Lee Rigby’s sister stated in The Sun that Facebook had “blood on their hands” over her brother’s murder in May 2013, following the publication of a report by the Intelligence and Security Committee. The report states that one of Lee Rigby’s murderers discussed his plans to “kill a soldier” on social media five months before the murder, but the security services were unaware. Facebook was criticised for not reporting this to the authorities.

Presenting Facebook as blameworthy focuses media attention away from the fact that many mistakes were made by intelligence agencies and police. Some judgements might be easier than others and Facebook is hardly equipped to evaluate.

Listen to us

But this is all really an attempt to justify even greater extension of government access to social media data. Back in June 2013 The Guardian reported that in the UK, “Mastering the Internet” enables British intelligence agency GCHQ to access “phone calls, the content of email messages, entries on Facebook and the history of any internet user’s access to websites” with a warrant. There are also loopholes which mean that, without an additional warrant, GCHQ may be able to access content of chat between two British people if it was routed via Facebook outside the UK.

Facebook said it already censors and closes pages that discuss terrorist acts to prevent their pages enabling terrorist planning. However, while British surveillance capabilities are already extensive it was bemoaned that UK security agencies had “considerable difficulty” accessing content from companies under US juristiction as they require an American warrant. The report confirms this. The security services in Britain have a reciprocal relationship with the US that goes back to World War I and II. Both countries consider each other as top allies, especially when it comes to counter-terrorism activities and it therefore seems highly unlikely that such a warrant would not be forthcoming.

In defence, Britain tries to complement the US in ensuring its capabilities add value for this important ally. The changes proposed by Cameron would give Britain greater freedom and range of capabilities. In working on a forthcoming book, I have found some evidence of a reciprocal relationship existing in propaganda and information operations.

In interview, for example, Joel Harding, former US Special forces, former director of the Information Operations Institute and current director of the National Security Enterprise Information Strategy Centre, confirmed:

Both the US and the UK can take advantage of one another’s laws to skirt around restrictions, legal and otherwise. If the UK could not do something with a UK citizen, for instance, the US can assist. I’m especially thinking of extremists. That could be a repugnant situation, however, as we honestly think of you guys as family. At least I do, as do most veterans.

But as a former intelligence officer I’ve used that relationship a few times … especially when I was working in Special Operations. ‘Nuff said.

It’s important not to forget the two governments are fighting a broader propaganda war when considering the attacks on Facebook in which they wish to maintain an advantage. The Islamic State (IS) is also currently on a propaganda offensive and hoping its videos will provoke an Anglo-American response that they can manipulate to drive their recruitment.

Dirty tricks

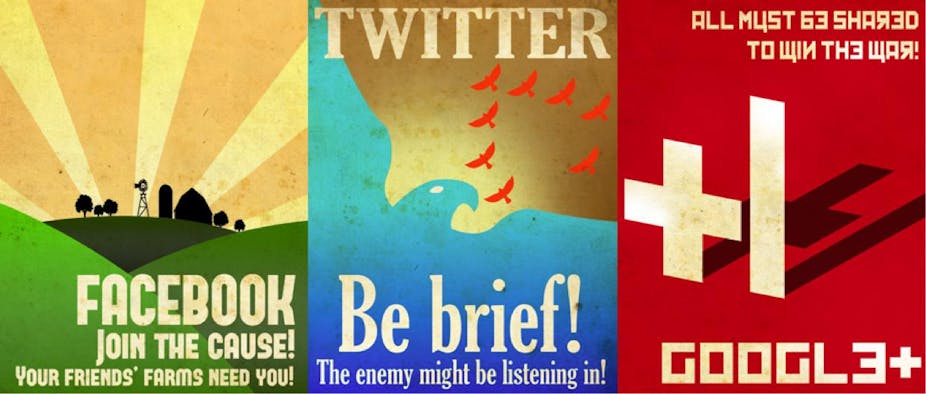

In the online world, GCHQ is also moving toward a greater “offensive” role. With “Squeaky Dolphin” for example it is “crafting messaging campaigns to go viral” using Twitter, YouTube, Flickr, and Facebook. Throughout history security services have attempted to use reporters to spread propaganda and act as spies. This is now moving into social media.

In the US, Facebook, along with AOL, Google and other US companies have been campaigning for an act to, among other things, prevent government access to their customers’ data “without proper legal process” and introduce more controls there. The British government’s attacks on Facebook and statements about their “moral duty” follow a week when the US Senate voted to end discussion of what has been called the USA Freedom Act.

My research shows that many US government personnel saw their own laws governing the internet as too restrictive, particularly when it came to targeting within their own borders. Some pointed to what they saw as an advantage in what were seen as more UK permissive rules, believing these added “value” to their partnership.

David Cameron now seeks to expand the already extensive ability of Britain’s security services to monitor and intercept online content and it is unsurprising that the recent report is being used as a way to shift our focus and build legitimacy for this. Particularly as the US government is fighting the greater restriction of its own access to users’ online content.