In recent days, news organisations around the world have sought to explain to global audiences both the Voice to Parliament referendum campaign and the result. The picture they have painted of Australia is not exactly flattering. The BBC, for example, described the win for the “no” side coming after a “fraught and often acrid campaign”.

The Washington Post declared it a “crushing blow” for Australia’s First Nations people who “saw the referendum as an opportunity for Australia to turn the page on its colonial and racist past”.

Even the play-it-straight Associated Press declared the rejection of the Voice as a “major setback to the country’s efforts for reconciliation with its First Peoples”. Similarly, Reuters reported on fears the result “could set back reconciliation efforts by years”.

Australia’s own media warned a “no” vote could be seen as evidence that Australia was a “racial rogue nation”. A crucial question, then, is whether this result will affect the way the world views Australia and potentially have an impact on Australia’s international relations.

‘Uncomfortable fault lines’

Much of the world’s attention over the past week has been focused on the Israel-Hamas conflict. Yet, the data we’ve been analysing from Meltwater, a global media monitoring company, showed a 30% increase in mentions of the Voice to Parliament in the mainstream news and social media in the week leading up to the vote. There were 297,000 mentions this past week, compared with 228,000 mentions the preceding week.

Much of this content was generated within Australia, but just before the referendum, there was an uptick in the number of “explainers” produced by global news organisations.

The BBC, for instance, reported the historic vote had

exposed uncomfortable fault lines, and raised questions over Australia’s ability to reckon with its past.

The New York Times wrote the referendum had

surfaced uncomfortable, unsettled questions about Australia’s past, present and future.

A number of pieces compared Australia unfavourably with other settler-colonial nations in terms of the legal recognition of First Nations people, including New Zealand and Canada.

Japan-based Nikkei Asia reported:

Australia is the only developed nation with a colonial history that doesn’t recognise the existence of its Indigenous people in the constitution.

An explainer by Reuters similarly pointed out:

First Nations people in other former British colonies continue to face marginalisation, but some countries have done better in ensuring their rights.

And in an interview with Reuters, the UN’s special rapporteur on the right to development, Surya Deva, said the Voice debate had “exposed the hidden discriminatory attitude” in Australia towards Indigenous peoples.

Misinformation grabs headlines

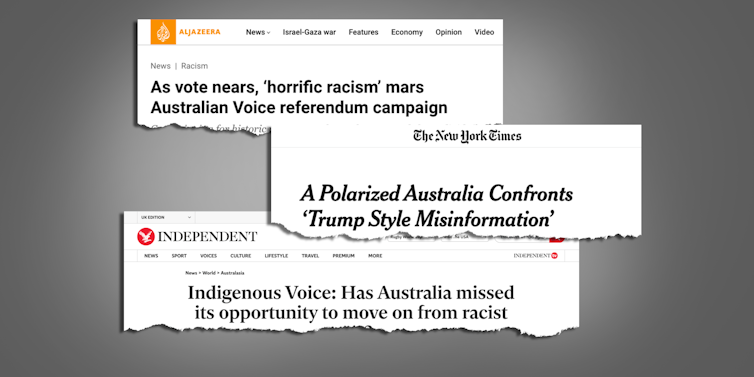

Some international media also pointed to the large amount of misinformation that had surfaced during the campaign.

The New York Times, which had extensive coverage of the campaign, reported the country had become “ensnared in a bitter culture war” based on “Trump-style misinformation” and “election conspiracy theories”.

One blunt BBC headline explicitly linked misinformation to racism: “Voice referendum: Lies fuel racism ahead of Australia’s Indigenous vote”.

A Reuters explainer similarly reported on concerns that “racist and false narratives” had sparked fears the Voice would be a “third chamber of parliament”.

Many outlets had compared the Voice to Parliament referendum to the 2016 presidential election of Donald Trump in the United States and the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom. This referendum result, however, was less surprising and generally reflected the polls.

How will this affect Australia’s relations?

In a previous analysis piece, we wrote that most mentions of the Voice in the international mainstream media and social media had been generated by the United States, followed by the United Kingdom. In the last week of the campaign, there was a 30% increase in number of media mentions of the Voice (9,100) from US traditional news and social media accounts, compared to the preceding week (7,000).

Yet, despite the negative tone of the coverage, it seems unlikely the result will substantially affect Australia’s relations with either country. Concerns about the shifting geopolitics of the Asia-Pacific region have brought the three countries much closer in recent years. This was cemented further by the AUKUS pact.

In the Asia-Pacific region, however, leaders have no doubt been watching the referendum, even if they will not immediately comment on the result.

China’s representatives might be quiet now, but there is little doubt the “no” vote will contribute to the strategic narratives that Beijing uses to blunt Australia’s criticisms of its human rights abuses on the international stage.

A measured interview with Indigenous academic and poet Jeanine Leane in China’s Global Times newspaper, for example, carried the headline “Colonialism, white supremacy loom over Australia’s aboriginal referendum”. This is, however, not entirely out of step with some of the other coverage emerging from Australia’s allies and partners.

Indian security expert Ambika Vishwanath argued in a piece for the Lowy Institute:

it seems extraordinary that a country such as Australia, one that largely aligns itself with ‘Western’ norms and values of freedom and democracy and a liberal outlook on life, has yet to recognise the people that originally inhabited the continent for close to 60,000 years.

New Delhi now has another avenue for pushback if Australia raises concerns about India’s domestic politics.

For some in the Pacific, the result will not come as a surprise. It may entrench views of Australia as a settler-colonial state unwilling to grapple with its past, including colonialism in the Pacific.

As the referendum is a domestic issue, it is unsurprising other governments’ leaders have not immediately commented publicly on the result. But this does not mean they’re not watching. The Australian government must now explain to the international community the “substantive policy steps” it is taking to close the gap in Indigenous disadvantage - a tough ask.