“It all started with a word,” said Polish president Bronislaw Komorowski at the opening of a memorial to freedom of speech, “and the word was ‘freedom’”.

The event completed three days of commemorations in Warsaw of the 25th anniversary of the end of communist rule in Poland. Coincidentally, the elections that came to symbolise freedom for both Poland and the whole former Soviet bloc took place on the same day as the Tiananmen massacre: June 4, 1989.

While the end of communism in Europe is commonly associated with the fall of the Berlin Wall months later, those elections – the first free elections in the Soviet bloc – sealed its fate.

The elections were, arguably, only “semi-free”. The result of negotiations finalised on April 5, 1989, reserved 65% of lower house seats for politicians representing the old order and left only 35% open for newly legalised political parties and independent candidates. Once the election results were announced, Polish society’s desire to change the system was clear: the opposition won all the available lower house seats, and 99 of 100 seats in the newly created senate.

Poland became the first Soviet bloc nation in which opponents of the communist system gained political power in a legal and democratic way. Within Poland, the elections accelerated the transformation to full democracy. More broadly, the vote paved the way for similar events across the Soviet bloc, including the iconic fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, and ultimately the dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991.

In Poland last week this was emphasised by both Komorowski – “we broke the Iron Curtain” – and US president Barack Obama, who said:

We must never forget that the spark for so much of this revolutionary change, this blossoming of hope, was lit by you, the people of Poland.

Until a few months ago, the 25th anniversary was mostly to commemorate a historical milestone, with possible reflections on the future of Poland. Then, just a few days before the event, came the death and funeral of General Wojciech Jaruzelski. He was infamous for implementing martial law in 1981 and jailing Solidarity activists. Later, as a result of the round-table agreement, he became the first president of the post-communist Polish state.

The coincidence of these events revived the many controversies about not only communist rule and the martial law of 1981, but also the political and ideological compromises needed to make the transition to a full democracy without open conflict, blame and punishment. Some old wounds were re-opened, only to be sidelined by the contemporary significance of the 1989 elections.

Lessons of history for Ukraine

Recent events in Ukraine have put the iconic elections in a whole new perspective. They are now a very concrete example to follow, demonstrating that a democratic transition can be achieved through dialogue and negotiations.

The anniversary also was an opportunity for the Polish and American governments to declare support for (and solidarity with) the Ukrainian people, framing them as “heirs to Solidarity”.

It’s no coincidence that the first Solidarity Prize (dubbed the “Polish Peace Nobel”) worth one million euros, of which 700,000 euros is to be spent on programs supporting democracy, was awarded to Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev.

Polish authorities invited new Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko to attend the commemorations (and meet, for the first time, both Obama and US Secretary of State John Kerry). Russian president Vladimir Putin was not among the 50 heads of state present. As the Polish Ministry of Polish Affairs explained:

We only invited allies from the EU and NATO.

The crisis in Ukraine also reminds Polish society – and the world – about the fragility of global power arrangements that provide some sense of security. The new world order is being threatened by Russia’s attempts at expansion, most of it towards the west.

Poland has been a member of NATO since 1999 and the European Union since 2004. Yet today, with armed conflict quickly approaching its eastern border (a mere 300 kilometres from Warsaw), the nation doesn’t feel as secure as only a few months ago.

This is why Obama’s main speech in Warsaw focused more on the future than on the past. His message was one of support for Poland and all other NATO allies in Eastern Europe:

Poland will never stand alone. But not just Poland: Estonia will never stand alone. Latvia will never stand alone. Lithuania will never stand alone. Romania will never stand alone.

Obama recognised Polish scepticism about such promises:

I know that throughout history, the Polish people were abandoned by friends when you needed them most.

But Obama assured: “These are not just words. They’re unbreakable commitments.”

It remains to be seen if the US would act in the case of Russian aggression. France and the UK surely didn’t, despite a trilateral pact, when Nazi troops invaded Poland in 1939. Still, the message to Russia was clear:

We will not accept Russia’s occupation of Crimea or its violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty.

The crisis east of Poland dominated the political dimensions of the commemorations. A legendary figure of Polish anti-communist opposition, Adam Michnik, said:

The presence in Warsaw of the US President … reminds us of the meaning of our Ukrainian neighbours’ fight for identity and freedom, for sovereignty and rule of law.

Michnik was editor-in-chief of Poland’s first free and largest newspaper, Gazeta Wyborcza (Electoral Gazette), which was founded to provide a voice to the opposition during the electoral campaign of 1989.

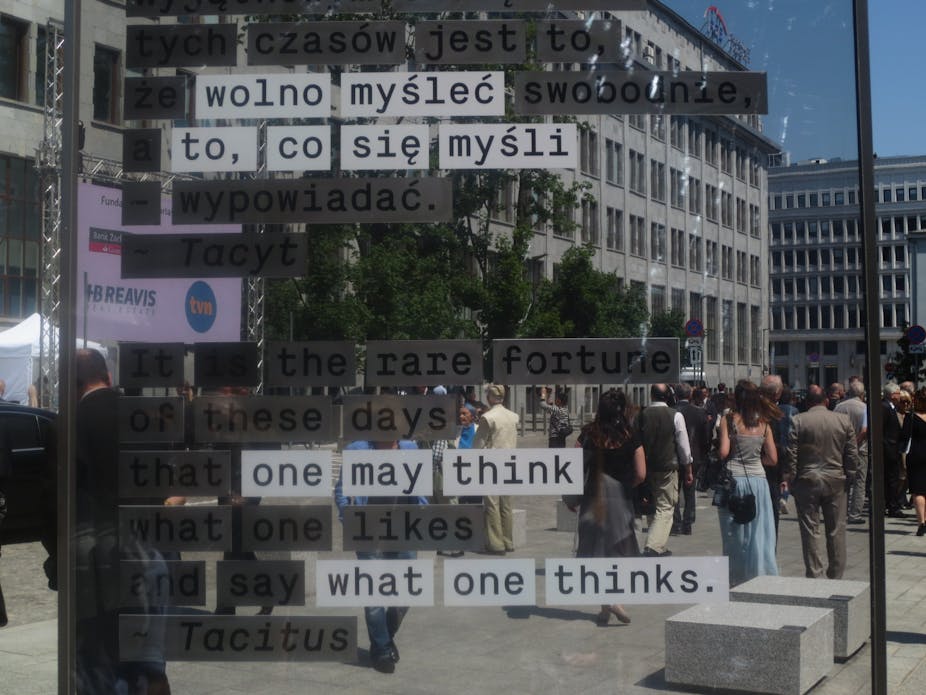

The free press and freedom of expression were central to commemorations of the anniversary. Among the many symbols, comparisons and reflections on this anniversary, the notion of freedom was paramount.