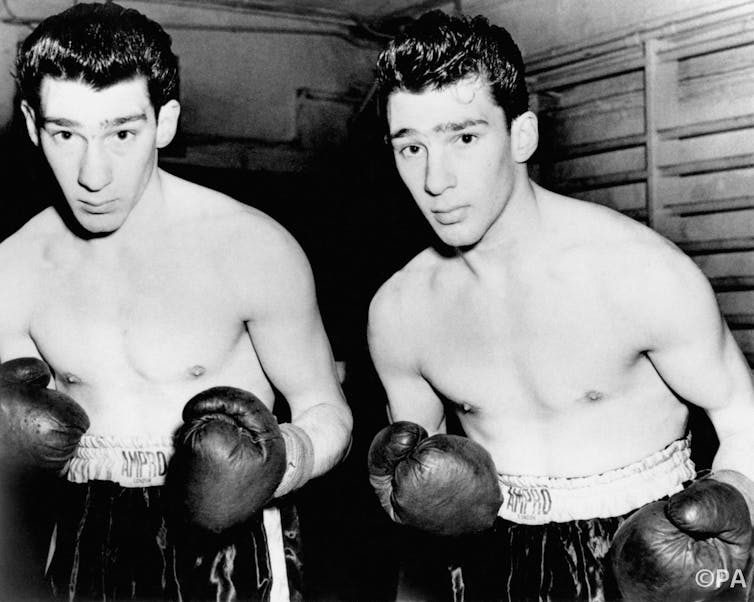

In the very first line of Legend, the new Kray twins film starring Tom Hardy (and Tom Hardy), we hear that everyone in the East End has a story about the Krays and that therefore separating the truth from the lies is rarely straightforward. Yes, Legend is a highly appropriate title for the film.

The enduring fascination of the story of the Kray twins may well be down to its ability to twist and turn. It is frequently retold and reinterpreted as a metaphor for a host of wider social, political and cultural debates that have raged since Ronnie and Reggie ran their extortion rackets in the early 1960s. Legend is no different – casting more light on current social concerns than those of 50 years ago.

Of course, all the clichés are here – the “boys” sharply dressed, associated with (and becoming themselves) minor celebrities, kind to their mother and good to their neighbours. But unlike many previous fictional accounts this film explicitly addresses the stories, the narratives, and the folklore surrounding the Krays.

Entrepreneur or gangster?

This folklore is recast in order to shine particular light on to the blurred line between legitimate business and disreputable criminality, something of particular pertinence in the aftermath of the banking crisis. The film also speaks of contemporary concerns about corruption among political and social elites and celebrity culture.

Some of these themes are fairly well established in relation to the Krays. Fictional and academic studies have viewed the organised crime of the Kray twins and their contemporaries (most notably the Richardsons, their south London rivals) as entrepreneurial firms that developed among sections of the working class during a period of enhanced social mobility and post-war consumerism.

In Legend, it is through the relationship between the brothers that this viewpoint comes to the fore. The tension between them is central to the film mostly because it acts as a thinly-veiled metaphor for a wider tension between the yearning for respectability and legitimate entrepreneurialism on the one hand (Reggie) and the enjoyment and celebration of extreme violence and gangsterism on the other (Ronnie).

This slots in nicely to another branch of study related to the twins: their fraternal relationship. Research into twins is a staple of psychology, criminology and behaviourism. And so the Krays – violent criminals both, but one psychopathic – have provided considerable scope for analysis among both expert and amateur pundits.

Where violence sits

When he first meets Frankie (his future wife and our narrator), Legend’s Reggie describes himself as an entrepreneur and nightclub owner: never a gangster. Later in their relationship Frankie issues various ultimatums, threatening to leave if he continues in crime. Similarly, one of the Krays’ gang – Leslie Payne – runs their business activity and tries to oppose any rash violence that might endanger their considerable income generation.

Ronnie, on the other hand, proudly celebrates his identity as a gangster and relishes opportunities for violence for its own sake. The film portrays Ronnie as someone for whom the opportunity for a shoot-out is always welcomed. A couple of times he bemoans the paucity of opportunities for violence available to him.

So how do the scales balance?

Just as in Tarantino movies and many computer games, violence is celebrated in Legend. Although presented in brutal terms, the many fight scenes in the film are underscored by music – and are staged, choreographed and filmed in ways that celebrate the spectacle of violence. In one important scene, a highly violent fight is presented in graphic terms but is also played for comedy value in a way reminiscent of the slapstick brutality of the Dangerous Brothers portrayed by Ade Edmonson and Rik Mayall. Indeed, there’s a lot of comedy in the film – especially from Ronnie. Contemporary concerns about such celebration of violence don’t seem to have much traction with the filmmakers.

Violence today

However, this portrayal of violence contrasts sharply with one of the few moments of Legend that calls into question the dominant presentation of Reggie as a relatively sympathetic character. His violent domestic abuse of Frankie is presented in very different terms – in silence and with a notable lack of obvious choreography. It is not celebrated, not graphically represented, not played for comedy value.

This is entirely unsurprising, of course. Any other portrayal would be greeted with outrage – and for good reason. But the different ways in which violence is presented in the film reveals much about wider social and cultural attitudes. Domestic violence, which in earlier accounts of the folkloric tales of the Krays featured barely, if at all, is now used to signify the serious moral concerns of the film, whereas the uber violence of gang fights and the streets is presented as entertainment.

So Legend reveals much that is criminologically interesting. Not in the sense that it seeks to explain or document the behaviour of a couple of relatively small-time and relatively unsuccessful gangsters, but rather in what it reveals about current attitudes toward crime and deviance. And crucially, it reminds us that the particular tale of the Kray twins is above all a socially constructed, folkloric narrative account.