“All important movies start with a black screen,” growls Will Arnett over the opening of The Lego Batman Movie, as he breaks the fourth wall to speak to the audience with the same knowing tone which unexpectedly stole the original Lego Movie in 2014. And although this latest outing mines the same seam of pop culture irony – to often hilarious effect – there is a bitter aftertaste: the film also reinforces many of the property’s toxic tropes and legacies.

The pleasure of Batman’s appearance in the original Lego Movie was how successfully the character channelled the essence of the now 78-year-old character into a song. Batman’s self-penned thrash metal cacophony, Untitled Self Portrait, was a brutal skewering of the character with the lyrics: “Darkness, dead parents, continued darkness,” perfectly capturing the latent adolescence of his alter ego Bruce Wayne.

The real surprise of the new film is how much it attempts to explore this arrested development. But in doing so it celebrates the bleakest of Batman source materials: Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns.

Featuring a Batman staring down the barrel of retirement, Miller’s bruising 1986 work concludes that Wayne’s vigilante persona has not disempowered the villains he fights but has instead inspired them. This theme is given flesh (or brick) in the new Lego film when Zach Galafianakis’ Joker bursts into tears because Batman refuses to acknowledge him as his arch enemy. “You mean nothing to me, no-one does,” Batman spits at the blubbing clown prince of crime – who then spends the next 90 minutes attempting to win back the hero’s gaze in ever escalating ways. This is a brilliant lampooning of Miller’s concept but the problem with ultimately using this source material for a family film is that The Dark Knight Returns does not end with Wayne reaching any form of enlightenment.

To Miller, the only thing that means anything to Wayne is Batman. This leads to a highly problematic climax when, rather than be re-integrated into lawful society, Wayne instead goes further underground and forms a private army of child soldiers. Miller’s piece has been attacked by critics as a fascist parable and one of the the biggest shocks of The Lego Batman Movie is seeing how its climax equally celebrates the character eschewing normality. Instead he settles down with a new surrogate family who enable his dark disease. The fact that they all wear batsuits together provides a chilling echo to Miller’s story and the troubling nods it contains to the cult of personality.

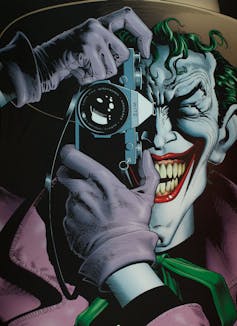

The Killing Joke

Two years after Miller’s Dark Knight Returns, acclaimed British writer Alan Moore examined the depraved dynamics of the Batman/Joker relationship in a storyline whose single gunshot echoed around DC for decades to come. In 1988’s The Killing Joke the Joker is depicted as so desperate for attention that he disables Batgirl Barbara Gordon and forces her father into viewing photographs of her naked, broken body. This brutal treatment of the character has since become emblematic of the portrayal of female characters in comic books as victims, stereotypes and ciphers. So it makes it all the more dispiriting that the Lego Batman Movie treats its female lead in a similarly reductionist manner.

Thankfully Rosario Dawson’s Gordon is not subjected to the same level of physical humiliation as her comic book namesake. She instead suffers an insidious process of trivialisation which diminishes her status from an empowered Batman rival to an ancillary sidekick. Studies of gendered linguistics have laid bare the suppressive nature of names, typified in this film by Batman’s ceaseless paring down of Gordon’s moniker from Commissioner Gordon to Barbara to “Babs” and finally Batgirl.

And, although the narrative attempts to sideswipe this disenfranchisement with a sly line of dialogue, it is clear that this character’s independent identity has been replaced with that of a supplicant, a process known in comic book circles as “fridging”.

Fans of Harley Quinn - the Belle de Jour of the contemporary comic book - may rightfully complain that her portrayal in the Lego film is tied to an outdated 1990s version of the character. But at least this subordinate representation has precedent. Squeezing a successful adult woman into Batgirl’s juvenile uniform is instead a chauvinistic creation of the filmmakers but one which sadly chimes with the often troubling history of the character.

Toxic behaviours?

But are we reading the piece too much at face value? The point of satire after all is to exaggerate the flaws of the subject in order to puncture the pomposity of the myth. And when the film is at its most lucid, the Lego Batman Movie does this very well. Not even Miller portrayed the wretchedness of Wayne’s life as vividly as the excruciating Lego scene in which he watches a microwave slowly warm up his dinner.

But the film often dangerously indulges the toxic behaviours of its protagonist too. The message of the film to children, that playing together is better than playing alone, may appear innocent enough on paper. But that message appears troubling onscreen when that togetherness involves strong female characters surrendering their status and identity in order to accept sidekick roles.

Sequels typically go darker but here the “Everything is awesome” mantra of the first Lego Movie seems has been swallowed up entirely by that opening black screen.