South Australia’s Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission has recommended the state investigate an international storage site for intermediate and high-level (spent fuel) nuclear waste.

This coincides with the shortlisting of South Australia’s Barndioota Station as the federal government’s preferred site for storing domestic low- and intermediate-level nuclear waste.

Two years ago, Barry Brook and I argued that “nuclear waste is safe to store in our suburbs, not just the bush”. Based on the knowable hazard and established management techniques, we argued that storage and even disposal of radioactive materials does not demand the use of the remotest locations Australia has to offer.

Fast forward to today, and our nation, with its well-earned reputation for hypocritical antipathy to nuclear technology, is taking serious steps toward hosting used nuclear fuel from the global market.

So how is our “don’t avoid involving our cities” argument holding up?

As a member of the independent advisory panel assisting the federal government in the siting process for the domestic facility, I have learned a lot about how the waste challenge can both succeed and struggle with the tools available to us.

Getting community buy-in

For the domestic facility, committing to a voluntary process paid dividends, with an unexpectedly high 28 nominations from around the country.

So, lesson one: voluntary processes can work. Give people a no-obligation process and many will participate.

Lesson two: in a voluntary process you work with what is volunteered. I would have loved to explore locations closer to Australia’s capital cities, but none were volunteered, so the point was moot from the get-go.

In assessing these volunteered locations, experts on our panel could say with relatively certainty that nearly all nominated sites were “good enough”. Give or take some design and engineering, they could all work well.

Here lies a perverse problem: Australia is spoiled for choice in terms of technically good locations for such facilities. To distinguish between locations on physical characteristics inevitably favours flatter, drier, remoter locations.

This can have unintended consequences, as remote locations scream “danger” in a perfectly rational way to everyday Australians.

So lesson three: just because we can does not mean we must. The mere availability of somewhere more remote than another place may not make it materially better, even if it looks better in assessment.

So is Barndioota Station a good choice for detailed site assessment and deeper consultation?

In many respects, it is excellent. The location was volunteered by the landowner. It is, technically, outstandingly suitable even by Australian standards. While remote, it has reasonable accessibility.

There are no known cultural heritage issues on the site itself and no native title claim.

The local government has expressed support for a more detailed assessment, as did a notable body of stakeholders in the nearest towns. There is flexibility in where the actual facility (just 100 hectares) could be placed within the very large station property.

Counting against, the traditional owners have expressed their wish for this site not to proceed. Some neighbouring landowners and community members have also expressed concerns.

That holds lesson four: in none of the long-listed locations was support from local stakeholders universal. We must maintain realistic expectations in that regard.

If this sounds like a broadly familiar situation, it is. Back in 2014 we wrote of the (failed) process to shortlist Muckaty Station in the Northern Territory for a nuclear waste site. We asked:

How have we ended up with a process that includes only one site, with that site in the middle of nowhere?

With no disrespect intended to Barndioota Station, we seem to be in roughly the same place today, even if the process that brought us to here was remarkably robust.

I’m feeling the irony. I don’t object to the Barndioota decision per se. However, I suspect that shortlisting only Barndioota may prove to be the catalyst for agitation based on perceptions of unfair imposition. It doesn’t need to end that way, although there is much work ahead.

Now for international waste

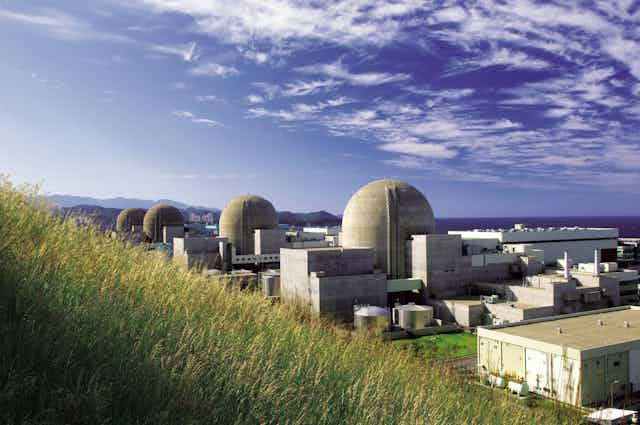

These lessons are crucially important if South Australia goes ahead with a higher-level, international waste site. The commission has proposed a storage site in two stages: a temporary above-ground site, before shifting to a permanent below-ground site over a period of 30 years.

A safe above-ground temporary facility for storing used fuel can go anywhere with suitable zoning.

If the whole state is to profit, then the whole state must be equitably involved in the responsibility. That may not suit an entirely voluntary process.

Keeping our cities involved may demand a more active hand from government in identifying and involving sites, based on the recent experience that wholly voluntary processes may not yield any near-city locations. As a resident of Adelaide, I would welcome an approach that actively included suitable sites near my city.

We also need to walk the talk in demonstrating the difference between hazard and danger.

An adult African lion is hazardous to humans. Yet three of them live in the centre of Adelaide, in our zoo. The hazard is there, yet instead of thinking “danger” we think “outing with the kids”. The difference is the engineered barriers, the operators of the zoo, and the trust we have in these barriers and institutions.

The storage of high-level nuclear waste should be no different. It too should be a site for education, visitation, science, research and development. It should be planned and presented as a part of the future industrial and cultural fabric of our state.

Should South Australia create such a facility I will honour this pledge: give me a crib, some power and an internet connection and I will live there, among the casks, for a week. Or a fortnight, if that will make the difference.

While good science necessarily deals in probabilities, safety is essentially a binary issue for everyday people: it is or it isn’t safe. I say it is, so I will do it.

Australia has moved remarkably quickly in the nuclear space to be now seriously examining a project of global significance, in part thanks to an embrace of innovative ideas and approaches. We mustn’t stop the innovation now.

Ben will be on hand for an author Q&A 5pm AEST Thursday May 12. Leave your questions in the comment field below.