On the morning of October 16 1964, Harold Wilson entered Downing Street as prime minister. He had just ended 13 years of Conservative rule – one that had been predicted to last a generation just four years previously.

Wilson, many believed, achieved this victory by promising to unlock the talents of all Britons, whatever their class, by unleashing the “white heat of technological change”. The Labour leader claimed his government would achieve this economic and social revolution by using the state to foster market dynamism.

Ed Miliband also hopes to enter Downing Street next year, yet his party has largely ignored the 50th anniversary of Wilson’s 1963 white heat speech and 1964 triumph. It’s true that early 21st century British politics looks very different to its mid-20th century equivalent but Miliband should still take heed of Wilson’s 1964 triumph as he approaches the 2015 general election.

Miliband may be deliberately avoiding comparisons with Wilson because of the former Labour leader’s disappointing performance in office. In the long term, Wilson did indeed struggle to translate his promise of radical change into government policy but his early period as leader proved to be one of Labour’s few historical high points. It was comparable with 1945 and 1997, when the party appeared, if briefly, to evoke a positive response from voters across all the classes.

It’s not the economy, stupid

While Wilson made much of his background as an Oxford-trained economics expert, he failed in particular to convince the public that he would be better at managing the economy than his Conservative rivals. Even though Alec Douglas-Home, the old Etonian aristocrat in charge of the Tories, publicly questioned his own ability to do maths, his party still enjoyed a 13-point lead when the public was asked who was best at managing the economy.

It would only be when Tony Blair became leader that Labour would first take the lead on this issue. Miliband and Ed Balls, his shadow chancellor, currently struggling to convince voters they can be trusted with the economy, might take some comfort in that. Perhaps it doesn’t matter as much as they think on polling day.

Similarly, Miliband might also note that the public had little faith in Labour’s ability to manage immigration but still voted the party to power in 1964.

After the 1958 Notting Hill riots, immigration quickly became a salient political issue for the first time. White sensitivity about unrestricted black Commonwealth immigration – much of which was highly racist in origin – encouraged the Conservative government to impose limits on the numbers of people allowed into the UK. Labour’s response was uncertain. It first rejected, then endorsed this controversial move. Wilson’s tactic was to ignore the issue as much as possible, for fear that even talking about it would hand his rivals an advantage. This appears to be very much Miliband’s line too.

Third party threat

When it came to threats from other political parties, Wilson didn’t have to deal, as does Miliband, with a party like UKIP that successfully exploited fears about immigration. The racist right was tiny and divided in the 1960s. But another group was threatening to take votes from Westminster’s two big parties at the time.

Taking advantage of discontent with Labour and the Conservatives, the Liberals won the Orpington by-election in 1962 and while their leader Jo Grimond was no populist, he still won as many headlines in the early 1960s as Nigel Farage today. Hoping to hold the balance of power, the Liberals stood in an unprecedented number of constituencies in the October election.

But instead of winning seats, the Liberals mostly took votes from the Conservatives. In so doing, they enabled a decisive number of marginal constituency seats to be delivered straight to Labour. Miliband must surely be hoping that UKIP will do the same in 2015.

The past is not a foreign country

No political conjuncture is ever quite the same, but nor is the past an entirely foreign country. Harold Wilson defied many disadvantages to win in 1964 and Miliband should look closely at his much-maligned predecessor’s achievement.

For the two leaders share a similar strategic position. Wilson set out to make himself acceptable to the suburbs while retaining Labour’s traditional working-class support – which is what white heat was all about. Similarly, Miliband needs to win back voters lost in 2010, but keep hold of those who stayed loyal despite the Brown government’s troubles. Wilson’s 1964 victory was a narrow one but he successfully navigated this tricky task. It’s a position Miliband would do well to emulate in 2015.

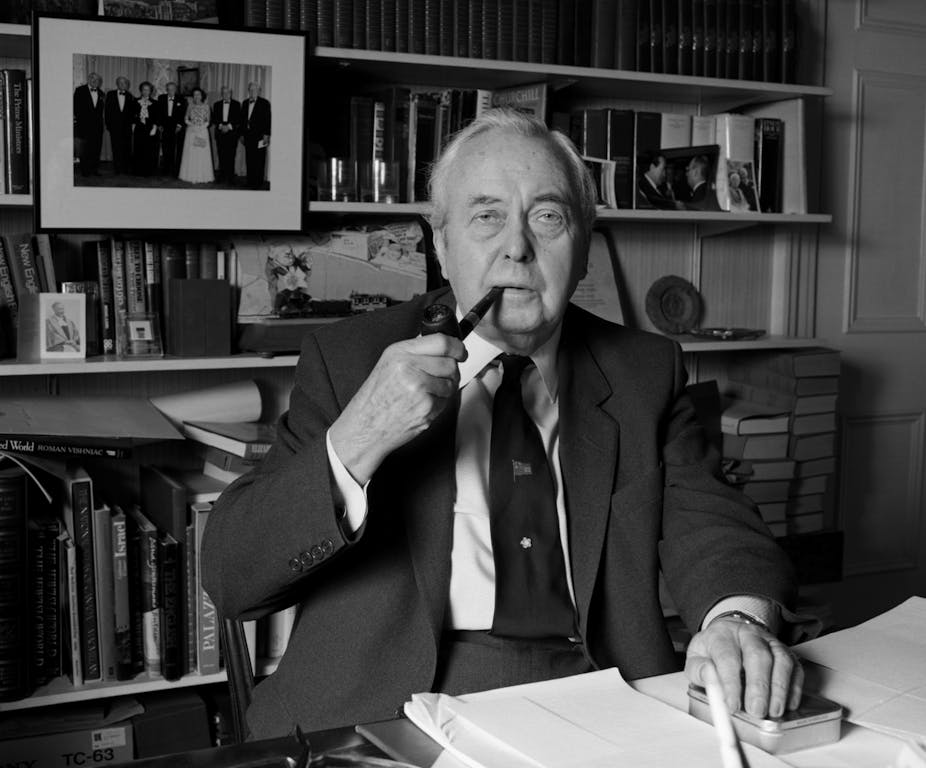

Wilson however was able to do something his successor has not yet done: project a persona that resonated with the public. His pipe, Gannex raincoat and penchant for HP Sauce might have made Wilson a fit subject for satire but it also less-than-subtly gave the impression that, despite his elite education, this grammar school boy was also a man of the people. The contrast with Miliband is stark. Perhaps that is why the current Labour leaders has avoided speaking of the early Harold Wilson – he might suffer from the comparison.