available from many popular online shops.

The lesson to be learned from the long-term declines in other types of crime is that opportunity is central. Property crime declined as homes and vehicles became more secure. The same principle applies to knife crime – policy should focus on restricting access to knives, especially dangerous knives, as it has to guns.

The proroguing of parliament for the general election left the criminal justice bill unpassed. It would have banned the manufacture, sale, purchase and possession of “status knives” (like combat and zombie knives that give the carrier more social kudos) and machetes. These or similar measures should be introduced by the next government as these knives appear disproportionately in serious violence.

Yet kitchen knives still account for most knife murders. Kitchen knives with rounded tips should be promoted, and pointed knives restricted.

Other measures, including knife bins (to promote safe disposal) and knife arches (strategically-located detectors) could discourage and thwart knife-carrying more generally. We would expect knife-related crime to decline as the prevalence of knife carrying declined – and this could have beneficial knock-on effects including making illicit drug distribution less violent.

Most forms of violence have declined enormously over the last 30 years, which means we should not consider knife crime intractable.