In the lead up to the release next month of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) Fifth Assessment Report we are exploring concepts of confidence and certainty in climate science. You can find the other articles here

“Virtually certain”, “extremely likely”, and “high confidence”: these terms get bandied about in climate science, but what do they really mean? And what do they mean for us?

The previous IPCC report (AR4) from 2007 expressed “very high confidence” that global average temperature increases were very likely due to the observed increases in greenhouse gases concentrations.

Various leaked draft reports suggest that in the imminent fifth assessment, our understanding of the human causes of global warming has strengthened. The leaks suggest the upcoming report could raise that level to “extremely likely” or even “virtually certain”.

In this series we have discussed confidence and likelihood. These are used to communicate the degree of scientific certainty in key findings.

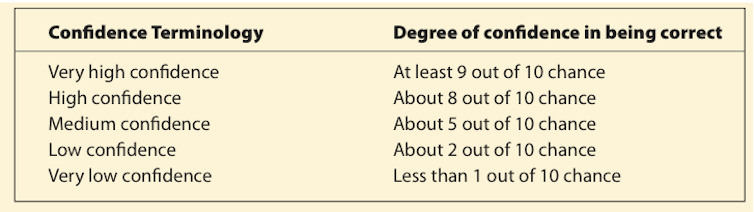

In the IPCC reports, confidence is expressed qualitatively and tells us how certain we are that scientific findings are valid. The level of confidence is determined by the type, amount, quality and consistency of evidence. A “very high confidence” means that there is at least a 9 in 10 chance of a finding being correct.

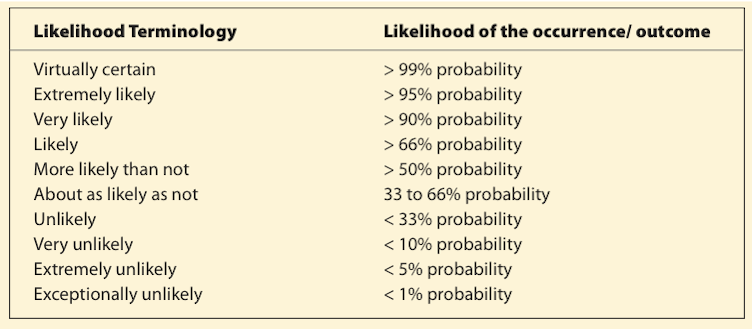

The certainty of scientific findings is then described using likelihoods. Findings are assessed probabilistically using observations, modelling results or expert judgement. They are assigned a term from a scale ranging from exceptionally unlikely (less that 1% probable) to virtually certain (more than 99% probable).

The IPCC uses these scales to convey specific information about our understanding of, and confidence in, scientific findings. Results with low confidence can be framed as such, and are treated as areas that need further investigation. Conversely, scientific findings that are backed up by multiple, consistent and independent lines of high-quality evidence are communicated with high confidence.

It’s understandable that terms like “virtually certain”, “extremely likely” and “very high confidence” create some confusion as to how sure climate scientists are about anthropogenic climate change.

We are “virtually certain”, for example, that there will be an increase in the frequency and severity of extreme high temperatures. At first “virtually certain” might sound unclear. It might sound a little confused, or perhaps that the fundamental science isn’t quite settled yet.

But as we have shown in our previous pieces in this series, the use of the terms “virtually certain” and “extremely likely” illustrates the vast body of consistent scientific evidence around climate change that has been established over the last 150 years.

Often commentators point to remaining uncertainties in our understanding of climate change as a reason to delay on action. But our certainty has been steadily increasing. In 2001, the IPCC concluded that the human influences on the climate were likely (greater than 66% probability) already detectable. This increased to very likely (greater than 90% probability) by the 2007 IPCC report.

This trend is clear. The upcoming report will likely deliver an even stronger statement on the human role in climate change, close to the highest level of certainty we can communicate and reflecting the high level of scientific consensus.

Climate change is clearly a broad, complex problem requiring consideration from scientists, politicians, communities and individuals. But the language employed by the IPCC tells us that human-caused temperature increases is a well-understood theory, comparable to our understanding of gravity.

With this degree of scientific confidence, it’s time to stop suggesting that any remaining scientific uncertainty is what’s holding us back from decisive action on this increasingly urgent matter. With so much at stake, do we really want to bet against these odds?