No one has ever claimed that the gods of theatre are fair. Musicals have flopped in London for any number of reasons: some were ahead of their times (the first production of Sweeney Todd), some were overpriced (Spring Awakening), and some were just miscast (Ian McShane in The Witches of Eastwick). Of course, there were also those that simply were bad (like Fields of Ambrosia or Viva Forever!).

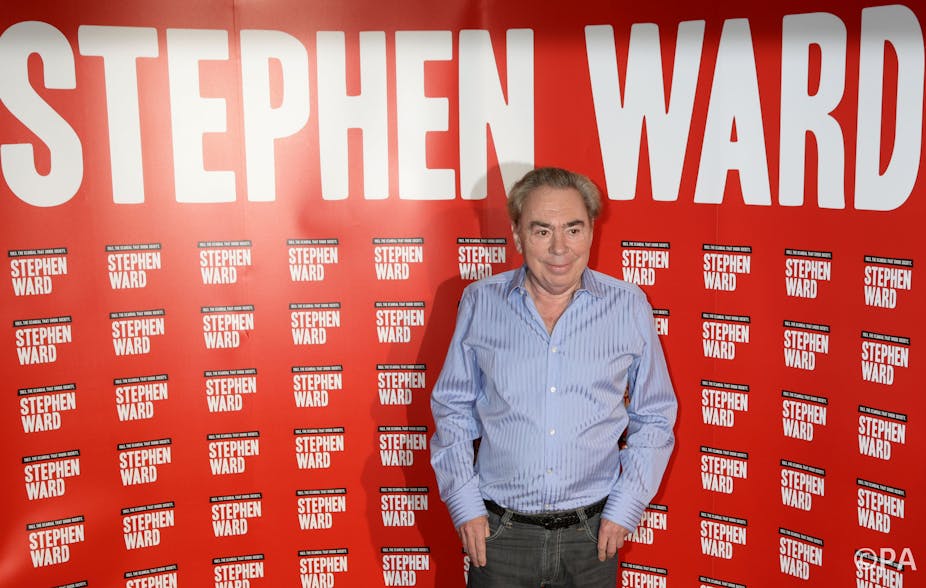

Why then couldn’t Stephen Ward – which closes early on March 29 after a West End run of just four months – find an audience? Routinely referred to as “Andrew Lloyd Webber’s new musical”, the show about the Profumo affair boasted an impressive creative team. Oscar, Tony and Olivier Award-winning artists included Don Black (lyrics), Christopher Hampton (book) and Richard Eyre (direction). These are all supremely talented people, so what went wrong?

To write a show about “osteopath to the stars” Stephen Ward, a key figure in the 1963 Profumo scandal, was an intriguing idea. It was Ward who introduced the then secretary of state for war, John Profumo, to the young Christine Keeler. The minister and the model began an infamous affair which not only ruined Profumo’s political career and brought down the Conservative government. It also resulted in Ward being found guilty of “living off immoral earnings”, (in other words, being a pimp). Before his sentence was announced, Ward committed suicide on August 3 1963, aged 51.

It’s an incredibly dramatic story. But musical theatre is all about working together and following a shared vision – and this was clearly not the case with Stephen Ward. It seems that the collaborators never agreed exactly what kind of show they were aiming for. A sharp satire of the English establishment? A romantic musical about the tragic fall of a well-meaning playboy? A sweeping kaleidoscope of the early 1960s and people’s desperate attempts at (sexual) liberation? A passionate indictment of the hypocrisy of the political system?

It tried to be all of these and thus wound up being nothing in particular. Throughout the evening that I saw it the audience appeared puzzled as to what exactly they were seeing.

The production got off on the wrong foot with its misconceived opening number Human Sacrifice. The song reduced the fascinating fact that Ward wound up as an exhibit in the Chamber of Horrors at Blackpool’s Madame Tussaud’s to a pointless anecdote. Here, as elsewhere in the show, music and lyrics made an awkward fit. The ominous music was more suited to gothic stories like Lloyd Webber’s The Woman in White or The Phantom of the Opera.

Several songs served no real purpose. I’m Hopeless When It Comes to You, sung by Profumo’s wife, Valerie Hobson, was just distracting. Hobson hardly got a look in otherwise in the show and consequently was not a character the audience could care for.

Other scenes went on long after the audience got their – fairly obvious – point. So the police forced small-time criminals to give false testimony? So the court was biased? It’s nothing that hasn’t been seen a hundred times.

The one song that the audience responded to was You Never Had It So Good, which showed the upper classes engaged in a (rather tamely staged) orgy. This is the kind of mockery of the decadent rich that people are familiar with and know how to react to. Musically, the song was clearly modelled on My Fair Lady’s Ascot Gavotte, but at least its lyrics were witty.

The show also ended on a bum note. Ward’s passionate Too Close to the Flame was more bewildering than revealing because the metaphor lacked specificity: what was the flame supposed to stand for – fame, wealth, passion, sex, political influence? None of these putative answers could explain the show’s title character. Ward’s motivation was never satisfyingly established. If Ward didn’t want to have sex with Christine Keeler, why did he chase her? If he didn’t want to blackmail their lovers, why did he insist that Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies tell him all about their affairs? As Ward, the marvellous Alexander Hanson gave a heroic performance, but even he could not illuminate a protagonist who was no more than a cypher.

Surprisingly, Eyre’s direction had no flair; Hampton’s libretto was clumsy, and Black’s lyrics were often out of period and inappropriate to the characters singing them. But in contrast to Lloyd Webber’s last endeavour, Love Never Dies (2010) – where practically the only element that worked was the music – this time it is the composer who must take most of the blame.

As a score, Stephen Ward had no stylistic coherence; a lot of it was no more than glorified recitative. Some of the songs didn’t build, but simply used the same melodic motif over and over. Other compositions were far too emotive for the show’s vivacious, lusting-for-life characters. And Lloyd Webber’s pastiche of late 50s/early 60s pop sounded perfunctory. Just compare the tired Super Duper Hula Hooper to any of the zestful song parodies in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat.

Like its underwhelming score, the musical pulled in various directions, none of them particularly original or interesting. It’s not that 50 years after Profumo’s resignation, the public might no longer be engrossed by the affair or its aftermath. It’s rather that the musical failed to make a convincing case for why it should.